Chapter 11: Job Evaluation

Overview: This chapter describes how to conduct job analysis and job evaluation to establish a rational salary structure.

Corresponding course:

34 Using Job Evaluation in Your Organization

INTRODUCTION

Two often-cited principles of compensation:

- equal pay for equal work and

- more pay for more important work

Both imply that organizations pay employees for what they do – their jobs. Figuring out whether jobs are equal or unequal and by how much, requires the development of a hierarchy of jobs by the organization. This process is job evaluation.

Most organizations utilize the job as a major determinant of pay. Some sort of salary structure, defined as a pay rate or pay range established for groups of jobs, is common in almost all organizations, except very small ones. Formal job evaluation or informal comparison of job content has an almost universal influence upon pay rates.

Job evaluation is the process of methodically establishing a hierarchy of jobs within an organization. This is based on a systematic consideration of job content and requirements. The purpose of the job structure, or hierarchy, is to provide a basis for the development of a salary structure. The job structure, however, is only one of the determinants of the salary structure, with other factors becoming increasingly more important. These are the topics for Chapter 12.

Job evaluation is concerned with jobs, not people. A job is a grouping of work tasks. It is a concept requiring careful definition in the organization. Job evaluation determines the relative position of the job in the organization hierarchy. It is assumed that as long as job content remains unchanged, it may be performed by individuals of varying ability and proficiency.

This view of job evaluation implies that its major purpose is to classify jobs and establish a job hierarchy based on job content. Other perspectives are the job evaluation (1) links external and internal markets, and (2) is a process used to gain consensus and acceptance of a pay structure.1 Perhaps these views could all be accommodated by the recognition that job structures and salary structures are separate concepts and that the relationship between them is a decision that varies among organizations.

Objectives of Job Evaluation

The general purpose of job evaluation, that of establishing a job hierarchy, may include a number of more specific goals, including to provide a/an:

- basis for a simpler, more rational salary structure

- agreed-upon means of classifying new or changed jobs

- means of comparing jobs and pay rates with those of other organizations

- base for individual performance measurements

- way to reduce pay grievances by reducing their scope and providing an agreed-upon means of resolving disputes

- incentive for employees to strive for higher-level jobs

- source of information for wage negotiations

- data source on job relationships for use in internal and external selection, personnel planning, career management, and other personnel functions

Background of Job Evaluation

Job evaluation developed out of civil service classification practices and some early employer job and pay classification systems. Whether formal job evaluation began with the United States Civil Service Commission in 18712 or with Frederick W. Taylor in 1881,3 it is now over 120 years old and still of great value. The first point system was developed in the 1920s. Employer associations have contributed greatly to the adoption of certain plans. The spread of unionism has influenced the installation of job evaluation in that employers gave more attention to rationalized salary structures as unionism advanced. During World War II, the National War Labor Board encouraged the expansion of job evaluation as a method of reducing pay inequities.

As organizations became larger and larger and more bureaucratized the need for a rational system of paying employees became evident. Salary structures became more complex and needed some way to bring order to the chaos perpetuated by supervisors setting pay rates for their employees on their own. Job evaluation became a major part of the answer. The techniques and processes of job evaluation were developed and perfected during this time period of the late 1950s.

With the advent of the Civil Rights movement, job evaluation literally got written into the law. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 required jobs to be compared on the basis of skill, effort, and responsibility to determine if they were or were not equal. A 1979 study of job evaluation, as a potential source of and/or a potential solution to sex discrimination in pay, was made by the National Research Council under a contract from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.4 The study suggested that jobs held predominantly by women and minorities could be undervalued. Such discrimination resulted from the use of different plans for different employee groups, from the compensable factors employed, from the weights assigned to factors, and from the stereotypes associated with jobs. Although the preliminary report failed to take a position on job evaluation, the final report concluded that job evaluation holds some potential for solving problems of discrimination.5

Prevalence of Job Evaluation

Job evaluation is used throughout the world. Although recent evidence is not available, it appears that job evaluation is still more prevalent in the United States than elsewhere. However, a 1982 International Labor Office publication states that in centrally controlled economies or in economies where pay or income controls exist, job evaluation is frequently used.6 Furthermore, England and Canada are showing increases in the use of job evaluation at a time when there are declines in its usage in the U.S.7

Holland has had a national job evaluation plan since 1948 as a basis for its national wages and incomes policy. Sweden and Germany have a number of industry-wide plans. Great Britain, like the United States, usually employs job evaluation at the plant or company level. Australia and some Asian countries have installed some forms of job evaluation. Russia and some of the other Eastern European countries make wide use of job classification.

The evidence on use of job evaluation in the United States shows that smaller companies are somewhat less likely to use job evaluation.8 Almost all government jurisdictions, however, employ some form of job evaluation.

Starting in the early 1970's job evaluation has come under attack in the United States. This has come about from a change in the American economy and the type of organizations that dominate the new economy of today. Job evaluation works best in large bureaucratic organizations and these behemoths of the American economy have faced increasing problems remaining competitive. The result is that they have downsized greatly and removed many layers of organization. Vertical movement within organizations has slowed down and employees increasingly move to jobs in other organizations rather than stay with their current employer. The new companies gaining a foothold in the economy are smaller and organizationally flexible. There are also fewer unions; individuals now bargain for their own pay. Lastly, organizations are putting more emphasis on employee skills and performance, as opposed to the job.9

All this does not mean that organizations ignore the job as a determinant of pay. What has happened is that pay systems have become more flexible and they weight both skill and performance more heavily. The use of salary survey data for more and more jobs is increasing; it is made more practical as data has become readily available on the Internet. Within organizations, job evaluation systems have become simpler, less formal and have less complexity.

One example of this has been broadbanding. In broadbanding, the number of levels in the job evaluation plan is reduced, while the width of the grade levels is increased dramatically. This allows employees to receive pay increases without having to move up to a new grade level that is tied to a higher organizational level.10

THE JOB EVALUATION PROCESS

Job analysis describes a job. Job evaluation develops a plan for comparing jobs in terms of those things the organization considers important determinants of job worth. This process involves a number of steps that will be briefly stated here and then discussed more fully.

- Job Analysis. The first step is a study of the jobs in the organization. Through job analysis, information on job content is obtained, together with an appreciation of worker requirements for successful performance of the job. This information is recorded in the precise, consistent language of a job description. This was the topic of chapter 10.

- Compensable Factors. The next step is deciding what the organization "is paying for" -- that is, what factor or factors place one job at a higher level in the job hierarchy than another. These compensable factors are the yardsticks used to determine the relative position of jobs. In a sense, choosing compensable factors is the heart of job evaluation. Not only do these factors place jobs in the organization's job hierarchy, but they also serve to inform job incumbents which contributions are rewarded.

