Chapter 14: Performance-Based Pay

Overview: Describes how to create a pay-for-performance plan, wherein pay increases are based upon performance appraisals.

Corresponding course

INTRODUCTION

A major goal of compensation programs is to motivate employees to perform their best. This goal gained importance in the United States when organizations realized they were in danger of losing markets to foreign competitors. Many programs were launched to elicit employee cooperation and increased effort on the job, to make American products better and more competitive. These programs go under a number of names, such as variable pay, merit pay, alternative pay, incentive systems and pay-for-performance. 1 In this book we will use two of these terms: merit pay and variable pay. Merit pay was introduced in the last chapter. It is arrived at by making base pay increases within pay grades contingent upon performance. The expansion of this topic will be the main focus of this chapter. The next chapter will cover variable pay. This form of pay goes beyond pay increases within the pay grade to set up a different form of pay; a cash incentive based upon a measure of performance.

Pay-for-performance is not ordinarily a complete a salary structure as when paying for the basic job and possible competencies. Instead, paying for performance is integrated within or added to salary structures primarily based upon performance criteria. With merit pay, performance becomes the standard by which the employee moves upward within the pay grade for the job. In most variable pay plans performance is a factor that leads to an addition to base pay or base pay is lowered to make room in the compensation budget for a cash incentive performance reward.

DESIRABILITY

The idea of relating pay to performance is highly attractive to most managers – so much so that almost all organizations claim that they have pay for performance in the form of a merit pay system. But there is a great deal of evidence that pay for performance is not easy to implement, not always desirable, and not as prevalent as the surveys would indicate.

Both management and employees agree that tying pay to performance is desirable. Studies show that managerial employees feel that their level of performance should be the most important variable in establishing the amount of a pay increase.2 While not all groups of employees rank performance that highly, to most employees performance is a significant indicator of how much pay they should receive.

Organizations clearly perceive that pay for performance is important. Most organizations surveyed claim they connect pay with performance in setting pay rates for employees.3 Furthermore, the practice is spreading to more employee groups. Whereas managers have always worked under merit pay systems, the emphasis for other employee groups has usually been equity. But more and more emphasis on performance is extending to nontraditional groups such as teachers.4

Despite its obvious appeal, not all aspects of pay for performance are desirable. First of all, a focus on performance often conflicts with the compensation goal of equity: in a pay-for-performance system, employees in the same work group doing the same work may be earning substantially different pay rates. Feelings of inequity can always arise in this situation, especially if the program is not well designed and communicated or where people do not perceive performance as a proper variable by which to set pay.

A second reason that pay-for-performance may not be desirable stems from the first one. The program implicitly or explicitly puts people in competition with each other. Yet what is needed for the work of the organizational unit to be accomplished is cooperation. Where everyone has to work together, differential pay can have a divisive effect that may produce lower and not higher performance for the group as a whole. This may explain why first-line supervisors are often not as enthusiastic about pay-for-performance as higher-level managers.

A third reason that pay-for-performance may not be desirable is administrative. As will be covered in this chapter, pay-for-performance takes managerial time and effort and must be designed and administered carefully. Failure to put forth the managerial and staff effort required will lead to a program that does not in fact tie pay to performance and will make employees distrust management.

This leads to the fourth and last reason that pay-for-performance may not be desirable, which is lack of trust. Pay-for-performance most often relies on the judgments of managers about the level of performance of employees. Unless employees trust the judgment of the manager and perceive that it is in fact their performance that is being rewarded, there is a good possibility that they will see the program as manipulation of employees by management. The problem is that trust cannot be entirely created by the compensation program. Although a good program can enhance the feeling of trust, it must be present throughout the management process.

PREREQUISITES

A pay-for-performance program requires a compatible organizational situation if it is to succeed. To examine the feasibility of having pay-for- performance, it is useful to review the three components of expectancy theory.

Valence

The first part of expectancy theory says that people must feel that the reward being offered, in this case money, is important in satisfying their needs. Although an argument can be made that money is the most universal instrument for need satisfaction, it is clear that its value to different people is not the same. A pay-for-performance program is going to work best where pay is highly valent to the people covered by it.5 This valence cannot be assumed, it must be determined by research.

As an example, a researcher was called in to a company where a group of women seemed unable to meet production standards despite the attractiveness of the incentives provided. He discovered that this was a group of traditional women who believed they should not make more money than their husbands and felt guilty about not being at home when their children got out of school. The researcher suggested to management that the women be allowed to go home as soon as they had met their standard for the day. The suggestion was accepted and the productivity of the group improved immediately.6 These workers were not completely motivated by money. Lawler suggests that programs such as pay for performance be installed only in units where the employees clearly have a high need for money.7 In circumstances where management wants the motivational force of pay-for-performance, then it is useful to select people who clearly have a need for money.

The Performance-Reward Connection

It should be obvious that for pay-for-performance to work there must be a connection between pay and performance. This is easy to say but very difficult to achieve. Organizations are complex social systems whose members are subject to many influences on their performance at any one time. To isolate a simple connection between pay and performance is not possible. A number of problems increase the complexity of the connection.

First, any compensation program tries to achieve a number of things at the same time, and these goals are not always consistent. Second, even if the program does make the connection, the employees must perceive the connection. Historically, secrecy in pay is a factor that leads employees to guess at this connection, usually inaccurately.8 Organizations are increasingly provided information, education, and training about compensation programs so there is more transparency around pay decreases and financial rewards systems. The connection is not always a comfortable one to employees, who may therefore try to assume it does not exist. Third, pay-for-performance is only as good as the performance appraisal method and how it defines "good" performance. A perception that the performance-appraisal system is biased or does not appraise actual performance destroys the connection for the employee. Performance appraisals will be discussed later in this text.

A serious complication is that management and employees may not agree on the performance level of the latter. Meyer studied a number of occupational groups and found that people tend to rate their performance higher than does management.9 Specifically, he found that over 95 percent of his respondents rated their performance above average; and 68 percent thought they were in the top 25 percent in performance. If we compare such findings with the assumption of pay-for-performance, that performance is a normal distribution, then we can see that a great many employees are not going to perceive that their pay is related to their performance.

