Chapter 16: Variable Pay Plans

Overview: This chapter discusses the various types of variable pay plans available, including bonuses, profit sharing, gainsharing, piecework and standard hour plans.

Corresponding course

75 Creating a Variable Pay Plan

INTRODUCTION

The basic ideas of variable pay have been around for many years under different labels. One of these labels was discussed in Chapter 14, that of Merit Pay. The focus of that approach is on performance, as measured through performance appraisal. A second and much older concept is that of the incentive pay plan. The focus in this case is on the motivational content, that of obtaining more effort from the employee. A third term used is that of payment for results. This is defined as: "a payment system under which money rewards vary with measured changes in performance according to predetermined rules."1 This type of compensation program makes the basic assumption that employees are interested in money and are willing to put forth more effort for more money. The important word in the above quotation is that of "vary." These types of plans vary the compensation depending upon some performance measure, ergo the term used as the title of this chapter, variable pay.

TRADITIONAL PAY

These concepts of variable pay are very different from the traditional compensation plan based upon payment for the job, or even personal competencies. In the traditional program, the employee who desires more compensation, or the supervisor who wishes to pay an employee more, has to somehow re-describe the job to be at a higher level in order for it to be "worth more." In contrast, variable pay plans allow the employee to earn more for improvement in the measures of results from current work, without having to change jobs or get themselves re-classified. However, this concept has drawbacks because the possibility of gain is tied to the possibility of loss. In variable pay plans some proportion of the employee’s pay is put "at risk." If they are successful, they will make more money, but if things go poorly, the employee's pay suffers. Not all people find this prospect comfortable. For instance, people who are "inner-directed" and feel they control their world find variable pay attractive. But those who are "other-directed" and feel that the world controls them are frightened by this type of program and therefore are not motivated by it.2

THE RISE OF VARIABLE PAY

Why has industry so embraced the idea of variable pay? There are a number of reasons. The first is an economic one. As noted in Chapter 3, "wages are sticky on the downside." When a company faces hard times, it is difficult or impossible to lower the base salaries of current employees. In this way salaries become a fixed cost and the only way the employer can lower costs is to lay off workers. Variable pay can soften this necessity to lay off large numbers of workers by lowering the compensation bill for all workers to some degree.

A second reason is contained in the "payment for results or performance" concept. If the company relates pay to the desired outcome, then this will increase the probability of obtaining that outcome. This may be through the employee working smarter, faster, or longer. As companies have laid-off employees, they have had to become leaner and more efficient. Being more productive with fewer people makes the promise of variable pay very attractive to companies today.

Third, as union influence has declined there has been significant growth in incentivizing the employee to not only do better at their job but also take an interest in how well the total organization is doing and make contributions to its overall success. There are some variable pay plans that focus mainly on trying to get the employee to join with management to create a successful company.

DO VARIABLE PAY PLANS WORK?

Variable pay plans elicit strong feelings. The growth in the number of plans has been impressive3 as has the amount of literature extolling the virtues of variable pay. Many proponents of variable pay plans believe that a fair day's work is not normally attainable without some proportion of pay being "at risk" because time based workers produce only about 50 to 60 percent of the output of variable pay workers.4 Despite all the hype, studies on the effectiveness of variable pay are not uniformly positive.5 However, the blame for these negative results is usually credited to poor installation and maintenance rather than shortcomings in the concept of variable pay.

There are those who have a more basic opposition to variable pay. Some opponents claim that performance is a function of the organization, of work and management practices, rather than employee effort; therefore incentives can't work and they cause more problems than they solve.6 In addition, employees vary in their interest and desire for variable pay, with a considerable divide between exempt and non-exempt employees.7

To understand why variable pay plans are so controversial, let's examine incentives and their use before turning to the characteristics of variable pay plans. We will discuss incentive contributions, compare them with two motivation models, look at the results of variable pay plans, and assess the prevalence of these plans.

Incentive Contributions

The wage system discussed in this book up to now, essentially pays people for the time they contribute. If we assume that the job is the major determinant of the wage, then it is a person's occupancy of that job for which the organization pays. Performance and any number of other factors may enter into the equation, but the time spent on the job is the primary consideration. To some degree, then, an organization wishing to attain increased performance has a choice of using a merit pay plan (see Chapter 14) or some form of variable pay. Both may reward performance, but the variable pay plans discussed in this chapter do so more directly. In addition, the effects of payment by results and payment by time on the organization's cost structure are different. Payment by results leads to variable labor costs, since these correlate directly to output. Payment by time makes labor costs fixed, since they are the same in any period, regardless of output.

Our model of the employment exchange specifies that it is contributions that lead to rewards; the question is the units in which performance is determined. Payment on the basis of time allows for a large number of unspecified contributions to be included. Payment for output requires that contributions be specific and produce measurable results before they are recognized as contributions.

In practice, however, variable pay plans often turn out to be payment for one contribution – effort; other contributions required by the organization are often ignored. The measure of distribution does not have to be either output or time. These two can more reasonably be viewed as the two ends of a continuum on which various wage systems can be placed. At one end is time with a system of automatic rate adjustment. At the other end is a piece-rate system, which pays a set amount for each unit produced. Other systems would fall at various places in between. This continuum is illustrated in Figure 16-1. Where an organization should fall along this scale is a matter of many factors.

Factors in Determining Pay Plans

The work itself is a major determinant of whether to pay for time or output. The work characteristics to consider include (1) measurability of output; (2) the relationship between effort and output; (3) the degree of standardization; (4) requirements for quality as well as quantity; and (5) competitive conditions, which make it imperative that unit labor costs be well defined, fixed, and known before production.

General expectations are also very important. Community attitudes and the expectations of employees, both as individuals and as expressed through their union, affect attempts to install a variable pay plan and certainly its chances of success.

Technological considerations may, of course, enter into the decision. To the degree that machines set the pace for the work, the employee loses control over determining the number of units that will be produced. The ability to change output through increased effort is critical in variable pay plans. Also, variable pay plans are more likely to be successful in industries with a stable technology than in those undergoing continual technological change.

The decision to pay for output instead of time is partially based upon the rational factors just discussed and is also partially a matter of faith. If an organization is convinced that incentives are the way to go, then a way will be found to apply incentives to the work. The varieties of variable pay plans and the kinds of contributions are so numerous that desire is more important than a precise fit of job and variable standards.

Variable Pay Plans and the Motivation Models

Since organizations believe that variable pay plans motivate performance, the evidence should be reviewed. Research shows that this belief has a foundation: variable pay plans can increase performance above that attained in a fixed pay plan. But as noted above, the result is not always higher performance. In fact, numerous studies have shown that variable pay plans can also result in restriction of output and cause employee-relations problems. It has also been shown that the different kinds of variable pay plans produce different results. Thus, it seems useful to examine variable pay plans in terms of the performance-motivation and membership models outlined in Chapter 4.

The Performance-Motivation Model. According to this model, for a compensation plan to motivate performance, employees must:

- Believe that good performance will lead to more pay

- Want more pay

- Not believe that good performance will lead to negative consequences

- See that other desired rewards besides pay result from good performance

- Believe that their efforts do lead to improved performance

Although the model specifies that the relationship among these variables is multiplicative, the first variable remains the most important.