- Developing the Method. The third step in job evaluation is to select a method of appraising the organization's jobs according to the factor(s) chosen. The method should permit consistent placement of the organization's jobs containing more of the factors higher in the job hierarchy, than those jobs lower in the hierarchy.

- Job Structure. The fourth step is comparing jobs to develop a job structure. This involves choosing and assigning decision makers, reaching and recording decisions, and setting up the job hierarchy.

- Salary Structure. The final step is pricing the job structure to arrive at a salary structure. Strictly speaking, this step is not part of job evaluation and is covered in chapter 12.

COMPENSABLE FACTORS

After the job information has been collected through job analysis, the organization needs to determine what it wishes to "pay for" – decide what is of value to them. What aspects of a job place it higher in the job hierarchy than another job. These yardsticks are called compensable factors.

In the previous chapter we suggested that the job information needed for job evaluation consists of work activities and worker requirements. But what aspect or aspects of work activities and/or which worker requirements are to be used? The choice of yardstick will strongly influence where a job is placed in the hierarchy. Some job analysis requires the analyst to describe jobs in terms of pre-selected factors. This practice seems to assign to job analysts not only the analysis but the evaluation of jobs. The Position Analysis Questionnaire is one such job analysis technique.

Choosing Compensable Factors.

To be useful in comparing jobs, compensable factors should possess certain characteristics.

- First, they must be present in all jobs.

- They need to be definable and measurable.

- The factor must vary in degree. A factor found in equal amounts in all jobs would be worthless as a basis of comparison.

- If two or more factors are chosen, they should not overlap in meaning. If they do overlap, double weight may be given to one factor.

- Employer, employee, and union viewpoints should be reflected in the factors chosen; consideration of all viewpoints is critical for acceptance.

- Compensable factors must be demonstrably derived from the work performed. The factors must be observable in the jobs. For this reason responsibility is a hard factor to use. Compensable factors can be thought of as the job-related contributions of employees. Documentation of the work-relatedness of factors comes from job descriptions. Such documentation provides evidence against allegations of illegal pay discrimination. It also provides answers to employees, managers, and union leaders who raise questions about differences among jobs.

- Compensable factors need to fit the organization. Organizations design jobs to meet their goals and to fit their technology, culture, and values.

Job evaluation plans vary in the number of factors they employ. Nine to eleven factors are not unusual, and single-factor plans exist, but three to five is most typical. Jaques' Time Span of Discretion (the time before sub-marginal performance becomes evident) may be considered a single-factor plan, although Jaques insists that it represents measurement.11 Other such single-factor plans are Charles's plan, which is based on problem solving12 and Patterson's decision-band method.13

Methods of Determining Compensable Factors. There are three major ways in which organizations can determine what compensable factors to use. First, many organizations adopt standard job evaluation plans and thus the factors on which they are based are predetermined. Most organizations that do this, adjust existing plans to their own requirements. The factors in most existing plans tend to fall into four broad categories: skills required, effort, responsibilities, and working conditions. These factors are used in numerous job evaluation plans. They are also the factors written into the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and used to define equal work.14

Definitions and divisions of these factors vary greatly. The years of education required by the job are a common definition of skill, as is the experience required. Skill is likewise often divided into mental and manual skills. In this way, a job evaluation plan may be tailored to the needs of the organization.

Secondly, organizations may develop their own set of factors through a group process method. This method requires bringing together a group of experienced people who know a great deal about the jobs to be evaluated. These people are asked to review the job descriptions of a select group of key jobs and to list all the job characteristics, requirements, and conditions that, in their opinion, should be considered in evaluating the jobs. The group then must come up with job attributes, which then get placed into a limited number of categories.

Another type of group would be a union-management joint committee. This committee would follow the same process as discussed above, but often the decision making has more political overtones than a committee appointed by management. Employee acceptance of factors tends to be enhanced by their involvement in determining them.

Thirdly, compensable factors can be derived statistically from quantitative job analysis. For example, the factors in the Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ) used for job evaluation were obtained by finding those elements most closely related to pay.15 Statistical techniques may help ensure that the factors chosen are related to the work and are legally defensible. But factors derived statistically are not always accepted by employees as applicable to their jobs. Developing a statistically based job evaluation plan consists of the following steps:

- Develop and administer a structured questionnaire that can be computerized on a sample of key jobs.

- Develop and gather data for a dependent variable.

- Develop and test a multiple regression model on the benchmark jobs.

- Make any required revisions and gather data from remaining jobs and apply model to the entire organization.16

The major advantage of the statistical approach is that it can determine how reliably the factors measure the jobs. Unfortunately, the funds and the expertise needed to conduct statistical analysis are not always available. The committee and the questionnaire approaches may yield equally useful compensable factors if based on adequate job descriptions.

Compensable Factors and Organizational Strategy. The importance of carefully choosing compensable factors cannot be exaggerated. The symbolism is clear-"This is what we pay for around here!" There is a great deal of discussion in both Human Resource and Compensation literature about the need to have Human Resource practices consistent with corporate strategy; human resources needs to be more in tune with the business. Here is the ideal place for this. Developing factors that are consistent with the employees' concerns about the strategy of the organization, may be one of the best opportunities for compensation practices to contribute to organizational strategy.17

Number of Plans

Whether to employ a single plan to evaluate all the organization's jobs or a separate plan for each of several job families must also be decided.

Arguments for Multiple Plans. There is a strong tendency for organizations, especially large ones, to use multiple plans. Using different compensable factors for different job families may be justified in several ways. The organization may be paying for different things in different job groups. Also, the salaries of different job families do not always move together and in equal amounts.

Equally important, Livernash has shown that job-content comparisons are strongest within narrow job clusters and weakest among broad job clusters.18 Employees in the same job family are likely to make job comparisons. Job relationships are likely to be influenced by custom and tradition, as well as by promotion and transfer sequences.

For all these reasons, organizations commonly have separate job evaluation plans for different functional groups (for example: production jobs, clerical jobs, professional and technical jobs, and management jobs).

Although a number of organizations are opting for a single plan, defining compensable factors that are applicable to all jobs and acceptable to employees is difficult. As a consequence, there may be a growing tendency for organizations to use fewer plans. An advantage would be that these plans can be keyed to job groups whose incumbents are balanced by gender and race. One alternative would be (1) make a plan for service or production and maintenance jobs, paid primarily for physical skills, (2) make a plan for office and technical jobs, paid primarily for mental skills, and (3) make a plan for exempt jobs (managerial and professional), paid primarily for discretionary skills.

Another possible approach is a common set of compensable factors used along with a set of factors unique to particular functional areas. The latter tend to make the plan more acceptable to employees and managers. Where more than one job evaluation plan is used and questions of bias are raised, it is common to evaluate the job in question with other plans and compare results. Organizations that employ more than one job evaluation plan should identify a series of jobs that can be evaluated on two plans to ensure consistency of results across plans.