The Performance-Effort Connection

Employees must perceive that their effort leads to performance. A pay-for-performance program assumes that performance varies among employees and that this difference is observable. But in many jobs, variation is impossible or is so little that it is unrealistic to try to measure it for pay purposes. Even if there are differences, measuring them or attributing them to the effort of the employee may be difficult. For instance, it may not be possible to divorce the efforts of an individual in a group project from the efforts of the other members of the group. The employee may not feel he or she controls the important measures of performance. Teachers, for example, realize that for them the important measure is student learning, but they feel only minimal control over that variable.

The main point is that pay-for-performance is not a solution for all motivation and performance problems in organizations. It can be very effective where the requirements of expectancy theory can be met. But in many circumstances its application is likely to lead to frustration and other problems within the organization.

DEFINING PERFORMANCE

The first two definitions of performance in the dictionary are: (1) The execution of an action, and (2) something accomplished. In terms of an employee this would suggest that performance has to do with what the employee accomplishes and what actions or behaviors go into creating the accomplishment. From this, performance criteria may fall into three categories: inputs, activities, and outcomes.

Inputs

An input is what the person brings to the job. This includes the employee's knowledge, skills, abilities, and effort. A pay for knowledge plan may define performance as developing or increasing knowledge, skills, or ability, but this plan must specify exactly what is to be learned or improved. Effort is controllable by the employee and may be a good performance factor if it can be measured and known to lead to a desired outcome. (Note the bias toward outcomes in this statement.)

A real problem is when the performance definition is a personal characteristic. It is common to have such factors in performance appraisal. But the employee who is told that he/she rates low on such a factor feels personally attacked and rated down on something that is hard to change at best.

Behaviors

Behaviors focus on what the employee does at the job. They measure the way the job is done. Again, the thought behind this is if the employee does the job correctly, then the desired outcome will occur. The advantage of defining performance as a behavior is that it is more observable than other criteria. Doing the job the way it needs to be done is very important in organizations where work must be coordinated between employees. Some performance appraisal techniques, such as BARS (Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales), focus clearly on this definition of performance.

Outcomes

Outcomes usually come to mind when the word performance is used. Outcomes are the productivity measure of the employee, group, or organization. As an example, in a conversation with the woman who ran the Faculty Club, she said that she had four waiters and one of them could handle more than twice the tables of any of the other three. That one waiter was clearly more productive. Why don’t we just use outcomes as the measure of performance in all cases? There are three reasons:

- Identifying and measuring desired outcomes can be very difficult for many jobs.

- The outcome may be achieved but in ways that are unacceptable. A salesperson who sells a large quantity of goods to a customer with poor credit creates more problems than the value of the sales.

- How one goes about doing the job may also be important. A bank teller who treats customers politely is valuable to the bank, but this is not an outcome of doing the job.

Differential Performance

Differential performance is assumed to occur in organizations. It is usually desired but is also restricted by the way jobs are designed. Assembly-line jobs are often designed so that variation in performance is impossible or irrelevant to the desired outcomes. Variation in performance where tight coordination of activities is necessary creates trouble and does not necessarily increase productivity. On the other hand, jobs such as sales, engineering, and management have a great deal of latitude in their effects on outcomes.

There is also an intermediate position between these two extremes that may be very common in organizations. Most raters can identify those few employees who are doing an outstanding job. Likewise, they can identify those few who are doing very poorly. But most performance-appraisal systems ask that performance distinctions be made among all employees. It is very likely that not only is making distinctions in the middle of the performance scale very difficult, but also that the differences are so small as to not warrant differentiation.

Differential performance is not just an ideal; it is a fact. Some people are capable of producing two or three times what others are, and the best as much as five or six times more than the worst. These findings indicate that the reward system of organizations could create much higher levels of performance and therefore productivity in employees, if it were clear to the employees that they would be rewarded for the increased productivity. But it should be kept in mind that not all jobs permit differences in performance and not all organizations require or desire them.

The preceding comments assume that good performance means higher output. This is certainly an important definition of good performance, but it is not the only one. How the job is done may also be very important. The organization may wish to reward a series of behaviors as well as the productivity of the employee. A focus strictly on the outcomes of work, such as sales volume, allows the organization to pay directly for those outcomes. This type of payment system, a variable system, is the topic of Chapter 16. If the organization wishes to focus on more than just outcomes or finds it difficult to measure the outcomes, then performance appraisal comes into play and the pay-for-performance programs discussed in this chapter are appropriate. The distinction between these two systems can also be likened to that between measurement and appraisal.

PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

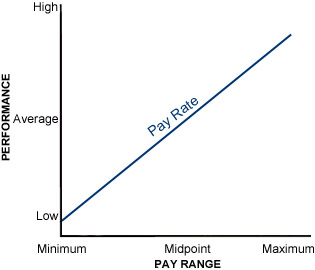

A merit pay system is a particular method for determining the movement of employees within a pay range. The goal of the program is to match employee performance levels with position in the pay range over time. This idea is illustrated in figure 14-1.

Movement upward in the pay range occurs only if the employee's salary is lower in the pay range than his or her performance is on the performance scale. Employees whose salary exceeds their performance standing receive no increase or a lump sum payment. Merit Pay allows the organization to move high performers upward in the pay range very fast by giving large increases to these employees. It also allows movement downward in the pay range if the employee's performance level goes down by freezing the salary at the current level.

A merit pay program requires the use of an open pay range, a good performance appraisal system, and a guide chart for pay increases.

Open Pay Range

A pay-for-performance program relies on an open pay range. (See Chapter 13 for a description.) Such a pay range defines only the minimum, the maximum, and the midpoint of the range. This pay range needs to be broad enough so that it is possible to give large pay increases to good performers. Movement within the pay grade is determined strictly by the performance of the employee, and the position of the employee within the range is maintained only by good performance over time. Having reached a particular point in the range, the employee may slip back the next time the pay structure is adjusted if his or her performance is not as good as in the present period.

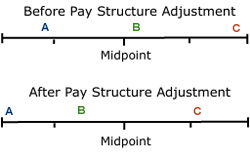

The starting point for determining a pay increase is the position of each employee in the pay range after a pay structure adjustment has been made. This is illustrated in figure 14-2.

In this illustration there are three employees: A, B, and C. Before the structure adjustment, A was between the first and second quartiles, B was just above the midpoint, and C was at the top of the pay grade. After the adjustment A is at the bottom of the pay grade, B is in the second quartile, and C is between the third and fourth quartiles. It is the newly adjusted positions that are the starting points for determining the pay increases for the next period.

