Chapter 13: Individual Salary Determinations

Overview: This chapter examines how to set pay for individual employees, taking into account salary structures, rate ranges and skill-based pay plans.

Corresponding course

81 Salary Structures and Pay Delivery

INTRODUCTION

From the viewpoint of the employee, the end product of any compensation program is a paycheck. The decisions regarding the type of salary administration and/or structure system to be used do not, by themselves, deliver a paycheck to the employee. The salary determination must be personalized by making a further set of decisions.

The first compensation decision, the pay level, is an external organizational decision that determines the organization's competitive posture toward its human resources [Chapter 8]. The second major compensation decision is an internal organizational decision involving the structuring of the jobs within the organization [Chapter 11]. Putting these two decisions together in a salary structure provides the wage, or range of wages, that the organization perceives as equitable for each of its jobs [Chapter 12]. Although pay rates are determined for jobs, it is people who receive paychecks. The next decision to be made, then, is whether all people on a particular job are to receive the same pay or different pay; and if different, on what basis and how? These are not trivial questions.

Almost all workers are paid through systems that provide for variable payment for their jobs. Such systems reflect the realization by management and employees that it is important to reward more than just minimal performance on the job. Thus, management seeks to reward performance through merit-based and incentive pay systems, while employees seek to have learning, proficiency and seniority rewarded.

WHY VARIATION IN PAY?

One way of answering this question is to assume that there are two decisions employees make in their jobs; the decision to participate and the decision to produce.1

The Decision to Participate

The decision to participate assumes the employee maintains an equilibrium between the inducements the organization offers and the contributions he or she is asked to make. The organization must maintain, at a minimum, a balance of these two in the mind of the employee, or better yet, a balance in the employee's favor. This idea is described in a theory called Equity Theory and pay system decisions are seen as focusing on individual equity. Equity Theory states that a person compares his or her "inputs" or contributions with the "outcomes" from participation (I/O ratio). When this is hard to do directly, the person compares his or her I/O ratio with some other I/O ratio. Anything the person perceives as relevant goes into these input and output considerations.2

Inputs and Outputs. Compensation decisions often focus upon the value of the job, both in the marketplace and within the organization. Although these are critical input factors, neither organizations nor individuals would be satisfied by making the employment exchange solely on this basis. To explain, compensation inputs can be classified into three general areas: job, performance and personal.3 Pay system decisions must incorporate the performance and personal factors into compensation, in order to provide a regular paycheck perceived as equitable to the employee.

Equity as a Cognitive Process. People's perceptions determine whether their pay situation is equitable. Not all individuals within an organization are likely to perceive their pay situation the same, nor is the organization (through its management) likely to see the situation the same as the employees. This makes the creation of equity in the organization a difficult and recurring problem, one that needs to continually be addressed as it continues to evolve over time.

Influence. Organizations are not powerless in this cognitive process. They can influence the perceptions of the employees in a number of ways. First, they can clearly define the inputs required of the person. This allows the person to accept or decline the exchange in the way that a student stays or leaves a course after the professor hands out a syllabus. Second, organizations can affect (through communication and influence) the inputs and outcomes the person focuses on. Third, they can influence employee responses to inequity. For example, if an organization wishes to retain people, it may make quitting an unattractive way to solve feelings of inequity.

The Decision to Produce

Organizations seek three things from employees: (1) membership, (2) role behavior and (3) innovative and spontaneous behavior.4 Membership includes remaining with the organization and being present for work regularly. It provides consistency to the organization's labor force and reduces staffing and training costs. Role behavior consists of doing the job as it is described and/or assigned. This is also needed for consistency and coordination of activities within the organization. To the extent that role behavior is explicitly spelled out and is seen as the basis for the person's input to the organization, this requirement is also covered under the decision to participate. However, not all required role behavior is easily spelled out in jobs, and all jobs have areas of discretion that allow the person freedom in accomplishing tasks.5

Innovative and spontaneous behavior addresses the organization's need for the person to adapt what he or she is doing, and how it is being done, to the constantly changing circumstances within the organization. The decision to produce, then, moves the person beyond the minimum required just to maintain membership. It is what most managers call motivating their employees. A useful framework for this decision is provided by expectancy theory.6 This theory has three basic parts:

- valence,

- the performance-reward connection

- the performance-effort connection.

Valence. In expectancy theory valence means the strength of a reward. Does the person want the reward the organization is offering? Since our subject is pay, we can be confident that the answer is yes – but not to the same extent for all people. People differ in how valuable money is to them compared with other things on and off the job. The advantage of pay as reward, though, is that it is seen as a path to many different types of need satisfaction.

How much increase or difference in pay does it take to make the person respond? This is the difficult question of exactly what is the proper size of a meaningful pay increase (SMPI).7 The organization must worry not only about whether pay is a motivator but also about whether it is offering enough to make it worthwhile for the person to produce beyond the minimum. As with the value of pay, the appropriate SMPI differs with a number of characteristics of the person, including current pay, age, experience and type of job.8 And with valence, perception is everything: the strength of the reward ultimately lies in the eyes of the beholder.

The Performance-Reward Connection. This may be the most important part of the decision to produce.If the individual does not see the rewards he or she wants as being contingent on the behaviors or outcomes the organization wants, then the organization is not likely to obtain those outcomes. This connection would seem to be obvious, but in fact it is not. Managers find it difficult to always define the results and behaviors they desire. Also, it is difficult to measure and/or appraise whether these outcomes have occurred. In short, the definition of performance is difficult in and of itself.