Variable pay plans do foster the belief that good performance leads to more pay. Some plans do this better than others. Specifically, plans that relate the individual's pay to their output, do better than plans applied to groups or other larger units. Plans based on objective standards and measurements create a stronger belief in the performance-pay relationship than plans based on less objective standards. With plans involving less objective standards, the belief is based in part on the employee's confidence that the measurements do reflect their own performance.

Since people attach differing values to pay, the second condition, desiring more pay, is variable. If employees want more pay and nothing about the plan serves to reduce its importance to them, this part of the model is met. If, however, a variable pay plan is applied to employees who don't value more pay or who don't want pay based on performance, it is not.

The belief that negative consequences will result from good performance is quite possible under variable pay plans. It has been shown that employees can believe that performance pay will be cut if they produce too much. Other employee fears can also be anticipated: social rejection by peers, working themselves out of a job, or even getting fired if they fail to meet the standard. Thus, in some plans it is quite possible that the perceived negative consequences could offset the perceived positive consequences. A major negative consequence is the competitiveness inspired by variable pay plans. Where cooperation, not competition, is required, a variable pay plan can lead to a variety of dysfunctional employee behaviors.

The belief that desired rewards will result from good performance is more likely to appear when the competitive nature of the plan is minimized. In some plans, good performance is likely to result in social acceptance, esteem, respect, and feelings of achievement. If some employees feel that they benefit from another's good performance and it becomes the norm of the group to perform well, then the possibilities of good performance are increased.

Employee perceptions about their contributions to the organization may be the weakest link in variable pay plans. If employees feel that the performance measured is affected by so many things beyond their control that their efforts have little effect, this belief in the contribution-reward connection will be weak. If employees feel that the performance measure does not reflect a number of contributions that they make and that they feel the organization needs, the belief is likewise weakened. If the variable plan is based on such a limited conception of employee contributions that employees believe that it reflects neither the contributions they make nor those that the organization really requires, not only will the variable pay plan not work, it may weaken membership motivation because of resentment.

The Membership Model. If variable pay plans work by creating or confirming beliefs, they can also affect the beliefs and perceptions that form the basis of membership motivation. If the variable pay plan signals employees that more of the rewards they want are available in this employment exchange in return for the contributions they want to make, their commitment to the exchange is likely to increase. If, however, the plan signals that:

- additional money is the only reward available for increased performance and they don't value more money then they will perceive that good performance will not bring other rewards they do want

- only those contributions resulting in the measured performance lead to more rewards, but they do not want to provide more of those contributions, then the rewards will have a limited effect

- the contributions they do wish to increase are not going to result in higher rewards, they may be less motivated

Any of these may result in the employee's commitment to the employment exchange being significantly depressed. In fact, the employee may seek an employment exchange that meshes more closely with their contribution-reward desires.

Thus, attempts to improve performance motivation may weaken membership motivation. This is an example of the dilemmas faced by organizations in compensation administration. Fortunately, it is usually possible to treat different employee groups differently in matters of pay.

Results of Variable Pay Plans

Most reports of experience with variable pay plans suggest that pay incentives result in greater output per hour worked, lower unit costs, and higher employee earnings. Typically, these reports come from companies experienced with variable pay plans that do not attempt to determine the source of change or to compare results of variable pay workers with those of a control group. When variable pay plans are installed, many changes are made in the conditions of work, and if no effort is made to determine the effects of each, the changes observed may be due to something other than the variable pay plan. It is quite possible, for example, that the results obtained are attributable to changed management practices employed as a prerequisite to installation of a variable pay plan.8

Reports of variable pay plan results often cite employee earnings increases of 10 to 70 percent and cost decreases of 25 to 65 percent. Although this implies that the observed results are attributable to the variable pay plan, no attempt was made to determine whether the source of improvement was better management, increased employee effort, or other changes accompanying installation.

A review of variable pay plan effectiveness claims that the results are impressive and greater than that achieved by other Human Resource programs. These productivity gains are estimated to be in the range of 10 to 20 percent.9 Locke and associates examined experiments that compared the effects of individual variable plans with those of time-based pay plans. The average increase in performance was 30 percent, with a range of 3 to 49 percent.10

Under a variable pay plan, increased productivity should result in higher salaries for employees.

DIMENSIONS OF VARIABLE PAY PLANS

To be effective a variable pay plan needs to fit the circumstances of the organization. The great variety of variable pay plans that are possible can be classified by several variables, specifically the level of aggregation, the performance definition, and the reward determination method. This section examines these variables, and the following section will look at the necessary considerations in designing a variable pay plan.

Level of Aggregation

The level of aggregation defines the unit for which performance or output will be determined. In turn, this defines the unit that will receive the organization's reward. Three levels of aggregation are usually defined — the individual, the group, and the organization.

Individual Level Variable Pay Plans. This is the most popular form of variable pay plan. In this type of plan each person's output or performance is measured and the rewards the person receives are based upon this measurement. Clearly this is the type of variable pay plan most likely to establish a clear performance-reward relationship in the mind of the employee. The purpose of the plan is to increase the pace of work, or the effort the individual is willing to contribute, to receive higher rewards. The classic example of this type of plan is a piecework system, wherein the employee is paid a set amount for each unit of production.11 The organization expects to receive more output than it would if the employee were paid under a time-based system. In addition, the organization can easily track the labor cost associated with each unit of output.

One assumption of these plans is that the employee is an independent operator, that he or she alone can carry out all the activities required to achieve the performance measure. In this way, performance is a function of the employee's effort. The performance standard must be clearly defined and measurable if such a plan is to be useful. Also, the job must be relatively stable: the output required from the job should be consistent, and the inputs to the job should arrive in such a way that the employee can work continuously.

Group Level Variable Pay Plans. Where it is impossible to relate output to an individual employee's efforts it may be possible to relate it to the efforts of the work group. If, in addition, cooperation is required to produce the desired output, then a group variable plan may be the best alternative. Interdependence of work, then, is a major reason for choosing a group plan over an individual one. A group variable plan can reward things that are very different from what an individual plan rewards, in particular: cooperation, teamwork, and coordination of activities. Where these are highly valued, a group plan is most appropriate. As organizations become more complex and the production process more continuous, group variable pay plans have become more popular.

Group plans are also useful where performance standards and measures cannot be defined objectively. In a group setting, variations tend to average out, so no one gets as hurt by any random variation or lack of continuity. Almost any individual plan can be adapted to a group setting. Thus, the focus in group plans is still a higher level of effort.

The primary disadvantage of the group plan is that it weakens the relationship between the individual's effort and performance. Where there is likely to be wide variation in the efforts of group members, a group incentive may lead to more intra-group conflict than cooperation. In group plans it is also more difficult to monitor performance standards and measures. Finally, group norms play an expanded role, both positive and negative, in group plans. They are stronger and more controlling on the individual. Where the group norms are congruent with management's goals, this is a plus; but where the two differ, it can harm the chances of success of the variable plan.