While a single plan can work, it is still more common for organizations to have more than one job evaluation plan. The plan may have quite different factors or merely different definitions for the same factors. In the former case, factors such as responsibility and decision making are used for executive jobs, while physical demands and skills are categorized for manual jobs, and the accuracy and amount of supervision is specificed for clerical and technical jobs. The rationale for different plans for different job families is that the organizations pay for different things in different job families.

Arguments for a Single Plan. Equal employment opportunity rules may be encouraging organizations to reexamine their choice of multiple plans rather than a single plan. Obviously, comparing all jobs within an organization for evidence of discrimination, based on sex or race, suggests employing a single plan. The National Academy of Sciences study for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission argued strongly in its interim report (but not the final report) for a single plan for the organization.19

A number of plans are designed to evaluate all the jobs in an organization. Elizur's Scaling Method of Job Evaluation is one such method.20 It reportedly has the additional advantage of meeting the requirements of a Guttman scale. The Factor Evaluation System (FES) developed for federal pay grades 1-15 can also be considered a total organizational plan.21 Such plans can be expected to become increasingly popular, in view of the need to comply with the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs [OFCCP] requirements to make job comparisons in order to eliminate pay discrimination.22

An increasingly popular job evaluation technique is to use a standardized job analysis questionnaire. For example, the Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ)23 discussed in the previous chapter, has been used in numerous organizations for establishing policies capturing the job dimensions by regressing them against pay rates for jobs. Although only nine of the PAQ elements are typically used for job evaluation, they are very similar to those found in traditional plans. The expanding use of software technology solutions has undoubtedly made these types of job evaluation plans more practical.

Some job evaluation plans actually rely almost entirely on labor-market information. The guideline method of job evaluation, for example, collects market-pay information on a large proportion of the organization's jobs and compares the "market rate" with a schedule of pay grades constructed on 5 percent intervals. The schedules include midpoints and ranges of 30 to 60 percent. Job evaluation consists of matching market rates to the closest midpoint. Adjustments of one or two grades may be made to accommodate internal relationships. Key jobs are placed into grades and the remaining jobs positioned by comparison with them.24

TYPES OF JOB EVALUATION PLANS

The next step in the job evaluation process is to select or design a method of evaluating jobs. This section will start by taking a closer look at the concept of market pricing that was introduced in Chapter 9. Then we will examine the four most common ways to develop job hierarchies using job evaluation.

Market Pricing

Market pricing is both more and less than job evaluation. It is more than job evaluation in that the final product is a salary structure, not a job structure as in job evaluation. It is less than job evaluation in that it provides a salary structure based solely upon competitive wage rates. The organization's strategy is limited to the determination of the appropriate pay level and not the determination of the importance of jobs to the organization.

The main advantage of Market Pricing is its simplicity, as compared to job evaluation both technically and in terms of understandability, to managers and employees. Further, while job evaluation needs to be translated into a salary structure, market pricing leads directly to a salary structure. In recent years the importance of the market, vis-à-vis the internal considerations of jobs has increased, making market pricing more on the cutting edge of compensation practices. This has been aided by an increase in the amount and quality of salary data.

The major disadvantage to market pricing has already been mentioned- the narrow focus on only the organization’s competitive labor market position. Perhaps more of a disadvantage overall, however, is the fact that many jobs within an organization do not have a direct market equivalent and must somehow be placed into the resulting structure. This is done by slotting these jobs in where they appear appropriate. This, of course, is a crude form of job evaluation requiring the analyst to compare jobs and put them into the structure where they seem to fit. Lastly, market pricing increases the business risk of discrimination to minorities and women.25

A discussion of the steps needed for developing a market pricing system is located in the appendix to this chapter.

Job Evaluation Methods

Four basic methods have traditionally been said to describe most of the numerous job evaluation systems: ranking, classification, factor comparison, and the point plan. The dimensions that distinguish these methods are (1) qualitative versus quantitative, (2) job-to-job versus job-to-standard comparison, and (3) consideration of the total job versus separate factors that when summed, make up the whole job. These four methods as listed here may be thought of as increasing in specificity of comparison. Ranking involves creating a hierarchy of jobs by comparing jobs on a global factor that presumably combines all parts of the job. The classification method defines categories of jobs, referred to as classifications, and slots jobs into these classes. Factor comparison involves job-to job comparisons on several specific compensable factors. The point method compares jobs on rating scales of specific factors.26 These classifications of job evaluation methods are illustrated in figure 11-1.

These four basic methods are pure types. In practice there are numerous combinations. Also, there are (as mentioned) many ready-made plans as well as numerous adaptations of these plans to specific organization needs. This section provides a basic description of each of these four methods. A more extensive explanation of each method is provided in the appendix to this chapter.

As will be seen, some job evaluation methods are classified as whole-job methods, implying that compensable factors are not used because "whole jobs" are being compared. If this means that one broad-based factor rather than several narrower factors is employed, no problem occurs. But if whole-job means that jobs can be compared without specifying the basis of comparison, the result may be a different basis of comparison for each evaluator. If this reasoning is correct, then useful job evaluation must always utilize one or more compensable factors.

| QUALITATIVE | vs. | QUANTITATIVE |

| Ranking | Factor Comparison | |

| Classification | Point Plan |

| JOB-TO-JOB | vs. | JOB-TO-STANDARD |

| Ranking | Point Plan | |

| Factor Comparison | Classification |

| TOTAL JOB | vs. | SEPARATE FACTOR COMPARISONS |

| Ranking | Factor Comparison | |

| Classification | Point Plan |

Job Ranking.

As its name implies, this method ranks the jobs in an organization from highest to lowest. It is the simplest of the job evaluation methods and the easiest to explain. Another advantage is that it usually takes less time and so is less expensive.

Its primary disadvantage is that its use of adjacent ranks suggests that there are equal differences between jobs, which is very unlikely. Other disadvantages stem from the way the method is often used. For example, ranking can be done without first securing good job descriptions. This approach can succeed only if evaluators know multiple aspects of all the jobs, which is virtually impossible in an organization with many jobs or with frequently changing jobs.

Another disadvantage is that rankers are asked to keep the "whole job" in mind and merely rank the jobs. This undoubtedly results in different bases of comparison among raters. It also permits raters, whether they realize it or not, to be influenced by such factors as present pay rates, competence of job incumbents, and prestige of the job. This difficulty can be overcome by selecting and defining one or more compensable factors and asking raters to use them as bases of job comparison. Even then, unfortunately, factor definitions are often so general that rankings are highly subjective.

If the ranking method is used in accordance with the processes described in the appendix to this chapter, it may yield the advantages cited and minimize the disadvantages. Although job ranking is usually assumed to be applicable primarily to small organizations, it has been used in large firms as well. Computers make it possible to use paired comparisons for any number of raters, jobs, and even factors. All this said, the other disadvantages remain. Unless job ranking is based on good job descriptions and at least one carefully defined factor, it is difficult to explain and justify in work-related terms. Although the job hierarchy developed by ranking may be better than paying no attention at all to job relationships, the method's simplicity and low cost may produce results that are disputed by employees and managers.