Performance-Appraisal Rank

It must be possible to place each employee within a distribution of performance. This distribution is assumed to be divisible into segments such as quartiles, and each individual can be identified as being within a particular segment. This system does not allow for everyone being rated high or low; it assumes that there is an even spread of performance – a normal distribution. If this distribution does not appear in the ratings, spreading out the ratings along the continuum will develop it.

Guide Chart

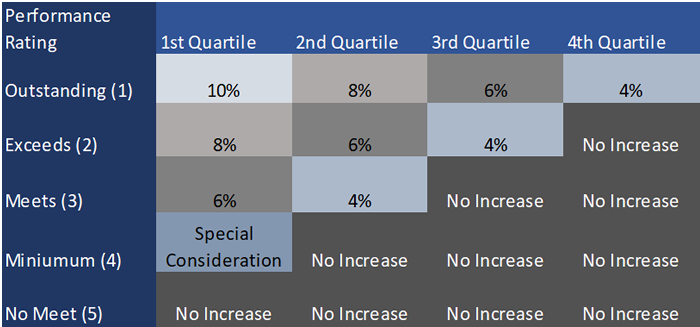

Pay range and performance rank are combined in a guide chart, as illustrated in figure 14-3. This may also be referred to as a merit matrix.

The horizontal dimension of this chart is the present position of an employee in the pay range. The vertical dimension is the performance ranking of the employee. Each employee can be placed in a box on the guide chart if these two dimensions are known about them.

The boxes in a guide chart indicate the appropriate percentage of increase that should be given to any employee in the current period. The amounts are determined by the budgetary process and the amount of adjustment that has been made in the salary structure. As an example, suppose that the salary structure adjustment illustrated in figure 14-2 was 4 percent. If employee C's performance during the period just ended was outstanding, then we would want to move his/her salary again to the top of the pay range, a 4 percent increase. If B's performance was below average, no increase would be called for. Finally, if A's performance was outstanding, then a maximum increase should be granted: 10 percent according to figure 14-3. Note that even this increase would probably not fully equate A's salary with his/her current performance. A continued high level of performance would lead to larger increases and a matching of performance rating and position in the pay range. In general, then, employees whose combination of salary and performance places them on the left upper portion of figure 14-3 will receive above-average increases, while those in the lower-right areas will receive small increases or no increase.

The example in figure 14-3 is a simple one: it varies only the amount of the pay increase with performance and the place in the pay range. Rather than having a set percentage increase, as illustrated here, each of the boxes could have a range, say 9 to 12 percent, so that finer adjustments could be made for those close to the boundaries of the boxes. Even more movement for good performers and less for poor performers can be allowed by altering the time period between adjustments, such as giving increases to good performers every six months while granting lower performers increases every eighteen months. Such alterations allow the top percentages to not appear so large and the percentages at the bottom to appear larger than they really are.

Operational Considerations

The ability of a merit pay program to connect performance and reward is a function of the design and administration of the performance appraisal system of the organization. The rest of this chapter discusses the design of performance appraisal systems, but there are a couple of other points that need to be made about the operation of performance appraisal in conjunction with pay increases.

A merit pay program puts a lot of pressure on the supervisors doing the appraisals. Doing performance appraisal makes supervisors uncomfortable. They often feel like they are "playing god". 10 In addition, the employees know that pay is a direct outcome of this evaluation and put as much pressure as possible on supervisors to receive a positive rating. In other words, performance appraisal puts the supervisor's employees in a competitive position, while the supervisor is trying to obtain cooperation and coordination. This leads supervisors to attempt to ameliorate the harshest effects of the system. An alternative being used more and more is performance management, a process that focuses on continous development, coaching and mentoring instead of a single, year-end event.

One other issue with annual appraisals was described to the authors by a Human Resources Director. The flow was supposed to be from performance appraisal to pay adjustment, not the opposite. This Human Resource Director noted that the first time the program was put into operation, there was a large discrepancy between performance and place in the pay range; the best performers were not necessarily the highest paid. The second time around, the discrepancy had almost disappeared, a much greater change than the initial adjustments would have accounted for. Further examination showed that the second time around, the supervisors made out their performance appraisals with an eye on where the person was presently locatd in the pay range. This situation was particularly bad, since many of the top performers were women, whose pay was toward the bottom of the pay range, and by neglecting to utilize their current performance their pay was not properly accelerated.

Merit Pay Budgets

In order for the merit pay process to operate there must be a budget. This merit pay budget has two aspects:

- Determining the size of the budget

- Allocating the budget to organizational units in the organization

Budget Size. Each year, as part of their budgetary process, organizations review their compensation budget to determine how much to allocate to the merit pay plan. There are a number of factors that go into determining the size of this budget item. They include:

- The organization's financial situation

- Cost of living changes

- Industry and geographic changes estimated for the next year

- Retention and turnover rates within the organization

- Organization policy on pay levels.

There are a wide variety of salary budget surveys available. Salary increase surveys forecast competitive salary increase rates by industry, location, and job function. One solution, ERI's Salary Assessor has a screen/tab that calculates how different salary increase percentages might impact the organization’s bottom line.

With this accumulation of information, the organization makes a decision about how much of a merit budget to finance for the coming year. This figure is stated as a percentage of the current payroll.

This budget is then allocated to organizational units, usually as a percentage of each unit’s payroll. While this method is easy, it may not reflect differences in organizational unit performance. A flexible allocation system establishes performance standards for organizational units that allocate more or less to units, depending upon their overall performance.11

A basic problem with merit pay is that the salary increase budgets of organizations have typically been very small. This means that average performers receive raises that often do not keep up with the cost of living, while good performers' increases are not significantly different from other employees or the cost of living. These factors reduce the motivational potential of the merit pay program.

One way to get around this problem is to make changes in the Pay Form that will be discussed more in Chapter 18. In this instance, it would involve changing the pay level decision for base pay to lower than the market and placing the added amount into the merit pay budget. The overall pay level would not be affected, but individual pay would be affected either positively or negatively depending upon the performance of the employee.