Plant and Organization-Wide Variable Pay Plans. Organization-wide plans have gained in popularity, more so than other variable pay plans. Some such plans, such as the Scanlon plan, have been around for a while, but new kinds of plans are being developed, too.12 Organization-wide variable pay plans are now generally called gainsharing plans.13

Organization-wide plans differ significantly from individual plans by rewarding different things. As indicated, most individual and group plans attempt to increase effort. Most organization-wide plans, however, reward an increase in organization-wide outcomes that directly affect the cost and/or profit picture of the organization. Usually, these plans reward increases in productivity of the plant or organization as measured by reduction of organizational costs, in comparison with some measured "normal" cost. Or they may reward increased output when there are the same or fewer inputs utilized.

A major feature of organization-wide variable pay plans is a change in the relationship between management on the one hand and employees on the other. Rather than the traditional adversarial relationship between the two, most organization-wide plans require a high degree of cooperation. This is because both groups must focus on the desired cost savings and listen to the other party. All this requires a degree of trust that is hard to achieve in American labor relations. Failures of the Scanlon Plan have been attributed most often to the inability of management to take employee input seriously.14

Profit Sharing. Profit sharing is another popular organization-wide program that is often classified as a gainsharing plan. This type of plan can be made much simpler than a cost-savings plan. It also doesn't require the revolution in employee-management relationships that cost-savings plans do. With profit sharing, management hopes to change employee attitudes toward the organization without a concomitant change in managerial attitudes toward the employee. The idea behind profit sharing is to instill in the employee a sense of partnership with the organization. But most plans go beyond this and use profit sharing as a way to keep valuable employees and to encourage thrift in employees.

Clearly the relationship between effort and performance becomes very tenuous in any organization-wide variable plan. Even if the performance (profit or cost savings) and the reward (an amount of the profit or savings based on salary) are clear, their connection with what the employee does every day is not clear. In fact, most organization-wide plans fit the membership model better than they do the performance-motivation model.

This enhanced membership motivation appears to be the greatest strength of profit sharing. The profit-sharing objective of instilling a sense of partnership is met to the extent that employees want to continue their membership and to make the additional contributions that enhanced membership implies. Improved performance may result not because employees see a performance-reward relationship but because they want to broaden and deepen the employment exchange by increasing their contributions in return for more intrinsic and perhaps extrinsic rewards.

The Definition of Performance

Properly defining performance is probably the most important step in establishing any variable pay plan. It tells the employee what output or behavior the organization considers important enough to reward – that is, to spend its money on. The point is that the employee's attention is directed to accomplishing a particular objective, or group of objectives, at the expense of other objectives that might also be needed to accomplish the job. So, the definition of performance should be complete, or the organization will not obtain the outcomes it needs from its employees. This section will examine the range of factors that is often used as the definition of performance in variable pay plans.

Output. The most common definition of performance, and in many ways the best, is the intended output of the job. In some situations, this can be made an explicitly measurable item, such as the number of electronic assemblies produced. In many jobs in organizations, however, it is hard either to define exactly the output desired or to measure that output. A variable pay plan is not well suited to these unquantifiable circumstances.

The most common variable plan that uses an output measure is piecework. In this plan, a set reward value is attached to each unit of output; the employee's pay is that value times the number of units produced. This plan clearly connects performance and reward and allows the employees to know at all times exactly how much reward they will be receiving. Since the piecework system emphasizes quantity, quality can be a problem unless it is also built into the determination of units produced.

Straight piecework can intimidate employees because it places them under considerable pressure to produce, which they may have difficulty doing consistently. Also, since failure to meet the standard may cause the employee to earn below the minimum wage, most piecework plans establish a minimum standard for a set wage and pay a premium for units produced above that minimum. Employees who regularly do not make the standard should be reviewed to see if they are properly placed.

Time. An alternative to output is time required to complete a task. Amount of production and amount of time are two variables that are always considered together in individual variable plans. In piecework, the amount of production is the measure put before the employee, and time is used to determine the value of the output. In time-based rates, the expected production is stated as a function of the time taken to produce that output, so the output is expressed as a function of time and not money.

The most common form of a time rate individual incentive is the standard-hour plan.15 As in piecework, the employee is paid according to output. However, in the standard hour plan a standard time is allowed to complete a job and the employee is paid a set amount for the job if completed within that time. For instance, an auto mechanic may be assigned to tune an automobile, a task for which the standard time is two hours. If the mechanic completes the task in an hour and a half, he or she is paid for two hours. If the job takes two and a half hours, the mechanic is paid for that time. Continually failing to make the standard time would result in examination of either the time standard or the employee.

Another form of time rate is measured daywork.16 Under this plan, formal production standards are determined for the job, and employee performance is judged relative to those standards. Evaluation is done at least quarterly, and the employees’ pay rates may be adjusted according to how well they have performed in comparison with the standard. This plan looks very much like the merit pay system discussed in Chapter 14. The real differences are in the measured daywork formality of production standards and shorter period of performance review. However, with the measured daywork plan, pay rates may go down as well as up. Measured daywork is advantageous where there are numerous non-standardized conditions in the work that make judgment of performance more important. Sometimes measured daywork utilizes the time standards but does not include the incentive feature.

Multiple Performance Dimensions. Any variable pay plan is designed to focus the employee on particular desired outcomes or activities. The effect of this is that any job dimensions not included in the definition of performance are not as likely to be performed. Thus, it is important to include all important job dimensions in the performance definition. A single dimension, such as units produced in a piecework plan, is appealing in terms of simplicity and clear performance-reward connections but is often dysfunctional when it comes to genuine productivity. The clearest example of this is the problem of quality in a piecework plan. If the number of units is the only performance standard, the employee is encouraged to turn out a lot of units, but the units will likely be substandard.

Many variable pay plans, then, employ multiple performance definitions, and the question becomes how to combine them. The simplest way, if possible, is to use a composite score. The values of the various performance variables are added together. This in turn leads to the question of the weight each variable is accorded. This process is much like the use of a number of compensable factors in job evaluation (see Chapter 11). A second method is the multiple-hurdle approach, in which a minimum level must be reached on each performance dimension before any incentive is paid. A third approach is a series of mini-variable pay plans, one for each performance dimension.

Reward Determination

A major assumption of the performance-motivation model is that the person must desire the reward being offered. Since money is considered the most desired reward, it is far and away the most important reward offered in variable pay plans. The assumption behind any variable pay plan is the high value of money to the employee. Although there are few employees who would claim that money is unimportant, the degree to which money is important to people varies with their circumstances. So, variable pay plans are likely to be of major importance to only some employees. Two aspects of money need to be considered by the administrator of a variable pay plan – when and how much of it is granted.

Timing. We have seen that the reward may be granted anywhere from immediately after the accomplishment to many years later. From a motivational standpoint, the closer the reward is to the desired performance the stronger the motivational value. This is because the person can more easily attribute the reward to a particular performance. Variable pay plans vary greatly in their timing of the reward. Those such as piecework make the connection every payday. Others, such as bonus plans, may grant the reward quarterly or semiannually. Under deferred plans, it may be years before the person receives any value.