The individual must understand what is requested and see its connection with the reward. This, like all understanding based on communication, is hard to realize perfectly. Most organizations claim they have a merit system of pay, but most employees do not perceive that merit is the primary basis on which pay adjustments are made. In some cases, this perception is valid in that the organization says it uses merit but does not; in other cases, the organization is rewarding merit but is not accurately communicating this fact to the employees.

The Performance-Effort Connection. People must feel that their efforts will affect their performance.There are many jobs in which variations in performance are impossible or inconsequential. To try to connect performance to reward in such jobs frustrates the incumbent. Also, individual effort is not a useful gauge in the many jobs whose tasks take two or more people to accomplish. Finally, the effort-performance connection highlights the fact that the person must perceive that he or she can adequately perform the task. All of these subjects should be taken into account in designing a pay system (and will be taken into account in some manner, even if by the default copying of some other organization's design and definitions).

RATE RANGES

The major way in which organizations allow for factors other than the job to enter into the determination of an individual's pay, is to develop a range of pay for each job or grade of jobs. A rate range is a range of pay determined by the organization, to be appropriate for anyone who occupies a particular job. A rate range consists of a minimum pay rate (the beginning hire rate), a midpoint (the market or job rate), and a maximum (the highest rate the organization is willing to pay for the job). The following sections cover single-rate pay systems, the rationale for rate ranges, two types of rate ranges, the manner in which a pay rate is set for individuals within a range, and the dimensions of range rates.

Single-Rate Pay Systems

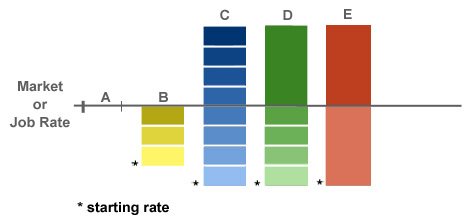

Before discussing various aspects of rate ranges, we should first consider a situation in which there is no range. There is a single rate paid for the job and the individual receives just that rate. This pay rate is the market rate and paid for a job or a pay grade. This is illustrated in figure 13-1, option a.

If a job rate is used, the pay line provides the job rate. The individual is paid in accordance with the number of points assigned the job by the job evaluation system, by the competitive value determined from a salary survey, or by the competitive value provided by a research analysis product such as ERI's Salary Assessor® software. Where the grade rate prevails, the individual is paid in accordance with the pay grade assigned to the job.

This type of system is useful where performance variation and/or other personal characteristics are nonexistent or unimportant. Not all jobs allow for a significant difference in performance. Some assembly–line positions and entry–level service positions have very little discretion, so concern with differences in output or behavior are minimal. Other circumstances that lead to the use of single-rate systems are (1) a strict technology that controls the output and (2) jobs for which the training time is short – a couple of hours or so – thereby making a learning curve inoperative. The individual in this type of system is paid for his or her time on the job and for completion of the job as directed.

Single-rate systems are simple to administer. Once the pay rate of a person's job is identified, no further decisions need be made as to how much he or she is to be paid. The system can operate successfully if (1) there is little variation in output and (2) it is acceptable to the parties involved. Unions often like single rates because they eliminate judgment-based differences in pay.

Rationales for Rate Ranges

Any time individuals on the same job differ significantly in performance or personal characteristics that are perceived as relevant either to the organization or the person, differentiation by means of rate ranges is in order. In most large organizations the rationale is the need for performance differences, but in some cases industry practice is also a major reason.9 Thus labor-market demands may also be a significant factor.

Rate ranges can serve other purposes for organizations. Retention is one of the most important of these. Experienced personnel can be made difficult to hire away by paying them above the market rate for the job. This is seen by the person as a significant reward for membership. Where there is a significant quality variation among people on the job, a rate range may represent an attempt by the organization to retain the best employees by paying them on the basis of quality.

Although performance is the reason most often given for rate ranges, this rationale should be scrutinized. Is movement in the range in fact related to performance? Studies have challenged this assumption and mostly found that performance was a very poor predictor of pay rate.10 There must be more than just an actual connection between pay rate and performance: there must also be a perception by the individual that this connection exists. The need for this perception makes communication very important in pay systems.

A further rationale for rate ranges is employee expectations. Few people are content to earn a pay rate and have to be dependent on changes in the total wage structure for any increases. For raises in particular, they may see that length of time on the job is an important input and expect a reward for it. They may also see a number of factors other than performance as relevant to movement within the range. Personal factors having to do with the job are a good example. For instance, many employees who are going to school part time to increase their work knowledge base, perceive that they should receive something for this. Employees may also perceive that they should receive more pay for a variety of non-work-related factors that will increase their personal expenses. Some of these factors, such as the birth of a new baby, may be very important to the person but seen as irrelevant by the organization. Others, such as the person's gender, may be illegal to use as a differentiator of pay. It should also be noted that although some employees perceive the need for a rate range, they do not feel that performance should be the basis for this range.11

Another rationale for rate ranges may be collective bargaining. In contract negotiation the organization may agree to rate ranges or to an expansion of rate ranges as an alternative to a general increase. The union is likely to bargain for ranges in terms of movement within the range by seniority. The connection of performance and reward is not well served in this case.

Types of Ranges

Having made the argument that rate ranges are useful and expected, we turn to how to develop rate ranges.

Step ranges. The most common form of a pay range consists of a series of steps, usually a specified distance apart, either in percentages or flat amounts.12 Step ranges may vary considerably in number of steps and the total range the steps cover. Clearly these two variables, in combination, will determine the size of each step. The point is that there are three variables present, and the determination of any two will decide the third.