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION METHODS

Evaluating performance is a necessary organizational process that takes place naturally in the act of managing. For certain purposes, this process must be standardized. That is, the way in which it is to be done should be specified and the results of the process recorded in such a way that employees can be compared with one another.12 Performance evaluation is an integral part of the Human Resource program of an organization. As such, it has several of functions. These functions are not necessarily congruent with one another, so there is a great deal of trouble in developing performance evaluation systems that are equally useful for all purposes to which organizations wish to put them. In particular, there is a constant tension between the employee feedback and behavior-change goals on the one hand and the Human Resource system goals (such as merit-pay increases) on the other hand.

Measurement of Performance

First it is necessary to distinguish between the measurement of performance and the appraisal of performance.13 Variable pay plans [Chapter 16] pay employees for actual results, as compared with expected results. Hence, they require determination of expected results (called production standards) and methods of measuring actual results. Traditionally, in manufacturing industries, the development of production standards was normally the task of industrial engineers using work study techniques. A work study is a detailed examination of the procedures, operations, and behaviors required to accomplish a task. It can take a number of forms, but all require an extensive measurement of the work activity itself to determine a production standard.14 This work study approach is increasingly being applied to services industry sectors as well.

The requirements for measurement, as opposed to appraisal, are strict. Essentially performance measurement requires a ratio scale, the most demanding type. A ratio scale requires a zero point. Without this we would not be able to conclude, for example, that one person had produced twice what another person had.15 We would be able to say only that one had produced so much more than the other.

In work measurement the activities (often down to simple movements required to perform a task) are recorded, as well as the time required to complete each motion. Outside influences, such as down time, delays, and fatigue, are built into the calculations and a standard time is developed for completing the task cycle. This technique moves beyond being descriptive when it rearranges the order of activities to attain a more efficient sequence of work (that is, a sequence that takes less time). This is often called a time-and-motion study, a very descriptive phrase but one that has many negative connotations based upon restricting the employee's method of doing the work and applying tight standards.

Activity-ratio studies consist of recording a series of observations of activities. These observations are made on a sampling basis, and ratios between the different types of activities involved in the work cycle are calculated. Using this procedure, one can determine within some specified limits of accuracy the distribution of activities over a day or week.

Production standards consist of standard times obtained by these methods, plus allowances. Quality levels must also be built into the determination of outcomes so that the standard comprises both quantity and quality of production. Measuring performance then means comparing actual times against standard times. Units of production may also be the way in which the actual and the standard are developed. Payment is ordinarily based upon some base rate for meeting the standard, and a bonus for exceeding it.

This brief explanation of the process of measuring performance under a variable pay plan serves to point out: (1) the specific and limited definition of performance under these plans, (2) the complexity of the process, (3) the subjectivity remaining despite the attempts to make the process objective, and (4) the importance of production standards in the process. Although this discussion has emphasized production jobs, performance measurement is applied to a wide variety of service jobs such as finance, IT, sales, marketing, and human resources.

Appraisal of Performance

For most jobs and in most organizations, employee performance is appraised rather than measured. Performance appraisal is a formal method of evaluating employees. It assumes that employee performance can be observed and assessed, even when it cannot be objectively measured. The performance that is evaluated may take the form either of outcomes of the work, or the activity and behavior involved in it.16

Most organizations have some form of performance appraisal. But some employee groups are more likely than others to be covered. Most white-collar jobs, such as clerical, managerial, and professional, are covered by performance appraisal. Studies of the use of performance appraisal indicate that from 75 to 90 percent of all companies surveyed have some form of formal performance appraisal.17 Performance appraisal is used less among blue-collar workers than among white-collar workers. This lesser-use may reflect the use of job-rate pay plans, pay ranges where movement is based upon seniority, and incentive plans. Union pressures may also be an influence since unions typically do not like the use of performance appraisal. Increasingly, performance appraisals are moving more toward the concept of performance management, a process that entails on-going coaching, mentoring, and career development.

Performance Standards

Performance appraisal works by comparing an employee's contribution with some standard. The standard may be a set of criteria or some other person. The methods of comparison vary considerably and will be discussed at length shortly. Whereas performance measurement demands the ratio scale, with its precise requirements, performance-appraisal scales may be nominal, ordinal, or interval.

Both measurement and appraisal require a comparison with a performance standard. It is the performance standard that defines what the organization considers to be performance. As pointed out, this is rather restricted in the case of measurement but may consist of a wide variety of outcomes or behaviors in appraisal.

The job description should be the place to find the important performance standards for the job. The description should state the tasks required by the job and the purpose of those tasks. The next step is to define how well the task must be performed to represent acceptable performance. Depending upon the type of appraisal or measurement system used, this may be done through employee-supervisor conferences, analysis of records, committee work, or work measurement. The more objective the standard, the easier the rating task.

Appraisal systems are often weak in specifying performance standards. However, standards can be established for almost any job. Some statement about expected quantity, quality, and time can usually be made. The statement is preferably quantitative but may be qualitative, and it should be verifiable by records. There has recently been a trend, however, to include performance standards in performance appraisal systems. The popularity of management by objectives (MBO) has encouraged organizations to add goals to their standard performance appraisal instruments.

Methods of Appraisal

Although there seems to be a large number of performance-appraisal methods, there are only two basic types: comparison with a standard and comparison with another person. The first approach requires a well-developed standard and allows direct comparisons of it throughout the organization. The second does not require a strong performance standard and under certain conditions can provide more reliable results.

Comparison with a standard

This approach has several variations, described below.

Graphic rating scales. The most common form of rating against a standard is the Graphic rating scale. This, unfortunately, may be the most common form of the performance appraisal instruments. Very often, however, rating scales are used in conjunction with some other method, usually management by objectives.

A graphic rating scale defines a number of factors or criteria; the rater is asked to appraise the degree for each of these factors that best describes the employee's performance. Ordinarily the factors and degrees are defined to permit point values to be assigned to each degree statement and thus a total score calculated for the employee.

Graphic rating scales may be described as rulers against which employees are compared. A ruler is developed for each factor to be rated. Then each ruler is divided into "inch marks" or degrees. But the analogy should not be carried too far. A ruler is a ratio scale since it contains a zero point. A performance appraisal scale, if well designed, is an interval scale, one whose units (inches, in our example) are equivalent.18

Graphic rating scales typically provide a line for each factor, along which the degrees are arrayed in either increasing or decreasing order. Figure 14-4 is an example of a scaled factor.