Amount. The reward must be perceived as worth the additional effort. A variable pay plan that requires considerable effort for a small amount of extra money will probably not lead to extra effort. Where the variable pay plan is an adjunct to the regular wage, the amount possible to receive under the plan must be a large enough percentage of base pay to entice the person to put forth extra effort. Again, the amount or percentage that will be perceived as significant varies with the person.17

Non-Financial Rewards. Not all variable pay plans focus on money as the reward. Time can be a significant reward to many people. Variable pay plans can provide time off the job as well as more pay. To many people in our society, defining what needs to be done and then letting the person complete it in whatever time is comfortable provides not only free time but a sense of freedom as well.

TYPES OF VARIABLE PAY PLANS

So far in this chapter we have described a number of variable pay plans, mostly in the previous section. Piecework and various forms of pay for time were covered. In addition, gainsharing and profit sharing were mentioned. In this section these two are covered more thoroughly and a new topic, bonuses, will start the section. These three represent the most common forms of variable pay plans in use today.

Bonuses

A bonus is a one-time payment to the employee that is not built into his or her pay rate. The basis of the bonus may be any performance desired by the organization, and the payment schedule can be designed like that of the standard hour or measured daywork. But a bonus system can be used in much broader circumstances. An advantage to a bonus is that it may be a reward for any behavior or outcome deemed important to the organization; it does not have to cover all relevant parts of the job. An example of this is a series of programs designed to reduce absenteeism in organizations through the use of behavior-modification principles.18

Some organizations have adapted their merit pay plan to a bonus plan. The base pay of all employees stays the same or increases by a cost-of-living factor. Then the results of the merit pay plan are converted into bonuses that are distributed in various ways, from a lump sum to an addition to each paycheck. The point, however, is that the bonus is just for the current period and not built into the base pay.

Besides performance bonuses there are four other types of bonuses used in organizations:

- Sign-On. This type of bonus is granted at the beginning of service to a new hire, as an incentive to join the organization. This usually involves hard-to-hire skills.

- Referral. Current employees are given a bonus for recommending someone who in turn accepts a job with the organization.

- Spot. This is a bonus for some behavior or accomplishment that is given at the time of the action. Supervisors are often empowered to grant this type of bonus without a layered review process.

- Retention. This type of bonus is given to an employee who has stayed with the organization for an extended period or who the organization wishes to retain because of their knowledge or skill.

The use of bonuses is almost universal for executives and managers. It is also popular in sales compensation. However, bonuses have been used less in recent years, particularly the use of spot bonuses. However, in the financial field, bonuses are still a major part of compensation for most high-level employees.

Some variable pay plans avoid any involvement with the pay system by developing contests in which employees receive prizes of value to them. These prizes can range from merchandise to vacation trips. Of course, the prize must be something the recipient desires. Otherwise, there is no incentive to perform. Incentives such as this can also be dysfunctional if the reward is for something that is peripheral to the job. The focus on the contest may remove attention from the basic purpose of the job.

Gainsharing

This approach rewards outcomes that are direct measures of the success of the organization as opposed to the success of the individual employee. As we have noted, a gainsharing plan is a favorite type of organization-wide variable pay plan. The purpose of gainsharing is to tie the employee to the performance measures by which top management is judged and by which society defines a successful organization. Although clear performance-reward connections can be made in these circumstances, it is difficult to make a performance-effort connection.

A number of different performance measures can be used in gainsharing, but all share a common dimension: a baseline standard must be established to determine where the organization is "at the present time." The value of improvements in future measures of performance is then shared with the employees. One set of these performance definitions rewards reductions in costs, another rewards improvement in productivity.

The most popular early gainsharing plan is the Scanlon Plan.19 In this plan employees are paid a bonus if costs remain below pre-established standards. The standards have been set by studies of past cost averages. Ways to reduce costs are developed by a series of committees throughout the organization and a plant-wide screening committee that reviews and implements changes. Although Scanlon developed this plan in 1937, these committees look much like the quality control circles that are used in industry today. The Scanlon Plan is built on a philosophy of labor-management cooperation that was uncommon in its day and still is not the norm of American industrial relations.

The Scanlon Plan is not the only organization-wide plan, but it is the best known. Others that have been successful in the United States include the Rucker Share-of-Production, Kaiser, and Nunn-Bush plans. A second generation plan is Improshare20 and the most recent plans to be developed are called Goalsharing.21 Although all these plans differ in details, all rely on a definition of productivity improvements wholly measured by some time period and all pay out bonuses for savings gained by the company. Further, most depend upon labor-management cooperation that represents a change in the relationship between management and labor.

Profit Sharing

A further option for tying employees to the economic success of the organization is to grant them a share of the profits of the organization. Obviously, this type of incentive is useful only in a for-profit organization. Profit sharing may be the oldest form of an organization-wide variable pay plan. They were installed to deal with employee's grievances over low salaries and to combat the feelings that organizations made huge profits but paid workers very little of the gains. Later the idea of aligning worker and management goals appeared.

Increased production has been cited as one of the goals of profit sharing, and reported results include increased efficiency and lower costs. Many early reports of profit sharing results attributed large increases in production to such plans. Other reports have found that profit sharing companies are more successful financially than non-profit sharing companies but are more careful in attributing the difference to profit sharing.22 Profit sharing is popular for organizations, from both a practical standpoint and a philosophical one. Management often believes that having the employee focus on profits is useful and will lead to higher organizational profits. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), variations in profits, and defined contribution plans or 401(k) have changed the way in which profit sharing operates. Much of the literature today equates profit sharing with retirement plans as organizations contribute to their 401(k) plan on the basis of organizational profits. This tends to move profit sharing from a variable pay factor to a benefit.

Profit sharing plans are typically differentiated based on when profit shares are distributed. Cash plans (known also as current-distribution plans) pay out profit shares at regular intervals. Deferred plans put the profits to be distributed in the hands of a trustee, and distribution is delayed until some event occurs. This type of plan is most often tied into a retirement system. Combination plans distribute a part of the current profits and defer the rest.

Profit sharing plans vary widely in provisions concerning organization contributions, employee allocation, eligibility requirements, payout provisions, and other administrative details. Two-thirds of the plans define the contribution of the organization by a formula; in the others the board of directors determines the amount. Most formulas specify a straight percentage of before-tax profit after any commitments are fulfilled for stockholders and reserves. The amounts allocated to employees, or their accounts, performance, or responsibility. In most plans all full-time employees are eligible immediately or after a short waiting period, but a substantial minority excludes union employees or is limited to specific employee groups. Payout provisions are usually determined by plan designation (cash, deferred, or combination), but deferred and combination plans are increasingly incorporating vesting provisions and payout under a wide variety of circumstances.

Our discussion of profit sharing suggests that it does not closely fit the performance-motivation model. Profits are influenced by so many variables that it is very difficult for an individual to feel that his or her contributions have organization-wide results. Thus, it is difficult for employees to believe that their profit share is related to their performance. It may be possible for small organizations with cash plans and continuous communication efforts to maintain their employees' belief in the performance-reward relationship, but such a belief is vulnerable to any reduction in profits that occurs while the employee is maintaining his or her performance level. Larger organizations with cash plans are less likely to be able to foster this belief in the first place and may be even more vulnerable to changing circumstances. Deferred plans involve the additional hurdle that payment is delayed, often for years. Under such plans employee belief in the performance-reward relationship may be impossible, even in small organizations.