Two basic types of step ranges are common. The first consists of a starting rate and a job rate (assumed to be the market rate), as in the single-rate system. New employees are brought in at the starting rate and then moved up to the job rate in a series of steps. If done properly, this movement corresponds with the learning curve of the job. The market rate is the maximum, since it is assumed that once the person has learned the job, performance differentials are minimal. This kind of system is illustrated in figure 13-1, option b. In this situation there would be a number of steps, most commonly three, between the starting rate and the job rate. This type of step system is most common in semiskilled blue-collar jobs.

The second type of step system places the market rate not at the top of the range but at the mid-point of the range. Other places, such as the one-third point or the two-thirds point, are also possible, but the mid-point is the most common. Employees are hired at the starting rate, as in the other step system, and progress to the midpoint over time, is on the basis of acquiring job proficiency. Thus, a person at the midpoint of the range is assumed to be a satisfactory performer. Movement above the midpoint is assumed to be for performance, or other characteristics beyond the normal or average. This type of system is illustrated in figure 13-1, option c. It is used in a wide variety of office nonexempt jobs and entry-level exempt jobs where performance is important but not critical.

These two types of rate ranges are not mutually exclusive in an organization. Entry-level pay grades may have the type of range that ends at the midpoint, while higher grades have ranges extending beyond the market rate. The rationale for such a system is that the discretion in higher-level jobs in the organization allows for performance differences not permitted in entry-level jobs.

Movement within grades will be discussed later, but one point should be made here. A person who progresses from one step to the next usually retains the new step even when the overall salary structure is changed. In this way, adjusting the salary structure to meet labor-market changes automatically becomes a general increase for employees in a step system.

There is a further consequence of this type of system: all people tend to move to the top of the grade over time. Even if movement is by performance, a person can eventually reach the top and stay there regardless of future performance. This phenomenon in turn has a dramatic effect on the total salary expense. In a period of normal growth and turnover the average pay for the job classification will probably match the market rate as people start to climb the ladder while others leave. But in a low-turnover, no-growth situation the organization may soon be paying above market rate even if it sets the midpoint of the range at the market, because all the employees in the job are in the top steps.

Open ranges. In order to focus more clearly on performance and to avoid the problems of step ranges, more and more organizations are using an open-pay range. In this system the organization defines the midpoint, the maximum, and the minimum of the range. Any one employee may be paid anywhere within this defined range. The function of the midpoint, as in the second type of step system, is that the average performer would be paid at this rate. Also, as in the second step system, new employees would start at the bottom and move to the midpoint as they learned the job and became average performers. Payment above the midpoint can be reserved for above-average performance. Unlike the second step system, the person's pay is not automatically adjusted when the salary structure is adjusted. At this point, the person's performance is reviewed, and adjustment is made in relation to that performance.

Figure 13-1, options d and e, illustrate two types of open pay ranges. Option d has a series of steps up to the midpoint and an open range above the midpoint; option e has an open range from minimum to maximum. With the increased emphasis on performance in organizations, open-range systems are becoming more popular. They provide more flexibility than a step system in granting pay increases and are more resistant to automatic increases. Finally, open ranges not only may make it easier to reward performance but are also useful when criteria other than performance are to be used.

Dimensions of Ranges

Ordinarily a salary structure would have a number of pay grades with accompanying rate ranges. This number can be a matter of the policy of the organization. Small organizations tend to have a small number of pay grades accompanied by wide pay ranges, broad definition of job titles, a great deal of movement within pay grades, little overlap between grades and limited promotion to higher grades. Some organizations have many grades, which tends to create an opposite set of characteristics.

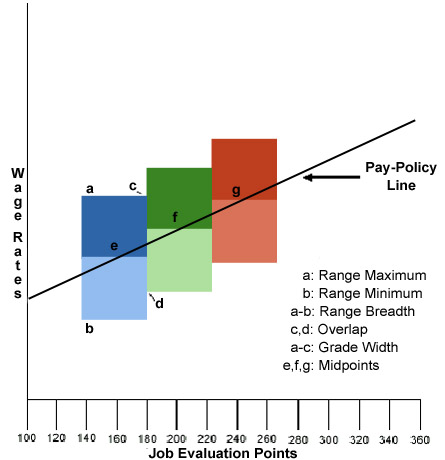

When examining pay ranges we can determine the total salary structure with the help of three characteristics: the breadth of the rate range, the number of pay grades and the overlap (see figure 13-2). If one knows the bottom and top of the salary structure, the slope of the pay line, and any two of the three characteristics just cited, the third will be determined.

Range Spread. The width of a rate range is the distance from the top to the bottom of the range – a to b in figure 13-2. It is the vertical dimension. This spread may be stated in dollar amounts or in percentages. The latter is more common and will be used here. The range spread should vary with the criteria for movement within the range. Assuming that performance is the criterion, the spread would represent the opportunity for performance differences in the job. Where ranges are narrow, the assumption is that performance differences are narrow and vice versa. In practice, administrative/operative jobs have a range spread of 40% or more, professional/management jobs 50% or more and executives 50 to 65% or more.

Factors other than potential performance differences may also affect range spread. Organizations that promote intentionally fast encourage narrow ranges, since people do not stay within one grade very long. A wide range is encouraged if adjustments need to be large to be noticed by employees. Higher grade levels tend to have broader ranges for this reason. Broad ranges can accommodate a wide variety of jobs, as well as variable starting rates among jobs. These broad ranges indicate that the process of determining the market rate is not a precise one.