The rater may mark anywhere on a scale that is assumed to be a continuum. On other scales, however, the rater must pick the box that best represents the employee's performance. In these scales, the line represents a set of steps instead of a continuum of performance.

The most common performance rating scale is the graphic rating scale with steps. This scale follows the format just described. The factors or criteria are usually those that are organizationally important in determining performance. The reason that the consideration is organizational and not job-related is that a single graphic rating scale is typically used for a variety of jobs within the organization. At best, the factors are outcomes (such as quantity of work) or behaviors (adaptation to change, for instance). At worst they are personal characteristics (such as a good personality). The degree statements can also range from descriptions such as those in Figure 14-4 to a simple scale from "Most" to "Least," with no explanation of what these terms mean.

Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales [BARS] A rating scale that has attempted to eliminate the worst features of graphic rating scales is the behaviorally anchored rating scale (BARS). This type of scale is job-specific, or at least occupationally specific. The factors and the degree statements are arrived at through a complex system in which a group of experts who know the content of the job sort out behavior statements.19 The format itself is little different from that of a graphic rating scale, except that the BARS dimensions and steps have been carefully arrived at. Figure 14-5 is an example of a BARS.

Source: Beatty and Schneier, Personnel Administration©, 1981; Addison Wesley Publishing Co. Inc., Reading, MA;

p. 129, Form 8. Reprinted with permission.

It was expected that BARS, with its procedure and job specific nature, would allow raters to make better judgments. However, the results have not been very encouraging: the use of BARS does not seem to significantly reduce the rating errors found in graphic rating scales.20

Behavioral Observation Scales. The research into BARS has led in turn to at least two other types of rating scales, the behavioral observational scale (BOS) and the behavioral discrimination scale (BDS). These scales are developed like the BARS but are themselves different. A BOS states a behavior and asks the rater to indicate where on a scale the employee's performance falls, as illustrated in Figure 14-6. The BDS is more complex: for each of the behaviors – generic ones in this case – the rater is asked to judge three areas: (1) opportunity to exhibit the behavior, (2) satisfactoriness of exhibiting the behavior, and (3) level of performance of the behavior.21

Rating the Rating Scales. Since rating scales are the most common performance appraisal method, they have the advantage of familiarity. The graphic rating scale also has the advantage of being applicable to a large part of the employees of an organization. When well designed, it provides a clear definition of the criteria the organization considers to constitute "good" performance. This definition enables managers to discuss the relative performance of an employee against a known standard.

The preceding statement assumes that there is agreement about the meaning of factors and their degrees among managers and between managers and employees. If there is no such agreement, the "standard" is an illusory one and becomes a disadvantage. The advantage of commonality can also be seen as a disadvantage if in fact there is a great deal of difference among the performance factors required in different jobs. Different jobs may really require that different factors be used. This is a basic argument for the use of BARS. A third disadvantage centers in developing a total score for employees. The summation of a number of factors always assumes that a deficiency in one can be made up for by strength in others. Where this is not true, the summated scores are not useful.

From: Performance Appraisal and Review Systems, by Carroll and Schneier. ©1982 by Scott, Foresman and Company. Reprinted by permission.

Weighting is another problem in rating scales. If factors overlap in the behavioral domain that they measure, then some dimensions of performance may be inadvertently over-weighted. Appraisal rating scales are similar to the scales used in job evaluation and have some of the same problems. For instance, the actual weighting of the scales may be quite different from the weights specified when the system was developed. Thus, weights should be applied after the ratings (both job evaluation and performance appraisal) have been completed and checked statistically.

The most common criticisms of rating scales, particularly the graphic ones, are the set of constant errors that occur in rating. The first of these errors is rating everyone too leniently or severely. The second is central tendency. Here the rater overuses the middle of the scale, making it hard to distinguish among employees. The third error is the halo effect. Raters tend to have a global impression of an employee, and this impression colors how they rate all factors. Different levels of performance on different factors are not recorded. Last, and connected with the halo error, are proximity and logical errors. Factors that are next to each other on the rating form are likely to correlate just because of this. Logical errors occur when the rater assumes that two factors are similar and should therefore be rated the same.22

A final area of concern in rating scales is the choice of factors. Advocates of BARS have questioned two things about the factors used in graphic rating scales. The first is the factors themselves. The BARS indicates by its name that it is behaviors that should be used as factors. As will be seen, users of MBO say that outcomes or goals should be used. Both are reasonable approaches. Graphic rating scales are criticized when they use personal characteristics as factors. A focus on behavior and/or results improves the actual observation ability of the raters; they can focus on what they have observed. All this indicates that systems that have included the participants in their development will have a better chance of success.

The second criticism from BARS advocates is that using a single rating scale over a large number of jobs is not useful since the behavioral dimensions of jobs differ greatly. This is a dilemma. While the criticism is valid, the solution, that of having many different scales, has its own difficulties. It is expensive and time-consuming to develop a series of rating scales. This is a major complaint about BARS. Employing many scales also makes it more difficult to directly compare employees in different jobs.

Despite all of these criticisms of rating scales, the Human Resource Director has to be able to use them in a merit pay program since this is the most common program used by organizations. Where there are common factors and a summated score, the task is easy (if not always accurate) since all employees can be placed upon a single ranking, making the performance axis complete. If constant errors are prevalent in the rating process, the responses may need to be statistically spread out on the scale. The best results can be obtained if (1) unambiguous descriptions of factors and degrees are developed, (2) the ratee does not self-evaluate, and (3) the raters have been trained.

Behavioral Checklists. A behavioral checklist is a set of statements about behaviors that an employee might engage in on the job. The rater's task is to indicate whether the employee does or does not engage in the behavior. This puts the rater in the position of recording behavior rather than evaluating it and should lead to more reliable reporting. A behavioral checklist can be made more complex by requiring the rater to indicate how much the employee engages in the behavior.

A special form of a behavioral checklist is forced choice. In this method the rater is presented with a set of behaviors and is requested to choose the most descriptive and least descriptive behaviors of the employee. In a set of four items, two appear favorable and two unfavorable. But only one of the favorable items adds to the total score and only one of the negative ones detracts from it. The value of the items is determined statistically by an item analysis of successful and unsuccessful employees. The scores are not known to the rater, who is in essence rating blind. This last feature is intended to reduce the constant errors of rating scales.