Job Classification

The classification method involves defining a number of job categories and fitting jobs into them. It would be like sorting books among a series of carefully labeled shelves in a bookcase. The primary task is to describe each of the classifications so that fitting each job into its proper niche category can be done easily and objectively. The assigned job classifications are then validated by comparing each job with the classification descriptions provided.

Advantages. The major advantage of this method is that most organizations and employees tend to classify jobs. It may therefore be relatively easy to secure agreement about the classification of most jobs. The classification method also promotes thinking about job classes among both managers and employees. If jobs are thought of as belonging in a certain grade, many problems of Compensation Administration become easier to solve. In fact, most organizations classify jobs into grades to ease the task of building and operating pay structures. When jobs are placed into grades or classes subsequent to job evaluation by any method (or even by informal decision) those grades often become the major focus of Compensation Administration. When jobs change or new jobs emerge, they may be placed in the job structure by decision or negotiation. It may be necessary to use formal job evaluation only infrequently, when agreement cannot be reached without it.

Perhaps the greatest advantage of the method is its flexibility. Although classification is usually said to be most useful for organizations with relatively few jobs, it has been used successfully by the largest organization in the world: the United States government. In fact, it is the primary job evaluation method of most levels of government in the United States, as well as of many large private organizations. In these organizations, millions of kinds and levels of jobs have been classified successfully.

Advocates of classification hold that job evaluation by any method involves much judgment. They also believe that classification can be applied flexibly to all kinds and levels of jobs, while being sufficiently precise to achieve management and employee acceptance, as well as organization purposes. Although the federal government adopted the Factor Evaluation System (a point-factor method, discussed later) in 1975 as an easier way of assigning jobs to GS grades 1-15, many local governments continue to use the classification method.

Disadvantages. Disadvantages of classification include (1) the difficulty of writing grade level descriptions and (2) the judgment required in applying them. Because the classification method considers the job as a whole, compensable factors, although used in class descriptions, are un-weighted and un-scored. This means that the factors have equal weight, and a little of one may be balanced by much of another. Terms that express the degree of compensable factors in jobs are relied upon to distinguish one grade from another. It is quite possible that a given grade could include some jobs requiring high skill and other jobs requiring little skill but carrying heavy responsibility.

It is even possible under a classification system for a job to fit into one grade on one factor but a different grade on another. In fact, classification systems employ both the use of higher levels of a factor and additional factors in descriptions of higher grades. However, organizations may have trouble justifying and gaining acceptance of such results.

Factor Comparison Method

This method compares jobs on several factors to obtain a numerical value for each job and to arrive at a job structure. Thus, it may be classified as a quantitative method.

Factor comparison itself is not widely used: it probably represents less than 10 percent of job evaluation plans used by organizations. The concepts on which it is based are incorporated in numerous job evaluation plans, including the one that is probably used the most, the Korn Ferry Hay Plan. The factors in this plan are know-how, problem solving, and accountability.

Factor comparison involves judging which jobs contain more of certain compensable factors. Jobs are compared with each other (as in the ranking method), but on one factor at a time. The judgments permit construction of a comparison scale of key jobs against which other jobs may be compared. The compensable factors used are usually (1) mental requirements, (2) physical requirements, (3) skill requirements, (4) responsibility, and (5) working conditions. These are considered to be universal factors found in all jobs. This means that one job-comparison scale for all jobs in the organization may be constructed, and this practice is often followed upon installation of factor comparison. However, separate job-comparison scales can be developed for different functional groups, and other factors can be employed.

Factor-comparison concepts employed in other job evaluation plans should be noted. Job-ranking plans that use two or more compensable factors and weighting them differently are essentially factor-comparison plans. The practice of assigning factor weights statistically, on the basis of market rates and the ranking of jobs on the factors, employs a factor-comparison concept. The use of universal factors in the Korn Ferry Hay plan and a step called profiling are factor-comparison ideas. Finally, the use of job titles as examples of factor levels in other job evaluation plans is a factor-comparison concept.

Advantages. A major advantage of factor comparison is that it requires a custom-built installation in each organization. Such a plan may result in a better fit with the organization. Another advantage, according to its developers, is that comparable results accrue whether the plan is installed by management, employee representatives, or a consultant.27 The type of job comparisons utilized by the method is another advantage. Since relative job values are the results sought, comparing jobs with other jobs seems logical. Limiting the number of factors may be another advantage in that this tends to reduce the possibility of overlap and the consequent overweighting of factors.

Still another advantage would seem to be the job-comparison scale. Once employees, union representatives, and managers have been trained in the use of the scale, visual as well as numerical job comparisons are easily made. The use of a monetary unit in the basic method has the advantage of resulting in a salary structure as well as a job structure, thus eliminating the pricing step required in other plans. It is questionable, however, whether this advantage offsets the disadvantage of possible bias introduced by monetary units.

Disadvantages. One disadvantage of the method is its use of "universal" factors. Although, as mentioned it is quite possible for an organization to develop its own compensable factors, factor comparison uses factors with common definitions for all jobs. This means using the same factors for all job families.

The definition of key jobs may be another disadvantage. A major criterion of a key job in factor comparison is the essential correctness of its pay rate. Since key jobs form the basis of the job-comparison scale, the usefulness of the scale depends on the anchor points represented by these jobs. But jobs change, sometimes imperceptibly. When jobs change and when wage rates change over time, the scale must be rebuilt accordingly. Otherwise users are basing their decisions on what might be described as a warped ruler.

The use of monetary units may represent a disadvantage if, as is likely, raters are influenced by whether a job is high-paid or low-paid. An unnecessary possibility of bias would seem to be present when raters use the absolute value of jobs to determine their relative position in the hierarchy.

Finally, the complexity of factor comparison may be a serious disadvantage. Its many complicated steps make it difficult to explain and thus affect its acceptance.

Point Factor Method

The point-factor method, or point plan, involves rating each job on several compensable factors and adding the scores on each factor to obtain a point total for a job. A carefully worded rating scale is constructed for each compensable factor. This rating scale includes a definition of the factor, several divisions called degrees (also carefully defined), and a point score for each degree. The rating scales may be thought of as a set of rulers used to measure jobs.

Designing a point plan is complex, but once designed the plan is relatively simple to understand and use. Numerous ready-made plans developed by consultants and associations exist. Existing plans are often modified to fit the organization.

Advantages. Probably the major advantage of the point method is the stability of the rating scales. Once the scales are developed, they may be used for a considerable period. Only major changes in the organization demand a change in scales. Job changes do not require changing scales. Also, point plans increase in accuracy and consistency with use. Because point plans are based on compensable factors adjudged to apply to the organization, acceptance of the results is likely. Factors chosen can be those that the parties deem important.