Establishing range maximums is particularly difficult. There is some logical maximum value for any job, regardless of how well it is performed. Ideally when this point is reached the person is promoted, either to a new job or by upgrading the tasks of the present job. Unfortunately, this may not be possible at the appropriate time. Realistically the person should be told that this is as high as he or she can go in the rate range and that any further salary adjustments will come from general increases.

Some organizations provide steps beyond the maximum of the range. There are usually two rationales for this – seniority and recruiting. Long-term employees who will never be promoted and whose performance remains good are sometimes granted longevity increases beyond the maximum of the range. These usually take place after five or ten years at the top of the grade. Trouble in recruiting and retaining professional and managerial employees can be ameliorated by starting these people quite a way up in the rate range; in order to retain them the organization must go beyond the maximum to provide any significant movement in grade.

Measures of Range Spread. Since the range spread is the difference between the maximum and the minimum of the range it can be expressed as a percentage of the difference between minimum and the maximum divided by the minimum.

| Maximum – Minimum | = Percentage Spread |

| Minimum |

A second calculation that is used is the spread on either side of the midpoint. This is calculated as follows:

| Midpoint – Minimum | = Range Spread below midpoint |

| Midpoint |

Obviously, the maximum could also be used to obtain the range spread above the midpoint.

Midpoints. The midpoint is the most used figure for pay administration. It is ordinarily the mean or median of the pay rates of the survey jobs included in the pay grade in question, so it is the market rate for the grade. The statistic that is related to the midpoint to make it most useful is the

compa-ratio

. This ratio expresses the relationship of the midpoint to a base salary or the market average. A compa-ratio can be calculated for a job, an individual employee, a group of employees or the organization as a whole. The major use of this statistic is for compensation planning and control and will be considered further in Chapter 25.Range Penetration. Another useful calculation that is the relationship of an employee’s pay to the total pay range. This calculation is:

| Employee's Salary – Range Minimum | = Range Penetration |

| Range Maximum – Range Minimum |

Number of grades. The total number of pay grades in the salary structure can be a result of other calculations (mainly range breadth and overlap) or a conscious decision that forces the other two variables to adapt. The number of pay grades is reflected in the horizontal dimension of figure 13-2 (a to c). At one extreme, a structure with a single pay grade would have a minimum and maximum embracing the total salary structure and would include all jobs. At the other extreme, each job evaluation point on the horizontal axis would constitute a separate pay grade. In the latter circumstance two jobs would occupy the same pay grade only if they had identical job evaluation points, a situation that would assume a very accurate job evaluation plan.

A large number of pay grades often coincides with a narrow range, permitting a large number of promotions and multiple classifications in job families in the organization. A small number of pay grades allows for flexibility, in that it assigns people to a wide range of jobs without changing their pay grade. This approach is known as broadbanding. Not surprisingly, the number of pay grades tends to be associated with the size and number of levels in the organization. It also seems reasonable that organizations with a fluid, organic structure would have a minimum of pay grades whereas more structured and bureaucratic ones would have more. Keep in mind that there is no optimum number of pay grades for a particular job structure. In practice, the number of pay grades varies from as few as 4 to as many as 60. But 10 to 16 seem to be most common. With few grades there are many jobs in each grade and the increments from one grade to another are quite large. The presence of many grades has the opposite characteristics.

A number of considerations help to determine the appropriate number of grades for your specific purposes. One is organization size: the larger the organization, the more pay grades. A second, is the comprehensiveness of the job structure. A structure that covers the whole organization will tend to have more pay grades than one that deals only with one job cluster. Third, the type of jobs in a structure makes a difference. Production jobs whose pay policy line is relatively flat will tend to have fewer pay grades than a managerial structure that has a steep slope. The last determinant is the pay-increase and promotion policy of the organization. A large number of pay grades allows for many promotions but entails narrow ranges and a narrow classification of jobs. A small number of pay grades, accompanied by wide ranges, used to be thought of as unreasonable because it would be difficult to control salary administration costs. Today, organizations that use broadbanding have robust analytics and market pricing methods to better control costs.

Overlap. The final pay range determinant is the degree of overlap between any one pay grade and the adjacent grades (c to d in figure 13-2). Overlap allows people in a lower pay grade to be paid the same as or more than those at a higher grade. The rationale for such a phenomenon is that a person at a lower pay grade whose performance is very good is worth more to the organization than a new person at the higher pay grade who is not yet performing effectively. This reasoning seems to work; seldom are there complaints about overlap.

As with the number of grades, overlap can be either a determining variable or the determined variable. Overlap will work well where there are many wide pay grades. A conscious decision to keep overlap to some maximum (such as 50 percent) will reduce one of the other two variables.

Some overlap is desirable, but there are problems. The main one comes about with promotions. A person at the maximum of a rate range, who is promoted to a job in a higher job grade, may start in the new rate range at a higher level than the job rate of the new grade, which should be higher than the maximum pay level in the previous grade. Not giving the promoted person a pay raise is hardly to have promoted them at all. The pay increase associated with this promotion needs to be evaluated in terms of employee motivation and cost controls. Organizations generally set some policy that any promotion be accompanied by some specified minimum increase, such as one step in the new rate range or a specified percentage. The designers of career paths in some organizations reduce this problem by placing the next job in the sequence more than one pay grade above the present one.

MOVING EMPLOYEES THROUGH RATE RANGES

Rate ranges make it possible for different pay rates for individuals in the same job and/or grade level. Operating such ranges calls for some method that differentiates between employees. Such a method must provide a decision framework for positioning each person within the range.