On the other hand, profit sharing may closely fit the membership-motivation model even in large organizations, at least for certain groups of employees. Two things serve to increase both the numerator and the denominator of the membership-motivation model: (1) the promise to provide additional economic rewards when profits of the organization permit it, and (2) the implied acceptance of all employee contributions that will advance the profit goal. In this way employees may increase their commitment to the organization.

DESIGN OF VARIABLE PAY PLANS

In a previous section, we discussed the two basic parts of a variable pay plan: performance definition and reward. In this section we discuss how these two are put together into an operating plan. Specifically, the jobs to be included, relating performance to reward, and the administration and control of variable pay plans are examined.

Organizational Strategy

The first area of consideration in designing a variable pay plan is the organization's strategy. The objectives and culture of the organization will greatly influence the type of plan that is appropriate. There have been numerous examples of this in what we have thus far discussed in this chapter. A good example of this is the different types of plans that would be appropriate depending upon the need and culture of competition vs. cooperation within the organization.

The external environment also influences the type of variable pay plan that is appropriate. A very competitive industry creates an internal environment of stress and pressure that is reflected in the type of plan that would work. The purpose of the organization is also a factor. Organizations in social service industries would again focus more on cooperative plans than competitive ones.

Organizational Characteristics. The size of the organization may affect the chances of success of variable pay plans. A large organization can typically make the administrative commitment required to support an individual plan. Organization-wide plans may be more effective in smaller organizations where the connection between effort and performance may be clearer. Also involved is the proportion of total costs represented by labor costs. If labor costs are a high proportion of total costs, placing labor costs on a variable-cost basis is worth considerable effort. But if labor costs are a small proportion of total costs, variable pay plans will appear less attractive to management.

Management Attitudes. The type of management constitutes a major variable in the success of variable pay plans. Unless management is committed to maintaining the relationship between performance and pay and backs this commitment with the necessary administrative expenditures and organization of work, an individual variable plan can fail or become obsolete very quickly. Management attitudes will depend in part on the nature of competition in the industry and on business conditions, but the real variable is the trust management has in employees to guide and direct their own activities. This is true of both individual and organization-wide variable pay plans.

Relationships with employees, formal or informal, also determine the kind of variable pay plan, if any, that is feasible. A hostile relationship argues against any variable pay plan, because it will create an atmosphere of controversy. A formal, arms-length relationship suggests limiting incentive coverage to situations where sufficient objectivity can be achieved to preclude disagreement. If, however, the relationship is characterized by mutual respect and trust, variable pay plans dictated by technical conditions may be employed. For example, a gainsharing plan based on imperfect measurement may be used if the work requires it.

Jobs to Be Included

Not all people nor all jobs should be placed under a variable pay plan. Jobs in particular vary in appropriateness for use in variable pay plans. Further, the diversity of variable pay plans and the inconsistencies in effectiveness of those being used suggest that there are conditions under which a particular plan is applicable. There are certain conditions that produce success or failure for variable pay plans in general, but the job itself dictates whether or not it is a good candidate for a variable pay plan.

Job Conditions. The kind of work being performed is a major contributing factor in choosing which variable plan, if any, is the most applicable. A plan suited to highly repetitive, standardized, short-cycle manual operations is unlikely to fit a less structured work environment. Highly variable, non-standardized work may make incentives unworkable.

The major job variables that need to be examined in determining the applicability of incentives are (1) standardization of the job, (2) repetitiveness of the operations, (3) rate of change in operations, methods, and materials, (4) control of the work pace, and (5) measurability of job outcomes. If these variables are applied to a scale such as figure 16-1, then the more each is true for the job, the more individual variable pay plans that focus on job outcomes, such as piecework or standard-hour plans, are appropriate. If these conditions are not met and variability is introduced, group- or organization-wide plans, such as gainsharing, are more appropriate. These types of plans can smooth out the variations that occur in jobs that fall between the two extremes, illustrated in figure 16-2.

At the other end of the scale are jobs that are largely inappropriate for the use of incentives because of their lack of standardization and repetitiveness, frequent changes in methods, lack of worker control, and difficulty in measurement.

Most organizations have jobs that fall into all of these categories. Thus, an organization desiring to place all or most employees on incentives may find that a plant-wide plan is most feasible. Some organizations, because of the value of incentives, choose to invest a great deal of time in developing an individualized variable plan that takes into consideration their variable situation, but most choose to install a number of different plans, each geared to a segment of the organization, or an organization-wide plan.

Workers are often required to cooperate rather than compete with one another, and on a larger scale, with other organizational units. Such requirements, which are becoming the norm in complex organizations, argue against individual variable pay plans and in favor of group and organization-wide plans. Obtaining cooperation among interdependent workers and among organizational units is difficult under the best conditions and cannot be expected when the reward system encourages competition.

Variable Pay Plan Applicability.

There is a tendency to think of variable pay plans as being applicable primarily to direct production jobs or on the other extreme, executives, while merit pay plans are for other employees. This tendency applies primarily when considering individual and small-group incentives, rather than plant-wide or organization-wide plans, which ordinarily cover all employees.

The fact is, however, that individual and small-group variable pay plans are applied to almost all varieties of work. What is required is a willingness to engage in the expense and administration required to make the program work. From this standpoint, there is scarcely any job that someone has not successfully measured and applied a reasonably successful variable pay plan to.

The premise for this reasoning may be simply stated. All tasks, jobs, or functions must have a purpose. Better performance of this purpose is worth money to the organization. Devising a yardstick to measure this improved performance will therefore permit rewarding the individual or group who achieves it.

The general approach in all these applications of variable pay plans has been: (1) identifying measurable work as a yardstick of performance, (2) setting standards on the basis of this yardstick, (3) measuring performance against these standards, and (4) providing extra pay for performance above the set standard. It has been found in all of these applications that certain aspects of work results can be measured.

The widely varied applications of variable pay plans show that with diligence and ingenuity it is possible to find and measure aspects of work. It is useful to remember that the kind of behavior measured is the kind of behavior that people exhibit. Thus, organizations must be certain that variable pay plans are based on measures of output that they require rather than merely on those that can be measured. If what is measured is related only peripherally to organization goals and if what is not measured remains undone and neglected by employees, the variable pay plan impedes attainment of organization goals.

Relation of Performance to Reward

The central imperative in variable pay is that the person being paid understands that there are particular outcomes or behaviors, when compared successfully with the performance standard, that will lead to a specified reward. In this section we will cover the development of this relationship.

To develop this relationship, the performance standard must be clearly stated and the ratio between it and the reward delineated.

Setting Performance Standards. A variable pay plan must contain a clear performance standard. As we have seen, several definitions of performance are used in variable pay plans. These include the output of the job, the time taken to complete a task, the efficiency with which the job or organization operates, and the profit derived from the operation of the organization.

Setting performance standards in terms of outputs would seem the best choice since it taps the purpose of the job. But in many jobs, it is difficult or impossible to quantify the output. Further, output can be defined in terms of the number of units, the quality of those units, and/or the time taken to complete the units.