Point plans facilitate the development of job classes or grades. They also facilitate job pricing and the development of pay structures.

Carefully developed point plans facilitate job rating. Factor and degree definitions can greatly simplify the task of raters.

Disadvantages. As mentioned, developing a point plan is complex. There are no universal factors, so these must be developed. Then degree statements must be devised for each of the factors chosen. All this takes time and money. Further, point plans take time to install. Each job must be rated on the scale for each factor, usually by several raters, and the results must be summarized and agreed to. Considerable clerical work is involved in recording and collating all these ratings. Much of this time and cost, however, can be reduced by using a ready-made plan.

ADMINISTRATION OF JOB EVALUATION

Both the installation and operation of a job evaluation requires work from many parts of the organization. Some of the issues are presented here.

Responsibility for Job Evaluation

The implementation and management of job evaluation involves certain responsibilities. Several possibilities for introducing the process are apparent. One or more committees may be selected, a department may be set up or an existing one assigned, or a consulting organization may be contracted. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive.

Support for the program is essential because implementing it involves commitments of time, effort, and money. Such support is usually obtained by securing top management approval and the collaboration of other managers and organization members. Often this approval is obtained through a committee set up for this purpose.

The Committee Approach. This committee is given an explanation of job evaluation, the purposes it is expected to accomplish, a rough time schedule, and perhaps an estimate of the program cost. The committee makes the decision to install job evaluation, decides on the scope of the project, and assigns responsibility for the work.

The actual job evaluation work is usually done by the committee in both large and small organizations, whether the task is accomplished by organization members alone or with the help of a consultant. Committees have the advantage of being able to pool the judgment of several individuals. The committee usually selects the compensable factors, determines weighting, chooses the method of comparing jobs, and evaluates jobs.

The chair of the committee is usually an organizational compensation professional, although a consultant, if employed, may assume the chair for part of the work. Other members are typically other managers selected for their analytical ability, fairness, and commitment to the project. Representation of broad areas of the organization aids in communication and in gaining acceptance. Job evaluation committees should be kept small to facilitate decision making. Five members may be optimum, ten a maximum. A common procedure is to invite supervisors to committee meetings when jobs in their department are under study.

In union-management environments, union members are regular members of the committee. Where the union is not involved, employee representation is often rotated. Employee representation in committees seems to aid in securing acceptance and in communication.

Committee job ratings are a result of pooled judgments. This usually means either that ratings made individually are averaged or a consensus is reached as a result of discussion.

Committee members must be trained. Much of this training involves following the steps in the process. But it is advisable to train committee members how to guard against personal bias and the common rating errors.

Consultants. Consultants are often employed to introduce job evaluation plans. Successful consultants are careful to ensure that organization members are deeply involved in the process and are able to manage the plan on their own.

Consultants are most likely to be employed in organizations where no member has the necessary expertise. They are also more likely to be employed when a complex, rather than a simple plan, is to be introduced. Consultants often have their own ready-made plans. Sometimes consultants are brought in to insure objectivity in union-management installations. It is also common to hire consultants to evaluate management jobs, because the objectivity of committee members rating jobs at levels higher than their own may be questioned.

Compensation Department Involvement. It is quite possible for the organization to assign the job evaluation plan project to the Human Resources department. Sometimes a compensation professional and a number of job analysts carry out the task. Those who favor this last approach emphasize the technical nature of the task. They may also be reacting to the difficulty of getting operating managers to devote the time that the program requires. While they may recognize the education and communication advantages of committees, they believe these advantages can be provided in other ways. Input by operating managers and perhaps employees during job evaluation implementation are essential to acceptance of the results. Once the program is implemented, however, Human Resources can manage it with proper provisions for settling grievances.

Union Involvement in Job Evaluation. Union involvement in job evaluation committees leads to acceptance and an understanding of project outcomes.

In practice, union participation in job evaluation has varied greatly. Some unions profess to formally evaluate an organization's jobs independently and then use the information as an aid in collective bargaining. Some job evaluation plans have been introduced and maintained as a joint venture. A well-known union-management job evaluation plan exists in the steel industry. Less well-known is the joint plan in the West Coast paper industry. There is evidence that joint plans are more successful than unilateral plans. But this is not always the case.

Many unions in organizations review the findings of job evaluation plans after they have been implemented by management and either present grievances on individual jobs or insist on bargaining the wage structure. In the latter case, the bargained wage structure may follow the job structure resulting from job evaluation, or be a negotiated compromise.

Some unions have ignored job evaluation plans unilaterally implemented by management. Some employers prefer this response, believing that job design and evaluation are management prerogatives. Other employers invite union participation in the hopes of obtaining understanding and acceptance of the plan.

If a union rejects an invitation to participate in job evaluation and ignores the plan, the employer installs the plan unilaterally, recognizing the need for a logical hierarchy of jobs. The findings are used in negotiating the wage structure.

Unions have criticized job evaluation on several grounds:

- that it restricts collective bargaining on wages,

- that wages shouldn't be based solely on job content,

- that supervisors do not or cannot explain the plan to employees,

- that management doesn't administer the plan the way it was explained, and

- that it is subjective.

Employee Acceptance

In this chapter we have frequently mentioned the importance of acceptance of job evaluation results by employees and managers. In fact, job evaluation is usually judged successful when employees, unions, and organizations report satisfaction with it. Most surveys report organization satisfaction levels at 90 percent or better. Employee acceptance is the primary criterion organizations use in determining the success of a job evaluation plan. This is reflected in the increasing use of employees on job evaluation committees and in the communication that accompanies job evaluation implementation.

Keeping track of employee acceptance is a continuous process. One way of testing acceptance is a formal appeals process, whereby anyone questioning the evaluation of his or her job may request a reanalysis and reevaluation. Organizations would be wise to include such a process in their job evaluation system. A second option is to include questions about job evaluation in employee attitude surveys.

Reliability of Job Evaluation

A reasonable number of studies have been done on the reliability of job evaluation systems. Much of this has been concerned with whether job evaluation can or does lead to pay discrimination. In general, job evaluation has been shown to have high reliability. Variations in reliability occur due to both the type of plan and the particular factors used. One study showed point plans and classification plans more reliable than factor comparison or ranking.28 Point systems have proved reliable for inter-rate reliability, raters with a composite score and over periods of time. The reliability of factors varies. Skills, experience, and education are considered highly reliable, while responsibility, effort and working conditions rate lower.29

Research has found that job rating could be improved by a reduction in overlap among factors, good job descriptions, and rater training. Higher reliability also results when scale levels, including the use of benchmark jobs, are carefully defined. Familiarity with the jobs also seems to increase reliability.30 A study using a common point system confirmed the importance of training raters, but found that consensus rating by groups produced reliability rates as high as those of independent ratings in other studies. This study also found that non-interacting groups produced very similar ratings. Furthermore, it found that access to information beyond job descriptions improved the consistency of the ratings.31 These findings suggest that consistent ratings of jobs are not particularly susceptible to administrative conditions.