Open rate ranges facilitate a pay-for-performance approach to individual pay determination to be discussed in Chapter 14. The present section will focus on movement within grades in a step system. It should be noted, though, that an open range system can also accommodate the methods of progression discussed.

Step Rates

Most government and many private organizations divide their entire rate range into a number of steps. (One should always be aware of the influence of government systems in compensation. For example, with half the paychecks in Canada being written by governmental agencies, one cannot overlook these step approaches.) This number is a function of the spread of the rate range, the time required to achieve proficiency in the job, whether there are steps beyond the market rate, and a determination of the size of a meaningful pay increase. At least three steps are almost always used. A general step system is illustrated in option c in Figure 13-1.

Step rates facilitate pay increases by determining the increase amount. Of course, it may be possible to move a person two steps, but this is always done in predetermined amounts. Such increases can be considered a disadvantage as well as an advantage. Many organizations prefer to be able to grant a wide variety of increases to better relate pay to their pay-increase policy.

Methods of Progression

All methods of progression specify how a person moves from the bottom of the range to the top of the range. The major difference among them is the criteria for movement. The major methods are automatic progression, merit progression, and a combination of both merit and automatic progression. An organization does not have to restrict itself to only one method; it may use different methods for different jobs or even different methods for a single job at different parts of the rate range.

Automatic progression. This type of progression (sometimes referred to as scheduled increases) consists of pay increases based automatically on length of service. In some situations there are a small number of increases, often in rapid succession (every three months), to the maximum rate for the job. These are jobs in which proficiency can be gained in a short time. On the other hand, some governmental organizations may have many steps (five or more) and grant increases once a year. In these situations, longevity on the job leads to higher proficiency and the organization wishes to reward continuity of employment.

A major source of variation in automatic plans is the nature of the maximum rate, whether it is the market rate or an above-market rate. Organizations that move only to the market rate tend to have rate ranges with fewer steps and a short time frame for progression. They are interested not so much in rewarding longevity as in encouraging job proficiency. Organizations that move beyond the market rate are specifically rewarding longevity on the job; they tend to spread out the progression to the top of the grade over a long period.

Automatic progression does not have to be totally automatic. A fully automatic progression plan is actually a variation of the single-rate or flat-rate system. If all employees can expect to reach the maximum of the rate range after a given period on the job, the assumption is that the maximum is the real rate for the job.

Variation can be introduced in two ways. First, the time period may vary from step to step. For instance, some systems move people rapidly to the midpoint and then much more slowly; the extended steps beyond the midpoint are clearly tied to longevity. The second variation introduces a little merit into the system by either (1) denying movement to the next step for poor performance, (2) giving good performers a double-step jump, or (3) shortening the time period between step increases.

Merit considerations in automatic plans should not be overemphasized. The system is designed to be automatic, and variations are seen as exceptions, not the rule. In most systems that allow either movement ahead or denial of increases, these alternatives are rarely used: the problems they pose for administration of the workplace are not perceived by supervisors to be worth the advantages they offer.

The use of automatic progression has been declining, although it is still probably the norm in many cases. The emphasis on productivity in the United States is translating itself into a search for ways to make employees more productive. Focusing on performance instead of longevity is part of this trend.13

Combinations of automatic and merit progression. We have just seen that some introduction of merit is possible even in automatic progressions that focus on longevity. It is possible also to design progressions that try to balance merit and longevity. These progressions usually let employees focus on different criteria at different places in the pay range.

Probably the most common combination is automatic progression to the midpoint (the market rate) and progression beyond the midpoint based on merit. The rationale for this method of progression is that all employees can be expected to reach average proficiency within a certain time on the job; this period matches the automatic movement to the midpoint. However, not all employees exceed average performance on the job, and movement above the midpoint should be based on performance that is above average. If the organization does a good job of matching time taken to reach the midpoint with time taken to reach proficiency in the job, then labor costs are equalized; if these are out of balance, then labor costs are higher or lower than is optimum.

The rate range can take one of two forms in this case. The first looks like option c in figure 13-1, with a series of steps from bottom to top and the market rate as the middle step. The distinguishing feature of this form is how movement is determined after the midpoint has been reached. In the second form there is a series of steps up to the midpoint but an open range from that point on with movement of any degree possible and decided by merit. This form is illustrated in figure 13-1, option d.

Another method is to combine longevity and merit at all points in the range. Under this arrangement all employees receive an automatic adjustment, but those with above-average performance receive more, such as a two-step jump. It is also possible to hold back those who are not performing well. The latter action is rare but can be effective in probationary situations.

The prevalence of these different methods is hard to determine. It appears that automatic methods are most typical for factory jobs and combination methods most typical in office situations. Automatic-progression methods are simple to administer since they are purely mechanical adjustments made by time in grade. Introducing merit complicates the pay decision by adding a judgment about how well the person is doing the job. Then a way must be developed to incorporate this judgment into a pay increase. This makes administration more complex and, if the judgments are perceived as arbitrary, dissatisfaction about the equity of the system increases. The advantage is that a connection is made between performance and reward, and this may be worth the trouble.

Merit progression. A pure merit progression employs an open rate range with only the minimum, maximum, and midpoint defined, as in option e in figure 13-1. Movement within the range is based strictly on performance, and there are no adjustments for general increases. This pay-for-performance system requires an integration of performance appraisal with pay determination. What we cover here is movement between steps of a pay grade, as in figure 13-1, option c, based on merit. The rationale for merit progressions is that the movement to proficiency is actually an improvement in performance and should be treated as such; people differ in their rate of improvement to proficiency, and this should be taken into account; it is performance that the organization wants and should pay for.