The most common way of determining a performance standard for production jobs is to conduct a time and motion study. This technique estimates the time normally required to produce a unit. In turn, a study of the job in operation is made. This study looks at the exact motions and time required to perform the task. Thus, each activity or element that goes into producing a unit is timed, and a total time is developed under which a normal worker working at a normal pace would complete a unit of production.23 The equitable relationship between the unit of production and pay can then be derived by finding the market rate for the job or through bargaining. The focus of a time and motion study can be either the output or the time taken to complete the task. Thus, both piecework and standard-hour variable pay plans tend to use this technique.

Non-production jobs can also be paid under a variable pay plan based upon outputs. Sales jobs are a case in point: the salesperson is paid based on sales volume. Regardless of the job, the major requirement of setting performance standards is to define the value of a unit of production or performance. In order to do this, there must be some idea of a normal output and an equitable wage for achieving that output.

Variable pay plans focusing on efficiency or cost reduction involve defining a standard or normal cost and then rewarding employees that achieve the goal at less than this standard cost. The cost definition varies with the plan. In a Scanlon Plan the typical cost standard is labor costs as a percentage of sales. The Rucker Plan uses value added to goods during manufacture for each dollar of payroll costs measured by the difference between sales income from goods produced and the costs of materials, supplies, and services consumed in production. In Improshare, the focus is on the hours saved in producing a given output. Production standards are developed from past production records.

Profits are a clear-cut measure, but as a performance standard in a profit sharing plan they require two decisions. The first is to set the percentage of the profits that will go into the profit sharing plan in each time period. This percentage can be fixed, such as 10 percent, or established anew for each period by management decision. The second decision is the proportion of the total allocation that each person receives (distribution). This is ordinarily done by calculating an employee's base pay as a percentage of total payroll and giving the employee that percentage of the total profit sharing allocation.

Proportion of Earnings. Variable pay plans can range from being the basis for all of the employee's pay to being an insignificant percentage of it. In a straight piecework plan, the employee is paid for the number of units produced. There is no guarantee of how much the employee will make in a time period; that is up to the employee. A production line worker who is paid a certain amount for every 100 units would be an example. At the other extreme might be a profit sharing plan that provides no additional money, beyond base pay, to the employees in a year in which the organization does not make a profit. Clearly, in these two cases, the importance of the variable pay plan to the employee and its motivational effect is very different.

Both of these situations are likely to be unacceptable to the employee, but for different reasons. The straight variable plan makes the employee feel insecure. In the second case, there is supposed to be an incentive, but none is forthcoming, or it is so small that it means nothing. The employee feels cheated. The lessons from this are that some guarantees should be built into the variable plan on the one hand, and the variable plan should be a significant proportion of the employee's total pay on the other.

Rather than a straight variable plan, most plans contain a guaranteed base pay. This is usually the market rate or some proportion of the job's market rate. This guarantee is associated with an output standard that matches the guaranteed rate. The variable plan then really operates only if the employee exceeds the performance standard; for all time periods in which he or she does not "meet standard," the pay is the base guaranteed pay. In this way, employees are protected from circumstances beyond their control that limit production in a particular period. If an employee continually fails to meet standard, management must decide whether the standard is incorrect or whether the employee is not capable of performing the job.

As we have seen, for a reward to be of value to a person, it must be perceived as significant enough to expend effort on. Ordinarily, an incentive that yields a small proportion of the employee's earnings or a plan in which the probability of attaining the reward is low does not energize the employee to expend effort. Thus, it is unlikely that the organization will attain the performance it desires. One exception may be a spot bonus that rewards a very specific behavior that is an out-of-the-ordinary outcome of the job.

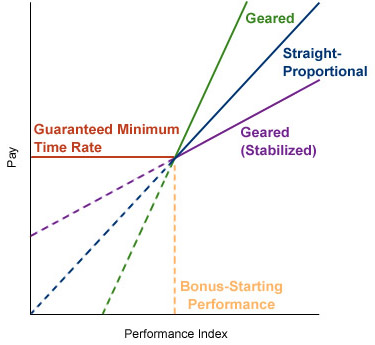

Performance-Reward Ratio. Basic to the performance-reward connection is the ratio of reward to performance. This ratio can take a number of forms. The most common is the straight-proportional ratio. This is the type used in piecework and standard-hour plans. It provides a one-for-one proportion between performance and reward. A second possibility is the geared ratio. In this case the ratio of reward to performance units varies at different levels of production. The proportional change may be less or more than the proportional change in output. The possibilities are illustrated in Figure 16-3. Note that this illustration assumes that there is a base rate of production and reward after which the variable pay system takes hold.

(Source: Payment by Results, International Labour Office, Geneva, 1984, p. 11.)

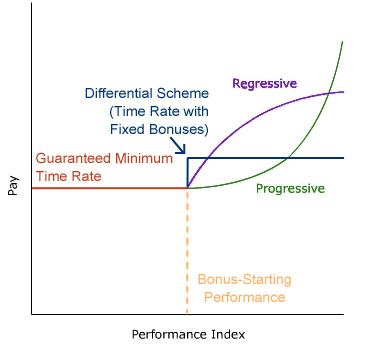

These three examples do not exhaust the types of performance-reward ratio. Three more, based on the geared ratio, are illustrated in Figure 16-4.

(Source: Payment by Results, International Labour Office, Geneva, 1984, p. 12.)

In a progressive ratio the reward increases with higher production. This type of system is most likely to be useful where higher levels of production become increasingly difficult to achieve. A regressive ratio is the opposite: higher levels of production lead to less proportionate reward. This may be appropriate where higher levels require help of others in the organization to achieve them. The final ratio is not really a ratio but a fixed amount if a standard is exceeded. This arrangement is often found in a fixed bonus system.

Positive Reinforcement Plans. To some degree all variable pay plans are based upon the principles of behavior modification. Some organizations, however, have developed variable pay plans that specifically use positive reinforcement. A major use of these programs has been to reduce absenteeism. Although praise is the basic ingredient in many positive reinforcement plans, monetary rewards may also be used.

Administration and Control

Careful attention to variable pay policies and procedures is a necessary prerequisite for the installation and successful operation of any variable pay plan. Wide participation in the development of these policies and procedures, including union-management negotiation, also increases the possibilities of success. A careful statement of policy goes far toward preventing situations in which rewards are offered for results not desired by either the organization or employees. Participation in policy making helps ensure both the commitment of resources and energy required by management, as well as the favorable attitudes of employees and the union.

Administrative Support. Variable pay plans require expert staff support for proper operation, especially a heavy commitment of resources to industrial engineering. Unless the industrial engineers can carry out the standardization and measurement work as well as plan maintenance, the variable pay plan will quickly fall apart.

There is also likely to be pressure to expand variable pay coverage to other workers in order to bring their earnings up to the level of those of variable pay plan workers. Ensuring that such expansion is economically justified requires expert administrative support and upper-management decision making based upon the value of variable pay plans and not upon other organizational political considerations.