The forced-choice method was developed by the armed forces, where the problem of leniency had led to everyone being rated excellent. The method does reduce error and has the advantage of having the rater record rather than evaluate. But forced choice also has some strong disadvantages. The secrecy feature leaves raters questioning how they in fact rated the employee. This is uncomfortable and leads to resistance to and subversion of the method. As a method of providing feedback to the employee, forced choice is not useful since neither rater nor ratee knows what the important behaviors are. In fact, the armed forces have abandoned its use.

Nevertheless, in merit pay programs, any behavioral checklist that evaluates employee behaviors to provide an overall score would be useful in establishing the relative performance of employees.

The Critical Incident Method. The critical-incident method involves determining those behaviors that are critical to success or failure on the job. When the rater observes these behaviors in the employee, he or she records them, along with the date, and places the data in the employee's performance record. This method was also developed to overcome the constant errors of rating scales.

An informal version of this method is often used in other performance appraisal formats where the rater is asked to indicate what the person's job is and how well the person is doing it. In some cases, this format is just one part of the system, but in others it constitutes all of it. The newer methods of performance appraisal, such as BARS and BOS, use critical incidents as their items.

The primary advantage of the critical-incident approach and the accompanying performance record is the amount of observable information that is available for feedback and judgments. Equally important, it gives the manager a means of observing and encouraging employees.

The usefulness of the critical-incident method in a merit pay program, however, may be minimal. The method typically does not offer any way to summate the rating of an employee, so the ranking of employees would be a qualitative exercise. The method is also costly to develop, install, and operate since it requires managers to keep a record on each employee. This record keeping in turn fosters the negative feeling among employees that big brother is watching them.

Appraisal by Objectives. This approach, more commonly called management by objectives (MBO), compares the employee against a standard of expected results. It clearly differs from behavioral checklists and the critical-incident methods, which focus on behavior. MBO requires three things: (1) a set of clearly defined goals, (2) participation of both manager and employee in setting the goals, and (3) feedback to the employee as to how well he or she is progressing toward the goals.23 Theoretically, MBO ought to be an effective method of appraising employees and, as its name implies, managing people. Its principles virtually coincide with Locke's goal theory of motivation.24 And from a practical standpoint it is job outcomes that are important to the organization, for it is these outcomes that the organization most likely wishes to pay for.

So why doesn't MBO always work? There are a number of practical problems. One set of difficulties comes from trying to make goals clear and explicit. Not all important goals, for instance, qualitative goals, can be neatly defined. Vagueness in goals may give employees the maneuverability they need to get the job done in a dynamic environment. In fact, in a dynamic environment attempts to set goals may be futile. Finally, focusing on particular goals may lead employees to ignore other parts of the job.

A second area of concern is the participation of manager and employee in goal setting. This requires a level of trust that is hard to achieve in a situation of uneven power. The employee can perceive joint goal setting as manipulative if the relationship with his or her manager is not good. In addition, a natural tension exists if we assume that goal theory is operating. According to goal theory, more productivity is a result of higher goals being set and accepted by the employee alone. Goal setting is a difficult task to handle within the supervisor-subordinate relationship. Participation takes a great deal of both parties' time. One or both may feel the time investment is not worth the effort.

Third, the information required to provide feedback to the employee may not be developed in the organization or may be impossible because of the nature of the task. MBO also assumes that the outcomes of work are the only important variables to consider in defining good performance. Often, however, how the work is done is as important as what is accomplished. The former variable is hard to program into MBO.

As a performance appraisal method for a pay-for-performance program, MBO is not very useful. There is no way, other than qualitative judgments, to decide who is doing better or worse, other than accomplishing or not accomplishing goals. This leads to a nominal measurement, but more is needed for the program to operate. MBO is much better suited to bonus or incentive systems (the topics of Chapter 16.)

Comparison with Others

Employee comparison systems compare employees directly with each other and not against any standard of performance. This gives the organization a relative positioning of all rated employees. Although it is possible to rate employees against each other on several factors, employee-comparison systems typically rely on a global evaluation of employees.

The simplest form of employee comparison is rank-order rating, which requires the rater to rank all the employees from best to worst. This method certainly has the advantage of simplicity. It also is not unrealistic, since, as discussed, most uses of rating scales have a global impression that influences their ratings anyway. Ranking is facilitated by providing raters with a pack of cards, one for each employee. The rater then numbers the cards in sequence. A major drawback to this system is the difficulty of keeping the performance of many employees in mind at one time. Ranking systems often involve a number of raters ranking their employees and then amalgamating their lists into a master list. This is usually done by having all raters meet together with their manager as arbitrator.

One response to the size problem just noted is alternation ranking. In this method the rater indicates the best performer, the worst, the next best, the next worst, and so on until all employees have been rated. More complex is the paired-comparison method (discussed in Chapter 11 among the ranking methods of job evaluation). The advantage of paired comparison is that the rater makes a judgment about two employees and not one employee and all others. The problems with paired comparison are the large number of comparisons required when the number of employees exceeds about six and the complexity of the data analysis that follows all the comparisons.

The product of all these methods is a rank ordering of all employees rated. Rank ordering works best where all employees occupy similar jobs. Large engineering organizations are likely to use this kind of ranking for all their engineers. Like all sets of rankings, these rankings order employees by their performance but tell the organization nothing about how much better one person's performance is than any other's. They also tend to make some very fine distinctions that may not actually exist. Scores can be obtained in these methods if the employees are rated on a number of factors or if they are rated by more than one rater.

A major variation of employee-comparison systems is the forced-distribution system. Here the rater distributes all employees among finite performance categories such that a prescribed percentage of employees are in each category. A typical distribution would be (1) the bottom 10 percent, (2) the next 20 percent, (3) middle 40 percent, (4) the next 20 percent, and (5) the top 10 percent. Again, this may be done globally or for a number of factors. Note that this system assumes that employees form a normal distribution in terms of their performance.

Advantages and Disadvantages. As indicated, a major advantage of employee-comparison systems is their simplicity. Because of this, it has also been claimed that they are more accurate. Moreover, it is easier to make relative judgments than to make a comparison against a standard. Finally, these methods take advantage of, instead of fighting, raters' tendency to make a global judgment.