Validity of Job Evaluation

Validity is the measure of how well a measure, job evaluation in this case, measures what it is intended to measure. The criterion for job evaluation can be internal equity or the labor market. Studies that measure internal equity often measure how well a job evaluation system would classify a job into the grade where it has already been placed. The result of this is encouraging when job evaluation does classify the job where it has already been placed. This however, also brings up the question as to how we know the job is in its proper grade.32 The market as a criterion is useful assuming that pay competitiveness is the goal. If this is the case, then market pricing is the only thing needed and job evaluation is redundant. In fact, many job evaluation systems weight factors in such a way as to replicate the market. Using the market as a criterion has problems, just as does getting accurate data from salary surveys. As seen in Chapter 8, this is a definite challenge.33 A further way to approach the validity question is to compare the results of using different job evaluation plans. One such study found some evidence of convergent and discriminant validity, but that there were questionable areas such as some factors being better than others.34

While criterion-related validity may be questionable, an argument can be made that the face validity of job evaluation is good. The technique is accepted as a reasonable way to rate the relative worth of jobs by both managers and workers most of the time. One interesting method has been to validate Jaques Time Span method against employees' feelings regarding fair pay for their job. These studies show a high correlation between the two.35

Costs

Job evaluation involves costs of design and administration as well as onetime implementation costs. Labor-cost, design and administrative costs vary with the type of plan, the time spent by organization members, and by consulting fees (if any). Setting up a program has been estimated at 0.5 percent of payroll, and administering it, 0.1 percent per year.

Discrimination Issues

Although jobs and job evaluations are color-blind and have no inherent gender bias, job evaluation has been cited as both a potential source of, and solution for, discrimination against women and minorities. Discrimination may result from multiple job evaluation plans in the organization, from the choice or weighting of factors, and from stereotypes attached to jobs.

While more research is needed, the evidence so far does not establish the existence of discrimination in job analysis and job evaluation. A 1977 study found no evidence of gender discrimination in the use of the PAQ.36 A study at San Diego State University replicating the 1977 study but using other methods of job analysis found no gender bias either.37 Other studies, however, have found influence from gender stereotyping and gender composition of jobs.

The National Science Foundation study cited previously maintains that job evaluation may be a solution to problems of pay discrimination.38 But it suggests that single rather than multiple plans would help and that factors should represent all jobs and be defined without bias. It also suggests some ways of weighting factors to remove potential sex bias. These views will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 27.

SUMMARY

Job evaluation is the process by which the organization develops a job structure. The job structure is the hierarchy of jobs within the organization, ordered according to their value and importance to the organization. Job evaluation involves comparing jobs to each other or to a standard, and then ranking them by the standard of organizational importance.

Over 50% of the jobs in the U.S., as well as an increasing number of other countries, have their pay influenced by job evaluation. However, the popularity of job evaluation has declined in recent years. Changes in organizations away from rigid bureaucratic structures, have found job evaluation not to be a useful a tool. Many organizations are directly pricing jobs through market pricing. This goes to the heart of the organizational importance of pay as a competitive lever for business strategy.

The first decision to be made when developing a job evaluation plan, is to identify the factors that define the importance of the jobs in the organization, called compensable factors. The second is identifying the jobs that will be placed into the job evaluation plan (e.g. all jobs in the organization or some sub-set of jobs) defining the number of plans in the organization. The third is deciding what type of job evaluation plan will provide the organization with the best results. Here the organization has a number of choices that have been reviewed in this chapter.

Job evaluation plans are categorized as being either non-quantitative or quantitative. Non-quantitative plans, ranking or classification, (1) rate the job as a whole, (2) clearly rely on the judgments of the evaluator, and (3) are generally simpler and more flexible. These non-quantitative plans are used mainly in small organizations and governmental units. Quantitative plans, factor comparison and point factor, evaluate the job by the using a set of factors. These are more difficult to set up, provide a basis for determining their accuracy, and are more popular in industry.

Job evaluation has a basic dilemma. On one hand, it is a technical function that requires training and expertise to perform. On the other hand, the usefulness of job evaluation depends on the acceptance by management and employees of the job structure that results from the process. The best way to obtain acceptance is to allow managers and employees a role in the decision making that creates the job structure. Too often, job evaluation is seen by managers and employees as some mysterious, incomprehensible process that has a considerable impact on their wages.

APPENDIX

Market Pricing

Market pricing depends upon the use of salary surveys. This was the topic of Chapter 11. Obtaining and evaluating salary surveys is the important first step in designing a market price based salary structure system. The discussion in Chapter 8 on evaluating salary surveys needs to be followed to have an accurate market price based salary structure program. Salary surveys need to match the jobs, industry, and geographical region of your organization. In addition, think about these questions:

- From which markets do we hire employees?

- To what markets [organizations] do we lose employees?

- In which markets would we like to compete?

Once the salary surveys are chosen, the following steps need to be taken:

-

Select jobs to be priced. The more jobs in the organization that can be included, the easier it is to create a valid

job structure.

The requirements for jobs to be included are:

- Importance to the organization

- Comparable job in salary surveys

- Determine job comparability. Each internal job description needs to be compared with the benchmark job description in a salary survey for comparability. This process is often called leveling. This is an extremely important step. Pricing data when the jobs do not match, leads to jobs being placed incorrectly in the hierarchy.

- Collect the pricing data from the salary survey. This includes base pay, bonuses and other incentive pay as well as any information on benefits. This data needs to be adjusted to the time in which you are making the decisions. These processes were discussed in Chapter 8.

- Match jobs so that a price is attached to each one. Segmenting the organization’s jobs into job families and ranking them from high to low, or vice versa, makes the process more logical and easy, since at this point all you have is unorganized jobs with market rates attached.

- Next, the benchmarked jobs and non-benchmark jobs should be grouped into grades. This process is explained in Chapter 12.

- Non-benchmark jobs, those for which there is no market equivalent, are assigned to the structure by slotting or some alternative job evaluation technique.

See Parus for further information on market pricing.39

Ranking System

Developing a job ranking consists of the following steps:

- Obtain Job Information. As we have noted, the first step in job evaluation is job analysis. Job descriptions are prepared or secured if already available.

- Select Raters and Jobs to Be Rated. Raters who will attempt to make unbiased judgments are selected and trained in the rating procedure. Less training is required for ranking than for other methods of job evaluation. If job descriptions are available, it is unnecessary to select as raters only those people who know all the jobs well; this is probably impossible except in very small organizations. If all the jobs in the organization are to be ranked, it may be wise to start with key jobs. Another approach is to rank jobs by department and later combine the rankings.