Supervision. Variable pay plans require good supervision. This requirement may mean selecting more capable supervisors. But it certainly means training supervisors to understand the workings of the variable pay plan and, equally important, showing supervisors that variable pay is an important means of obtaining the quality, cost, and output objectives that are their responsibility and therefore the basis of their rewards. Unless supervisors acquire the necessary skills and a strong interest in making the plan work, the variable pay plan will quickly deteriorate.

The role of the supervisor changes when a variable pay plan is installed. The control function is lessened since the variable pay plan builds in a control mechanism. On the other hand, the supervisor must ensure that the production process runs smoothly, with a minimum of down time, so that the employees may produce according to the plan. Supervisors spend more time in liaison and training and less in directing their workers.

Employee Perceptions. Employees must accept the variable pay plan as fair if it is to work. Obtaining this belief requires a continuing communications effort. Emphasizing the prospect of steady employment and allaying other fears is necessary to obtain employee belief in the fairness of the plan.

Employees must accept the conditions of the plan. Furthermore, the conditions should not be changed except under agreed upon circumstances. Employee fear of rate cutting is the force behind restricted output and employee distrust of variable pay plans. Accepted standards require capable administrative staff and supervisors who are not only technically competent but also able to secure employee approval of standards and the standard-setting process. Successful variable pay plans emphasize measurement rather than negotiation in the setting of standards. Obviously, acceptance of measurements requires confidence in management's fairness and good labor relations.

Keeping the variable pay plan simple and understandable to employees is essential. All procedures should be as simple as possible. Complicated earnings formulas should usually be avoided. Employee trust requires that employees understand how the plan works and exactly how it affects their pay.

Establishment of Performance Standards. As indicated, performance standards lie at the heart of any variable pay plan. How these standards are set goes a long way toward achieving their acceptance. Participation is one way to aid in acceptance. There also needs to be an established process for contesting standards. The solutions must be acceptable to both the employees and the organization.

Developing acceptable original standards is not as difficult as obtaining acceptance of changes to established standards. Because of employees' fear of rate cutting and job loss, any change in standards is likely to be resisted, no matter how justified. Changes in materials, methods, and equipment require changes in standards if the variable pay plan is not to become uneconomical for the organization. Still, any changes in standards should be a last resort and should be carefully explained to employees.

Failure to Meet or Exceed Standards. This should be carefully investigated, and the reasons found and corrected. The failure may be due to poor standardization of materials and equipment, in which case employees have the right to request a revision of the standard. If the failure is due to inadequate training or neglecting to follow the prescribed methods, these cases call not for a revision of the standard, but for better supervision and training. Paying the worker "average earnings" if he or she fails to reach standard rather than finding and correcting the reason for the failure, weakens variable pay plans.

As indicated, most variable pay plans contain a base rate that guarantees the employee a base salary regardless of their personal production rate. The relationship among base rates should be determined by job evaluation and market rates, just as with any job in the organization.

Organizational Pay Relationships. Pay relationships between jobs become more important when there is a variable pay plan in the organization. If earnings of low-skilled employees on variable pay exceeds those of high-skilled employees not on variable pay, a perception of inequity is created that will lead to pressure for increases in salaries for those not under the variable pay plan, whether or not there is any basis for these increases. Under individual and small-group variable pay plans, continually monitoring pay relationships involves an additional commitment of resources.

As we have noted, extra earnings using the plan must be sufficient to provide incentive for extra effort. With reasonable effort most workers should be able to attain some incentive earnings. The average worker on variable pay is usually expected to earn a 25-30 percent bonus. Individual workers are expected to vary around the normal bonus rate. Theoretically, of course, there is no ceiling on earnings. Establishing one would, in essence, cut rates and reduce the plan's incentive value for high producers.

Variable Pay Plan Maintenance and Audit. More variable pay plans fail because of inadequate maintenance than for any other reason. There is a constant tendency for variable pay plans to erode.25 Although changing the plan has its hazards, ignoring the constant changes that occur in the organization can lead to a situation where the standards are too loose and the variable pay plan is costing too much and not providing for extra effort.

Many organizations with successful variable pay plans audit all phases of their variable pay plan operation at regular intervals of one year or less. Standards are audited by analyzing an operation selected at random, almost as if an original standard were being developed: materials, methods, operator proficiency, and equipment are all checked and compared with the existing standard. The timekeeping and reporting systems are also audited, as are earnings relationships among individuals and groups. The latter are subjected to statistical analysis of earnings distributions.

An advantage of the periodic audit is the assurance that high earnings are not used as a signal to revise standards but that every standard is periodically audited and revised up or down as prevailing circumstances dictate. Union officials, recognizing the desirability of a consistent rate structure and the elimination of inequities, find the approach logical. Employees are less likely to resent changes wrought by an agreed-on system.

PROBLEMS OF VARIABLE PAY PLANS

Although there is a great deal of evidence that variable pay plans can improve employee performance, there is also much evidence that they have dysfunctional consequences. If this were not true, variable pay plans would undoubtedly be more popular than they are. The problems of variable pay plans fall into two categories – practicality and perception.

Problems of Practicality

With variable pay plans there are many things that it might be possible to do but are not worth doing because they cost too much, either directly or indirectly. There is evidence, for example, that variable pay plans, especially individual ones, are susceptible to restriction of output. This phenomenon results in productivity considerably below worker capability.26

The reason for restriction of output has been shown to be worker beliefs that additional productivity will lead to a rate cut or to employees working themselves out of a job. These beliefs presumably result in group pressures to restrict output.

It has also been shown that the competition created by individual variable pay plans can cause serious problems if the work calls for cooperative effort. People can be expected to exhibit behavior that is rewarded, and cooperative behavior is not rewarded or recognized under an individual variable pay plan. In fact, it has been suggested that variable pay plans cause employee resentment because they reward only effort, although employees know that many other contributions are required by the organization.

A problem implied above is the high administrative costs of a variable pay plan. Although there is no question that determining standards, measuring output, and maintaining the plan are more costly than administering a pay-for-time-worked plan, studies cited earlier concerning cost reductions under variable pay suggests that productivity increases often offset the additional costs.

Another problem of variable pay plans, noted earlier, is the tendency for internal wage and salary relationships to be distorted, such that lower-skilled variable pay based workers may earn more than high-skilled workers not under the plan. Interestingly, this problem as well as inter-group conflict, has been credited with the move toward expanding variable pay plans at the plant and organizational levels. Although the studies to date have not proved that these broader plans avoid these problems, there is evidence that they can encourage cooperation and offer suggestions (not proof) that output restriction is less likely. The numerous changes that accompany the installation of a company-wide plan make determining the source of results especially difficult. At any rate, there is no reliable evidence comparing the relative effectiveness of individual, group, and organization-wide plans.

Problems of Perception

The performance-motivation model is a perceptual model: it states that people will behave in a given way provided they perceive certain things. This section will reexamine this model to see what problems of perception variable pay plans can elicit.

The Importance of Pay. Variable pay plans rely on pay as being the most important reward for the employee. This is certainly a reasonable assumption but pay is not the only reward that is important to employees. There are many non-financial rewards that employees need and desire in their work relationship. Variable pay plans not only ignore most of these other rewards but often thwart their satisfaction. The discussion on restriction of output and its causes is a good example. The reason that variable pay plans have problems of this kind is that they prevent employees from satisfying their social needs. Where desires for different rewards come into conflict, the motivational strength of the plan is diminished.