In merit pay systems, either rankings or forced distribution are the most prevalent practices. Either provides a relative positioning of employees that can be compared with their relative position in the pay range. In fact, all the methods of comparison with a standard will generally trend toward a ranking or a forced distribution.

But for other purposes, employee-comparison systems fall short. Other than the ranking itself, there is a definite lack of information to provide a basis for discussion with the employee. Where a global ranking is used there is no agreement as to what the appropriate criteria are. The forced-distribution system does provide a standard, but it is the group average, which offers little help to the manager who needs to discuss individual performance with an employee.

A disadvantage shared by all employee-comparison systems is that of employee comparability. This has two aspects. The first has been mentioned: are the jobs sufficiently similar? The second is whether employees are rated on the same criteria. It is likely that one employee rates high for one reason and another rates low for an entirely different reason. Another disadvantage is that raters do not always have sufficient knowledge of the people being rated. Normally the immediate supervisor has this knowledge, but in large ranking systems, supervisors two and three levels removed often must do the rating. The very size of units also poses a problem. The larger the number of employees to be ranked, the harder it is to do so; on the other hand, the larger the number in the group, the more logical it is that there is a normal distribution. This brings up one last problem. If the manager knows that some employees must be rated below average, he or she will start thinking of those employees that way. This leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy: the manager now treats them as if they cannot do well, and they respond by not doing well.25

ADMINISTRATION OF PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL

Unlike job evaluation, which is used mostly for compensation purposes, performance appraisal is used in most Human Resource functions. In addition, the decision making in performance appraisal is done by the manager and not Human Resources. Human Resources typically designs the system and oversees its operation. This is not an easy task. Performance appraisal is not something that managers look forward to, and thus they will put it off unless required to do it. To the extent that they see the process as belonging to Human Resources and offering little help in managing their employees, managers not only avoid it but may also resent the time taken to do the appraisals.

Besides the design of the performance system itself, the major administrative questions that arise are when it should be done, by whom it should be done, and how its operation can be improved.

Timing

Ideally, performance feedback should occur as the job is being performed. If adequate feedback occurs, a great deal of the emphasis on the performance interview would be unnecessary. There is also the question of when formal ratings need to be done in order to be coordinated with pay increases. One argument is that the two should take place as close in time as possible. This way the performance-reward connection is clear in the minds of the employees. The greater the time lag, the less likely an employee will see that what he or she did was related to the pay increase. On the other hand, some argue that close timing makes it difficult to create a meaningful change in the employee's behavior, because he or she will be very defensive if there is negative feedback. Regardless, a current performance appraisal must be available for all employees when the time comes to allocate increases under a pay-for-performance program.

Raters

The clear answer to who should do the rating is the person who best knows the employee's performance and is in a position to judge. This could be the supervisor, a peer, a subordinate, a customer or even the person being rated.26 The supervisor makes almost all formal appraisals in organizations. But often this is not the person who knows what the employee is doing, or how well. The best argument for having the supervisor do the rating is that this is the person whom the organization wishes to be seen as having the power to reward and punishment.

Higher-level supervisors may also be useful raters, assuming they have a chance to observe the employee's behavior. Like the other sources, their advantage is a different perspective. A supervisor one or two levels removed is less likely to be influenced by immediate events and is more likely to look at the employee's customary behavior or beliefs.

Peers are persons who do have a great deal of information about the person’s performance. An advantage is that they are not as influenced by some of the organizational considerations that plague supervisory ratings. Despite this they present problems. For one thing, they tend to be even more global than supervisory ratings, making differentiation among factors difficult. Mainly, though, all parties resist the idea. Supervisors do not like giving up their power, and employees are concerned that their peers will have their own interests at heart. The employee may perceive the situation as a zero-sum game whereby the peer rater will deliberately give a low rating so their own rating can be higher.

Others who might serve as raters are a subordinate, the person being rated, or a client. Each has unique information that might be useful in a complete evaluation, but that by itself might be incomplete or biased. Each has something different to contribute that would add to the overall evaluation. Combining these different types of raters into a program is a method called 360-degree feedback.27 This method is a tool that provides each employee the opportunity to receive performance feedback from his or her supervisor and four to eight peers, reporting staff members, coworkers and customers. Most 360-degree feedback tools are also responded to by each individual in a self-assessment.

The research evidence that the average of ratings made by several raters is superior to the rating made by one person tends to support the multi-rater approach just discussed. The problem often is identifying the second or third raters. If there is less emphasis on selecting raters only from the organizational hierarchy, it may be easier to identify those who are capable of judging performance. It is important to identify what behaviors a prospective rater knows about. For instance, customers have the best perspective on the selling behaviors of salespeople. This method has proven to be effective in improving feedback to employees and is particularly good for the career development and training uses of performance appraisal. For merit pay considerations the use may be considerably less.

Improving Performance Ratings

Good performance ratings begin with rating the right things in the right way. The performance appraisal format should emphasize the job outcomes and behaviors, not the characteristics of the person. The format of the appraisal system should be appropriate to the organizational circumstances. This chapter has presented several possible formats all of which are useful if properly applied. A basic problem is that the performance appraisal system is used for many purposes and the appropriate format may vary with the use to which it is put.

The rating process needs to be understandable and as easy as possible on both the supervisor and the employee. Where supervisors see this as a chore to be dispensed with, and employees do not see any connection between their ratings and their pay, the system truly has no purpose. A performance appraisal interview is a tense situation under the best of conditions for both the supervisor and the employee. Appraisals can generally be improved by increasing their frequency. Since current events outweigh past events, when feedback is given more often, any disparate issues of the past get diluted with consistently improved ratings. Perhaps three months is the longest that should elapse between feedback and ratings.

A powerful device for improving performance ratings is rater training. Discussions of the meaning of the factors and the definitions of scale, along with practice in rating, help improve the reliability of ratings. There are a few types of training programs:

- Rater-Error Training (RET). This type of training is directed at reducing the response errors discussed earlier, such as leniency, halo effect and others. Studies show that RET does reduce error and bias but does not improve accuracy.

- Rater-Accuracy Training (RAT). This related type of training is aimed at developing observational skills that improve the accuracy of ratings. RAT is also called Frame of Reference [FOR] training. The purpose is to define the behavioral dimensions and give examples to aid the rater in making more accurate ratings.