- Select Compensable Factor(s). Although ranking is referred to as a "whole-job" approach, different raters may use different attributes to rank jobs. If judgments are to be comparable, compensable factors must be selected and defined. Even as broad a factor as job difficulty or importance is sufficient, so long as it is carefully defined in operational terms. Seeing that raters understand the factors on which jobs are to be compared, will help ensure that rankings are made based on those factors.

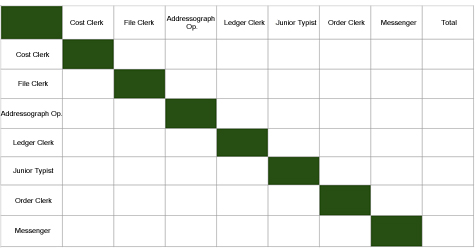

- Rank Jobs. Although straight ranking is feasible for a limited number of jobs (20 or less), alternation ranking, or paired comparison tends to produce more consistent results. Straight ranking involves ordering cards (one for each job) on which job titles or job summaries have been written. In case more information is needed by raters, it is useful to have the actual job description at hand. Alternation ranking provides raters with a form on which a list of job titles to be ranked are recorded at the left, and an equal number of blanks appear at the right. The raters are asked to record at the top of the right-hand column the job title they adjudge the highest, and also cross out that title in the list to the left. Then they record the lowest job in the bottom blank and continue in this manner with the remaining jobs in between, crossing out the job titles from the left-hand list along the way. In paired comparison, raters compare all possible pairs of jobs. One way to do this is with a pack of cards on which job titles have been recorded, as in straight ranking. Raters compare each pair of jobs at least once. The card of the job adjudged higher is checked after each comparison. After all comparisons have been made, the raters list the jobs, starting with the job with the most check marks and ending with the job with the least. A similar approach is to use a matrix like the one in Figure 11-2. For each cell in the matrix, the raters provide a check if the job listed on the left is higher than its counterpart on the top. The number of times a job is checked (tabulated in the "Total" column on the right) indicates its rank. Although this method of comparing pairs of jobs is less cumbersome, the number of comparisons increases rapidly with the number of jobs. The number of comparisons may be computed as (n)(n – 1) ÷ 2.

- Combine Ratings. It is advisable to have several raters rank the jobs independently. Their rankings are then averaged, yielding a composite ranking that is sufficiently accurate.

Job Classification System

Classification methods customarily employ a number of compensable factors. These typically emphasize the difficulty of the work, but also include performance requirements. The terms used in grade descriptions to distinguish differing amounts of compensable factors create a necessity for judgments to be made. For example, distinguishing between simple, routine, varied, and complex work and between limited, shared, and independent judgment is not automatic. While the judgment involved in such distinctions may produce the flexibility just cited as an advantage, it may also encourage managers to use inflated language in job descriptions and job titles to manipulate the classification of jobs. Developing a job classification system requires these steps:

- Obtain Job Information. If it is to function properly, classification, like all other job evaluation methods, must start with job analysis. A description is developed for each job. Sometimes key jobs are analyzed first and their descriptions used in developing grade descriptions; then the other jobs are analyzed and graded.

- Select Compensable Factors. Job descriptions are reviewed to distill factors that distinguish jobs at different levels. This is often done by selecting key jobs at various levels of the organization, ranking them, and seeking the factors that distinguish them. Obviously, the factors must be acceptable to management and employees.

- Determine the Number of Classes. The number of classes selected depends upon tradition, job diversity, and the promotion policies of the organization. Organizations tend to follow similar organizations in this decision. Those favoring more classes argue that more grades mean more promotions and employees approve of this. Those favoring fewer classes argue that fewer grades permit more management flexibility and a simpler pay structure. Obviously, diversity in the work and organization size increases the need for more classes.

- Develop Class Descriptions. This is a matter of defining classes in sufficient detail to permit raters to readily slot jobs. Usually this is done by describing levels of compensable factors that apply to the jobs in a class. Often, titles of benchmark jobs are used as examples of jobs that fall into a grade. Writing grade descriptions is more difficult if one set of classes is developed for the entire organization, than if separate class hierarchies are developed for different occupational groups. More specific class description eases the task of slotting jobs, but also limits the number of jobs that fit into a class. A committee is usually assigned the writing of class descriptions. It is often useful to write the descriptions of the two extreme grades first, then those of the others.

- Classify Jobs. The committee charged with writing grade descriptions is often also assigned the task of classifying jobs. This involves comparing job descriptions with class descriptions. The result is a series of classes, each containing a number of jobs that are similar to one another. The jobs in each class are considered to be sufficiently similar to have the same pay. Jobs in other classes are considered dissimilar enough to have different pay. Classification systems have been used more in government organizations than in private ones. Most are designed to cover a wide range of jobs and are based on the assumption that jobs will be relatively stable in content. Although classification tends to produce more defensible and acceptable job structures than ranking, it may substitute flexibility for precision. It is easy to understand and communicate, but its results are non-quantitative.

Factor Comparison Plans

Several variations in the basic method of factor comparison have appeared in response to one or more of the disadvantages of the basic system. Understanding these modifications requires an understanding of the basic method. For that reason, it is discussed first.

- Analyze Jobs. As in other job evaluation methods, the first step is to secure job information. Sometimes only key jobs are analyzed prior to construction of the job-comparison scale. But all jobs to be evaluated are eventually subjected to job analysis. Job descriptions are written in terms of the five universal factors. Note that the factors and their definitions govern the job description. For this reason, the organization will want to determine if its jobs can be described in these terms. It will do this by analyzing some key jobs and deriving compensable factors.

- Select Key Jobs. With job information at hand, the job evaluation committee selects 15 to 25 key jobs. This step is critical because the entire method is based upon these jobs. The major criterion for selection, as we have noted, is the essential correctness of the pay rate. However, the jobs should represent the entire range of jobs to be evaluated and be stable in content.

- Rank Key Jobs. Next, key jobs are ranked on each of the five factors. Committee members individually rank the jobs and then meet as a committee to determine composite ranks. These jobs are called tentative key jobs. They remain tentative until they are eliminated in later steps or become "true" key jobs.

- Distribute Pay Rates Across Factors. The next step is to decide, for each key job, how much of its pay rate should be allocated to each factor. This should be done individually and the results merged into one committee allocation.

- Compare Vertical and Horizontal Judgments. This involves crosschecking the judgments in steps 3 and 4. If a key job is assigned the same position in both comparisons, the judgments reinforce each other. If they do not, that job is not a true key job. Making this comparison may involve ranking the pay distribution as well, and then comparing the two ranks. This table identifies jobs that are not true key jobs, allowing them to be eliminated from the scale; and it indicates adjustments in the money distribution that would permit sufficient similarity in rankings to retain a job as a benchmark.

- Construct the Job-Comparison Scale. The job comparison scale incorporates the corrected pay distribution allocations to the key jobs (For an example, see Figure 11-3).