In practice, a merit progression is usually a combination of merit and longevity. The initial decision to move a person from say, step 3 to step 4 is based on performance, but from that time on the person retains step 4 when adjustments to the salary structure are made, thereby remaining at the same relative position in the range. If step 4 is one step above the midpoint, the assumption is that this person is always above average in performance, but in fact the person needs only to maintain a level of performance that will not result in termination. Further, unless the performance-appraisal system is tied consistently to the merit pay adjustments, either the system tends to be seen as arbitrary, or supervisors tend to grant the same increase to all employees and thus destroy the performance-reward connection.

In all step systems most employees eventually get to the top of the pay range, particularly in a bad economy. In a merit progression method, the good performer should get there faster than the average or poor performer. This phenomenon of getting to the top of the range tends to be hidden when the organization is growing and times are good. But when growth stops, then promotions slow up, employees stay in their current job, movement to the top of the range is accelerated, and the organization finds that all employees are at the top of the range. Labor costs thus become very high at exactly the time the organization can least afford that to happen. From the employee's perspective, the only pay increases received are those that occur through salary structure adjustments, and these are likely to decrease in these circumstances. The lack of pay increases makes the potential for feelings of inequity to increase considerably.

Most organizations and their management claim that they use a merit progression system, but in practice up to 80 percent of employees in a stable organization are at the top of their rate range. The problem is compounded when management grants all employees the same pay increase and announces it as a merit increase. This miscommunication destroys the concept of merit. Front-line supervisors in particular, find it uncomfortable to deal with merit pay, which requires them to make competitive distinctions between employees. For these supervisors it is often cooperation and not competition that is important. Since annual pay increases are almost institutionalized in organizations today, this makes merit progression something of a misnomer, especially where organizations simply call all pay adjustments merit increases.

Union acceptance. Unions generally do not support merit-progression systems (as was the case in the Year 2000 when the National Education Association voted against merit pay for teachers). They question the objectivity of performance criteria and see the supervisor rewarding things other than getting the job done. Further, they are interested in getting their members to the top of the rate range as fast as possible. Unions can complicate the merit system through grievances. Some unions will automatically file a grievance if all members do not receive an adjustment or if they do not receive the maximum adjustment. This not only increases administrative costs but considerably burdens the performance-appraisal system.

Non-unionized people in the organization look at what happens to union members, and management knows this. Therefore, management tends to give those not in the union what union members received and maybe a little more. Organizations do try to deal with their nonunion sectors more on a merit basis than on a longevity basis, and to the degree that above-average employees receive more, the merit principle does work.

Rate Ranges and Recruitment

To this point we have assumed that the organization has been hiring people who are just qualified and moving them up in the range as they learn the job. But what if it hires a person who can do the job from the beginning? Clearly this person should be hired at the market rate (the midpoint). In actuality, people are likely to be brought into the organization anywhere up to the midpoint of the range, based upon their qualifications. Thus, a system that ends at the market rate has a flat rate for hiring fully qualified employees.

The labor market may complicate the rate range when there is a shortage of applicants. When it is hard to recruit, a way organizations adjust is to raise the starting pay to wherever in the range it must go in order to obtain people. This may result in hiring rates at the top of the rate range or above. This extreme situation makes any upward movement within the grade difficult or impossible for the person. A person who is then expected to stay in the grade for three or more years before promotion can only look forward to general increases.

Correcting Out-of-Line Rates

The rate range defines the minimum and maximum that a person may be paid for a given job. For a number of reasons an individual's pay may be more or less than the prescribed range. The organization needs policies for dealing with these out-of-line rates.14

Paid Below the Minimum. A person paid below the minimum of the rate range for his or her job is said to carry a green-circle rate. This situation usually occurs when the salary structure is changed upward, and the individual was at the bottom of the rate range. Little question exists regarding the appropriate response: the underpaid employee should have his or her pay raised to the minimum of the range, immediately if possible, or in a minimum of steps. If the person is performing adequately, the difference between his or her rate and the minimum of the range should be made up by the employer.

Of course, it is possible for a number of reasons, that the employee is not worth the minimum of the range. Even so, there are usually adjustments that can be made. For instance, if the labor market is very tight and marginal workers must be hired and retained, a lower classification involving job redesign to accommodate the person's skills would be in order. This same reasoning could apply to older and handicapped employees who cannot fully carry out their jobs. On the other hand, redesign may be unnecessary where there is already an entry-level job to which the person can be assigned. A trainee rate may be appropriate if the employee is still learning the job.

Usually there will be a few underpaid employees, and a policy of bringing their rates immediately into line, protects the integrity of the pay system. If many employees are underpaid, a careful review is required: not only may the costs of adjustments be high, but also equity between the newly raised employees and other employees on the job may require a phasing in of increases. Also, all underpay situations should be examined for racial or gender discrimination.

Paid Above the Maximum. A person paid above the maximum of the range for his or her job is said to receive a red-circle rate. This is a common problem in organizations, that stems from a number of sources, and is more difficult to deal with than the problem of underpaid employees.

Solutions to overpay vary from doing nothing, to reducing the pay to the top of the range. Both approaches can cause equity problems, both in others and in the person affected. The most common solutions are the following:

- Freeze the pay until general increases catch up with the current pay.

- Transfer or promote the person to a job in an appropriate pay grade.

- Freeze the pay for a limited period, such as six months. Then attempt either of the previous strategies. If this is unsuccessful, reduce the pay at the end of the period.