- Decision Making Strategies. This type of training focuses on gather, store, retrieve and weight information to be used in making evaluations.

Each of these types of training has it's uses and limitations. The best training is to incorporate aspects of all these approaches into a single training program. Given the importance of good ratings in a pay-for-performance program, it seems absolutely necessary that raters be trained.28

SUMMARY

The purpose of having pay ranges is so the organization can reward employees for factors other than the value of the job. Performance is a primary factor other than the job for which organizations wish to reward employees. This chapter suggests a method for clearly rewarding performance within the context of the typical salary structure, that of a merit pay program. Such programs, however, need to be comprehensively designed. Merit pay is not always possible, nor desirable. The advantages and the costs of such a program should be carefully considered before installing such a program.

Merit pay programs operate by relating all salary increases resulting from adjustments to the salary structure on the basis of performance. The goal is to correlate the position of the employee in the pay range with their relative position on a performance scale. The result of the program is this: employees whose salary is at the low end of the range and whose performance is high receive large increases; those whose performance matches their place in the rate range receive average increases; and those whose performance falls below their place in the pay range receive no increase. These results differ greatly from the usual distribution of salary increases given by an organization.

Any merit pay program requires the organization to have a good performance evaluation system. Where possible, performance should be measured, but this requires that there is some clear outcome from the job that is the result only of the labors of the person on that job; this is not very likely in an organizational setting. Performance appraisal is the most common form of performance evaluation. Methods of appraisal involve comparing the employee's performance to some standard. This may be some form of rating scale, standard of performance, goals and objectives, or other employees' performance. No one method can be said to be superior, and all methods have problems that put their use into question. Ongoing assessment of the performance appraisal results is necessary if the merit pay program is to be seen by employees as a fair and reasonable way to allocate increases.

Footnotes

1 Heneman, R.L. & Gresham, M.T., "Performance-Based Pay Plans" in Smither, J.W., Performance Appraisal: State-of-the Art Methods for Performance Management, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1998.

2 Lawler, E., Mohrman, S. & Ledford, G. Creating High Performance Organizations: Practices and Results of Employee Involvement and TQM in Fortune 1000 Companies, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1995.

4 Kelley, C., "Making Merit Pay Work" American School Board Journal, National School Boards Association, 2000.

5 Fox, J., Scott, K., & Donahue, J., "An Investigation into Pay Valence and Performance in a Pay-for-Performance Field Setting", Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol.14, 1993. pp. 622-636.

6 D. C. Feldman and H. J. Arnold, Managing Individual and Group Behavior in Organizations (New York, McGraw-Hill, 1983, pp. 296-301.

7 E. E. Lawler, Pay and Organizational Effectiveness (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971).

8 Lawler, E., & Jenkins, G. "Strategic Reward Systems" in Dunnette, M. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2nd Ed. Vol. 3, Palo alto, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1992. pp. 1009-1055.

9 H. H. Meyer, "Pay for Performance Dilemma," Organizational Dynamics, Winter 1975, pp. 71-78.

10 D. McGregor, "An Uneasy Look at Performance Appraisal," Harvard Business Review, May-June 1957, pp. 89-94.

11 Seltz, S., & Heneman, R., Linking Pay to Performance, Scottsdale, AZ. World at Work, 2004.

12 Byars, L. & Rue, L., Human Resource Management; 8th Ed. Boston, McGraw-Hill, 2006.

13 Landy, F., & Farr, J. The Measurement of Work Performance: Methods, Theory and Applications, New York, Academic Press. 1983.

14 Heizer, J., & Render, B., Operations Management, 6th Ed. Chicago, Pearson Education, 2005.

15 Gregory, R. Psychological Testing, Chicago, Pearson Educational, 2006.

16 Grote, D. The Complete Guide to Performance Appraisal, New York, AMACOM, 1996.

17 Bureau of National Affairs, Performance Appraisal Programs, Personnel Policies Forum Survey No. 135 (Washington D.C., 1983).

20 Schriesheim, C., & Gattiker, U. "A study of the Abstract Desirability of Behavior-Based v. Trait-Oriented Performance Ratings" Proceedings of the Academy of management 43 1982. pp. 307-311.

21 Goffin, R., Gellatly, I., Paunonen, S., Jackson, D., and Meyer, J. "Criterion Validation of Two Approaches to Performance Appraisal: The Behavioral Observation Scale and the Relative Percentile Method" Journal of Business and Psychology, vol. 11 #1, September 1996, pp. 23-33.

22 Murphy, K. & Cleveland, J. Understanding Performance Appraisal: Social, Organizational and Goal-based Perspectives, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 1995.

24 G. P. Latham and E. A. Locke, "Goal Setting: A Motivational Technique That Works," Organizational Dynamics, 1979, pp. 68-80.

25 P. H. Thompson and G. W. Dalton, "Performance Appraisal: Managers Beware," Harvard Business Review, January-February 1970, pp. 149-57.

26 Milkovich, G. & Newman, J. Compensation, 8th Ed., Boston, McGraw-Hill, 2005.

27 Edwards, M. & Ewen, A. 360-Degree Feedback: The Powerful New Model for Employee Assessment and Performance Improvement, Toronto, American Management Association, 1996.

28 London, M, Mone, E., & Scott, J., "Performance Management and Assessment: Methods for Improved Rater Accuracy and Employee Goal Setting", Human Resource Management., Winter, 2004. Vol. 43, # 4; p. 319-336.

Internet Based Benefits & Compensation Administration

Thomas J. Atchison

David W. Belcher

David J. Thomsen

ERI Economic Research Institute

Copyright © 2000 -

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

HF5549.5.C67B45 1987 658.3'2 86-25494 ISBN 0-13-154790-9

Previously published under the title of Wage and Salary Administration.

The framework for this text was originally copyrighted in 1987, 1974, 1962, and 1955 by Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights were acquired by ERI in 2000 via reverted rights from the Belcher Scholarship Foundation and Thomas Atchison.

All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced for sale, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from ERI Economic Research Institute. Students may download and print chapters, graphs, and case studies from this text via an Internet browser for their personal use.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 0-13-154790-9 01

The ERI Distance Learning Center is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: www.learningmarket.org.