The Performance-Reward Connection. As we have seen, the most important aspect of variable pay plan design is the determination of the performance standards and the ratio of rewards to those standards. This is easy to say and hard to do. Performance is difficult to define for all jobs. It is even harder to define all the performance variables and relate them to the rewards. What occurs is a dilemma. To include all the variables and make the connections, the plan becomes complex. This in turn violates the simplicity principle and increases the probability that the employee will not understand the plan.

Establishing performance standards is a continual problem. To the degree that it is done by management for the employee, its acceptance by the employee depends upon the faith that the employee has in management. The constant fear of the employee, as we have noted, is of rate cutting. Thus, any change in the standards whether justified or not, will be viewed with suspicion. Again, variable pay plans require trust between management and labor, something that is not common in our society. Even where there is trust, the process of setting standards is judgmental, suggesting that there is always the possibility of inequity. It is therefore wise to have a formal appeal system, whether there is a union or not. Further, employees see the definition of performance by management, in some cases, as breaking down the skill requirements of the job and thereby making the job less intrinsically appealing.

Although the connection between performance and reward is clear in the short run, it may not be so in the long term. As we have seen, the employee may perceive that to produce above the standard is to work oneself out of a job. This becomes a further reason to restrict output and to encourage others to do likewise. A further concern of employees may be that the proportion of the gain made under the variable pay plan goes mostly to the organization and not to the employees.

The Performance-Effort Connection. The final part of the performance-motivation model is the connection between performance and effort. The purpose of variable pay plans is to increase the effort of employees and thereby their output. Obviously, this assumes that the employee's effort makes a difference in the output, but this is not always true, at least not at a level that allows the performance-effort connection to operate.

Employees have concerns about attempts to increase effort. They may feel that management is trying to get more than a fair day's work for a fair day's pay. Or they may feel that variable pay plans are excuses for a speedup by management. At the extreme, the pressure for more effort may lead to stress and fatigue.

In order to have high earnings, the employee under a variable pay plan must put out a consistently high level of effort. This may not be a natural pace for people. Most of us are able to work faster at certain times of the day than at others, so a constant high level of effort is almost impossible to maintain. Employees who cannot keep up are going to feel a great deal of frustration and concern for their continued employment.

Furthermore, base rates in variable pay plans that are established through industrial engineering assume that all people have the same ability to achieve the standard or higher. This is not true. Thus, there are some employees for whom the performance-effort connection is low because they are easily able to meet the standard, and others for whom the connection is low because they must put forth too much effort to meet it. Yet it is impossible to have different standards, since that would be perceived as unfair.

All of these perceptual concerns that employees may have, make it more difficult for the performance-motivation model to operate and therefore reduce the effectiveness of a variable pay plan. Management and the compensation staff need to recognize the possible presence of these concerns and deal openly with them through open communication with the employees.

SUMMARY

The use of variable pay plans for an ever widening range of jobs, many of which were considered inappropriate jobs for variable pay plans in the past, has been on the rise. The reason for this has been the need to focus on productivity and the known positive results of variable pay plans. The use of variable pay plans comes the closest to using the performance-motivation model in the design of a compensation plan.

There are three essential elements to variable pay plans. First, the unit of the variable pay plan, called the level of aggregation, is determined. Variable pay plans are ordinarily categorized into individual, group, or organization-wide (organizational). Each of these levels designates the point at which output, or productivity, is defined as well as categorizing the group that receives the rewards. Second, and most important, a performance standard is set. In individual and group plans the standard is usually some statement of output or time, or both elements together. In organizational plans, standards of performance are based on reductions in cost, improvements in overall productivity, increased profits, or a combination of all three factors. Third, is the reward(s) offered. The rewards are usually money, but time can also be a potent reward. Money needs to be in significant quantity and received in a timely fashion, so the connection is clear.

Designing variable pay plans requires making a further set of decisions. The first of these is coordination of the variable pay plan with the organization's strategy, including organizational conditions such as the size of the organization, labor costs, and managerial attitudes. The second set of decisions has to do with the jobs to be included. This is important because some jobs are not amenable to variable pay plans. Determining the applicability of variable pay is a third decision. In general, in the past, applicability has been too narrowly defined. Another decision has to do with the manner in which performance and reward are connected. This requires a clear definition of performance, a ratio between performance and reward, and determination of the proportion of total pay controlled by the variable pay plan. Finally, variable pay plans require well-devised administration and constant surveillance for optimum operation.

Variable pay plans are not always popular because they have problems that may make them not worth their advantages. The assumption that workers operate only on an economic level is not supported when one sees the restriction of output that often occurs in variable pay plans. Variable pay plans also require considerable administrative costs, take control away from supervisors, and require a supportive climate within management. Further, the inability to define performance in a way that is complete and acceptable often has doomed variable pay plans. Changing the conditions of the plan once established is very difficult, as it is often seen as taking away things from the employee. Finally, variable pay plans for one group in the organization may be perceived as inequitable by other groups in the organization.

Footnotes

1 International Labour Office, Payment by Results (Geneva, 1984). This publication is a major source in the development of this chapter. It is recommended for anyone interested in incentive pay plans.

2 Bloom, M. & Milkovich, G. "The Relationship Between Risk, Incentive Pay and Organizational Performance" Academy of Management Journal, Vol 14 #3, 1998, pp.283-297.

3 Lawler, E., Mohrman, S. & Ledford, G., Creating High Performance Organizations: Practices and Results of Employee Involvement and TQM in Fortune 1000 Companies, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1995.

4 H. K. von Kass, Making Wage Incentives Work (New York; American Management Assn., 1971), p. 11.

5 "Variable Pay Plans Fall Short of Expectations," ACA News, Vol.41 #7 July/August 1998.

6 Kohn, A. Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Systems, A's Praise and Other Bribes, Boston, Houghton-Mifflin, 1993.

7 Heneman, R. Merit Pay: Linking Pay Increases to Performance Ratings, Reading, MA., Addison Wesley Longman, 1992

8 Ducharme, M. & Podolsky, M. "Variable Pay: Its Impact on Motivation and Organizational Performance" International journal of Human Resource Development and Management, Geneva, Vol. 6, #1, 2006.

9 Heneman, R. & Gresham, M. "Performance-Based Pay Plans" in Heneman, R. Strategic Reward Management: Design, Implementation and Evaluation, Greenwich, Conn. Information Age Publishing, 2002.

10 E. A. Locke, D. B. Feran, V. M. McCaleb, K. N. Shaw, and A. T. Denny, "The Relative Effectiveness of Four Methods of Motivating Employee Performance," in Changes in Working Life, ed. K. D. Duncan, M, M. Greenberg, and D. Wallace, (New York: John Wiley, 1980), pp. 363-388.

11 International labour Office, OP Cit.

12 See F. G. Lesicur, The Scanlon Plan: A Frontier in Labor--Management Cooperation (New York: John Wiley, 1958).