- Red-circle the job and not the person.

- Eliminate the differential after a period such as a year or gradually over time.

A number of less common arrangements also exist. One, the adder, is a payment to the employee in quarterly installments of the difference between his or her rate and the maximum of the range. The employee is given 100 percent of the differential the first year, 75 percent the next year, and so on until there is no differential. The advantage of the adder is that the top rate for the job is made clear and both the person and the organization are aware of the exceptional and temporary character of the differential.

Another possible solution is a lump sum payment. For example, the employee may be paid the difference times 2080 hours and have his or her pay rate brought immediately into line.

Any solution to overpay involves questions of equity. Overpayment is usually not the fault of employees, and any reduction in pay will be seen as unfair by them. On the other hand, there is also the perception of equity by other employees, so some action is always called for. All the actions just described try to balance these two perceptions in arriving at an equitable solution. Failure to correct red-circle rates means that range maximums are meaningless; people may be paid more than their job and performance are worth to the organization; and organizational resources are being diverted into paying these rates rather than rewarding others' good performance.

ADMINISTRATION OF INDIVIDUAL PAY DETERMINATION

The pay rate of an individual reflects a number of considerations, of which performance is only one. Other variables found to influence pay are the person's pay history, present position in the pay range, and experience; the time since the last pay increase; the amount of that increase; pay relationship within the work area and other parts of the organization; labor-market conditions; the financial condition of the company; and of course the previous decisions regarding pay level and structure. The interaction of these forces determines whether a person receives an increase, and if so the amount of that increase.

Linking Pay to Performance

Almost all companies claim that performance is the primary variable in their determination of individual pay, but not many have a system that directly links pay to performance. However, it is becoming increasingly important for organizations to attempt to properly connect performance with pay, as employees expect that connection to be made.

Linking pay and performance is difficult at certain times. When inflation is running rampant, an organization may have to offer very large increases to be seen as rewarding merit and not just keeping its employees up with inflation. During times of uncertainty and market volatility, organizations may not increase their pay budgets enough to grant increases that are seen as rewarding. Even if an organization is committed to pay for performance, its employees are the ones who have to perceive the relationship. Most organizations are doing better at communicating "line of sight" to pay for performance in terms of expected behaviors and business outcomes.

Compression

One particularly sticky problem is that of wage compression. This occurs when new people are brought into a pay grade at the same, a higher, or even a somewhat lower rate than people currently employed in the same job. 15 This is most obvious in the case of new hires that are brought in at pay rates almost the same as those of employees who have been there a year or more. Rates for new hires are determined by the external labor market. Unless one pays that amount, the new employee will not accept the job offer. Current employees have their wages set by the internal labor market, which is an administrative decision. As we have noted, the particular pay rate for an individual is determined by a number of factors, of which the market is just one. The result can be that new hires make significantly more in relation to those already performing the job. This was especially true for new college hires in 1999 and 2000, when they were paid historically high rates.

Compression is also likely to occur with first-line supervisors of nonexempt employees who are paid overtime; with sales managers, whose sales staff can make more selling on commission than the manager; and with middle management, who are squeezed between top management and the increases given to entry-level employees. The last is very evident in government jurisdictions. All three examples differ somewhat from the case of new hires, in that they involve a hierarchy, and the perception of unfairness is related to an inadequate distance between organizational levels.

Solutions to compression depend upon what type it is and how serious it appears to management. One obvious solution is to ignore it. This is possible if people are moving rapidly and the problem is mostly one of timing. The person feeling the inequity can be told that it will disappear shortly. A second possible solution is to adjust the internal structure more completely to the external realities. This may be an expensive alternative but is necessary if the organization is experiencing turnover and employee dissatisfaction. In the three examples of supervisors in the paragraph above, the most likely solution would be a policy statement that a particular interval, say 15 percent, be maintained between levels. Rather than change the rate range for the supervisory jobs, however, organizations often pay this differential as a bonus based upon the pay of the subordinates.16

Integration of the Salary Structure and Individual Pay Determination

Changing the salary structure results in more money being spent on salaries. This then allows for pay adjustments for employees. But there needs to be some way for these two disparate events to come together. The vehicle for this is the budgeting process. On the salary structure side, estimate how much the structure should change and how much money will be required. This is usually done by a salary increase budget. The amount for this budget can be developed competitively by purchasing salary increase budget surveys. That money in turn becomes the organizational input data for individual pay determination. The question now is how to allocate the money provided by the salary structure adjustment.

Budget Allocation. The salary structure design decisions discussed in Chapter 12 and in this chapter provide a framework for deciding how the budgeted money is to be spent. Where a single-rate system is used, the pay adjustment is a general increase. The basic question then becomes one of timing. When should the general increase be granted? If an increase is given at the first of the budget period, then the percentage of the salary structure movement is the same as the general increase. But if the general increase is held off, the percentage can be larger and still fall within the budget. Remember, however, that this larger percentage is built into the next year's budget.

In organizations using an automatic-increase system, a change in the salary structure changes all steps in all grades. But there is an additional cost: the movement of people from one grade to the next. So, the total increase in the salary expense will be more than the increase in the salary structure. The exact difference depends on the timing of the step increases and on estimates of turnover. If all step increases are granted at one time then the impact is even, but if they are staggered by some criterion such as anniversary date, then the organization needs to prorate the increases depending on when they are granted. For instance, a 5 percent step increase given a person on July 1 is a 2.5 percent change for the year. But again, these adjustments increase the total wage bill beyond the cost of the salary structure adjustment. On the other hand, turnover tends to reduce the total salary expense since replacements are ordinarily hired at steps lower than those occupied by the people who left.

Decision Makers

In a merit-progression program the supervisor becomes a key person in the pay decision, for it is he or she who decides upon the performance of the individual. Thus, the pool of money available for pay adjustments is ordinarily controlled by the supervisor, to be dispensed within the guidelines provided by the organization. This supervisor must really believe in the value of a merit program for it to work. There are considerable pressures upon them not to allocate this money on the basis of merit. In brief, validating this decision in the minds of employees is difficult and may lead to feelings of inequity. In addition, supervisors are often much more concerned with cooperation than they are with outstanding performance.

An advantage of simpler individual pay determination is that the decision making can be more centralized and does not involve as much judgment. In this way consistency of treatment is maintained, which leads to feelings of equity. In an automatic-progression system Human Resources can make all the appropriate decisions and implement the program without having to coordinate their efforts with line management at all. This is convenient, but the program then becomes that of the Human Resources Department. Line management feels divorced from the compensation program, leaving them with the perception that they have little ability to motivate their employees.

Even if line management has a say in the determination of the exact amount people are to be paid, there are other decisions framing it and limiting its impact. These decisions start with the pay-level determination, the form and shape of the salary structure, and the design of individual pay rate determination.

SUMMARY

Organizations wish to pay for more than just the job that the employee does. Employees contribute both in terms of membership (staying on the job) and being productive while on the job. Both of these sets of contributions need to be rewarded by the organization. Salary structures deal with rewarding these sets of contributions by establishing rate ranges for jobs. This allows for variable pay rates for employees on the same job and/or in the same pay grade.

The breadth of the rate range (distance from top to bottom) is a matter of judgment for the business stakeholders and compensation experts designing the salary structure. Further, the decision is interrelated with other factors in the salary structure, namely the distance from top to bottom of the entire salary structure, the number of pay grades, and the amount of overlap between grades.

The design of rate ranges may vary from a structured set of steps with given percentage differentials, to an open range in which only the minimum, midpoint and maximum are defined. Picking the type of range depends largely on the factors that the organization wishes to reward. Step systems do a good job of rewarding membership and seniority. Open ranges allow the organization to more clearly recognize variable performance. There is an aspect of rewarding both in either case, so the choice is one of emphasis and not of kind.

In administering the movement of employees within rate ranges, the organization faces a number of problems. Recruitment in the labor market may require the organization to hire new employees at higher rates on the range. This in turn can lead to compression, as current employees are paid less than new employees. Keeping employees within the rate range is a constant problem. One of the most pervasive problems is keeping the focus of increases on performance; supervisors and employees alike are more comfortable with seniority increases. Last, while other aspects of compensation administration are often centralized in the hands of Human Resources, the determination of pay increases within grade must involve all supervisors in the organization.

Footnotes

1 J. G. March and H. A. Simon, Organizations (New York: John Wiley, 1963).

2 Bartol, K. and Locke, E. "Incentives and motivation," in Rynes, S. & Gerhart, B, Eds, Compensation in Organizations, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2000.

3 D. W. Belcher and T. J. Atchison, "Compensation for Work," in Handbook of Work, Organization, and Society, ed. R. Dubin (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1976).

4 D. Katz, "The Motivational Basis of Organizational Behavior," Behavioral Science, April 1964, pp. 131-33.

5 E. Jaques, Equitable Payment (New York: John Wiley, 1961)

7 L. A. Krefting and T. A. Mahoney, "Determining the Size of a Meaningful Pay Increase," Industrial Relations, 1977, pp. 83-93.

8 F. Krzystofiak, F. Newman, and L. Krefting, "Pay Meaning, Satisfaction, and Size of a Meaningful Pay Increase," Psychological Reports, 1982b, pp. 660-62.

9 U.S. Department of Labor, Salary Structure Characteristics in Large Firm, Bulletin no. 1417 (1963).

10 M. Haire, E. E. Ghiselli, and M. E. Gordon, A Psychological Study of Pay, Journal of Applied Psychology Monograph no. 636 (1967).

11 L. D. Dyer, D. P. Schwab, and J. A. Fossum, "Impacts of Pay on Employee Behaviors and Attitudes: An Update," Personnel Administrator, January 1978.

12 Purushothan, D. & Wilson, S., Building Pay Structures, Scottsdale, AZ. World at Work, 2004.

13 E. E. Lawler, Pay and Organizational Development (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1981).

14 Kovac, J. Green Circle/Red Circle, Scottsdale, AZ., World at Work, November 2005

15 Ladika, S. "Decompressing Pay" HR Magazine, Vol.50 #12, December 2005.

16 Kovac, J. Pay Compression, Scottsdale, AZ., World at Work, October 2005.

Internet Based Benefits & Compensation Administration

Thomas J. Atchison

David W. Belcher

David J. Thomsen

ERI Economic Research Institute

Copyright © 2000 -

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

HF5549.5.C67B45 1987 658.3'2 86-25494 ISBN 0-13-154790-9

Previously published under the title of Wage and Salary Administration.

The framework for this text was originally copyrighted in 1987, 1974, 1962, and 1955 by Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights were acquired by ERI in 2000 via reverted rights from the Belcher Scholarship Foundation and Thomas Atchison.

All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced for sale, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from ERI Economic Research Institute. Students may download and print chapters, graphs, and case studies from this text via an Internet browser for their personal use.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 0-13-154790-9 01

The ERI Distance Learning Center is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: www.learningmarket.org.