- Use the Job-Comparison Scale to Evaluate the Remainder of the Jobs. This is done by comparing the job descriptions of non-key jobs, one factor at a time, with jobs on the scale to determine the relative position. The evaluated salary for each non-key job is the sum of the allocations to the five factors. Once evaluated, a non-key job becomes another benchmark to use in evaluating the balance of the jobs.

Variations of the Basic Method

We have seen that factor comparison concepts are used in other job evaluation plans. The potential bias from the use of pay units, for example, has been met by multiplying monetary values by some constant, resulting in points.

The Percentage Method

This is a more fundamental modification of basic factor comparison. It addresses the disadvantage of monetary units and may be used in case of doubt about the corrections of pay rates for key jobs. The percentage method employs vertical and horizontal comparisons of key jobs on factors, as does the basic method. In fact, the two methods are identical in their initial three steps. At this point percentages are assigned to the vertical rankings by dividing 100 points on each factor among the key jobs in accordance with their ranks. The money distribution in the basic method becomes a horizontal ranking of the importance of factors in each job. This ranking is also translated into percentages by dividing 100 points among the factors in accordance with their ranks. Comparison of vertical and horizontal percentages involves expressing each percentage as a proportion of a common base. Then either the horizontal or the vertical percentage for each factor in each job, or an average of the two, forms the basis of the job-comparison scale. In practice, the percentages recorded in the scale are usually adjusted from a table of equal-appearing intervals of 15 percent. Hay, who developed the percentage method, argued that 15 percent differences are the minimum observable in job evaluation.40 The job-comparison scale in the percentage method is a ratio scale (equal distances represent equal percentages), but is used in the same way as in the basic method.

Profiling

A profile is a distribution in percentage terms, of the importance of factors in a job. 100 percentage points are distributed in accordance with their horizontal rankings. This distribution is used like the percentage method already described.

The Use of Existing Pay Rates to Weight Factors

This can now be considered a concept derived from basic factor comparison. The well-known Steel Plan, for example, was developed by deriving factor (and degree) weights statistically, by correlating job rankings by factors with existing pay rates of key jobs.41

The Hay Guide Chart-Profile Method

This is the best-known variation of factor comparison. 42 It is described as a form of factor comparison for the following reasons: it uses universal factors, bases job values on 15 percent intervals, and makes job-to-job comparisons. The plan is tailored to the organization. Profiling is used to adjust the guide charts and to check on the evaluation of jobs. The plan may be used for all types of jobs and is increasingly used for all jobs in an organization.

The universal factors in the Hay plan are know-how, problem solving, and accountability. These three factors are broken down into eight dimensions. Know-how (skill) involves (1) procedures and techniques, (2) breadth of management skills, and (3) person-to-person skills. The two dimensions of problem solving are (1) thinking environment and (2) thinking challenge. Accountability has three dimensions: (1) freedom to act, (2) impact on results, and (3) magnitude. A fourth factor, working conditions, is sometimes used for jobs in which hazards, environment, or physical demands are deemed important.

The heart of the Hay Plan is its guide charts use of 15 percent intervals. Although these charts appear to be two-dimension point scales, the Hay Group insists that, except for the problem-solving scale, they may be expanded to reflect the size and complexity of the organization. It also states that the definitions of the factors are modified as appropriate to meet the needs of the organization.

Profiling is used to develop the relationship among the three scales and to provide an additional comparison with the points assigned from the guide charts. Jobs are assumed to have characteristic shapes or profiles in terms of problem-solving and accountability requirements. Sales and production jobs, for example, emphasize accountability over problem solving. Research jobs emphasize problem solving more than accountability. Typically, staff jobs tend to value both.

Implementation consists of (1) studying the organization and selecting and adjusting guide charts, (2) selecting a sample of benchmark jobs covering all levels and functions, (3) analyzing jobs and writing job descriptions in terms of the three universal factors, (4) selecting a job evaluation committee consisting of line and staff managers, a human resources specialist, employees, and a consultant, and (5) evaluating benchmark jobs and then all other jobs.

Point values from the three guide charts are added, yielding a single point value for each job. Profiles are then constructed and compared on problem solving and accountability, as an additional evaluation.

Note that the Hay plan is independent of the market. Also, an organization using the plan must rely heavily on an outside consultant for both implementation and management.

Point Factor Plans

The steps in building a point-factor plan are as follows:

- Analyze Jobs. As in all other job evaluation methods, this step comes first. All jobs may be analyzed at this point, or merely a sample of benchmark jobs to be used to design the plan. A job description is written for each job analyzed.

- Select Compensable Factors. When job information is available, compensable factors are selected. Although the yardsticks on which jobs are to be compared are important in all job evaluation methods, they are especially important in the point-factor method. Because a number of factors are used, they must be the ones for which the organization is paying.

- Define Compensable Factors. Factors must be defined in sufficient detail to permit raters to use them as yardsticks to evaluate jobs. Such definitions are extremely important because the raters will be referring to them often during their evaluations. When the factors chosen are specific to the organization, the task of defining them is less difficult. Also, it is often argued that definitions may be more precise when the plan is developed for one job family or function. There seems to be a growing tendency to define factors in more detail. See figure 11-4 for an example.

-

Determine and Define Factor Degrees. As we have noted, the rating scale for each factor consists of divisions called degrees. Determining these degrees would be like determining the inch marks on a ruler. It is necessary first to decide the number of divisions, then to ensure that they are equally spaced or represent known distances, and finally to see that they are carefully defined. The number of degrees depends on the actual range of the factors in the jobs. If, for example, working conditions are seen to be identical for most jobs, and if jobs that differ from the norm have very similar working conditions, then it is sufficient to have no degrees. If, on the other hand, seven or even more degrees are discernible, that number of degrees is specified.

A major problem in determining degrees is to make each degree equidistant from the two adjacent degrees. This problem is solved in part by selecting the number of degrees actually found to exist and in part by careful definition of degrees. Decision rules such as the following are useful:- Limit degrees to the number necessary to distinguish between the jobs.

- Use terminology that is easy to understand.

- Use standard job titles as part of degree definitions.

- Make sure that the applicability of the degree to the job is apparent.

-

Determine Points for Factors and Degrees. Only rarely are compensable factors assigned equal weight. It is usually determined that some factors are more important than others and should bear more weight.

Factor weights may be assigned by committee judgment or statistically. In the committee approach, the procedure is to have committee members (1) carefully study factor and degree definitions, (2) individually rank the factors in order of importance, (3) agree on a ranking, (4) individually distribute 100 percent among the factors, and (5) once more reach agreement. The result is a set of factor weights representing committee judgment. The weights thereby reflect the judgments of organization members and may contribute to acceptance of the plan.

The committee may then complete the scale by assigning points to factors and degrees. Next a decision is usually made on the total points possible in the plan – say 1000. Applying the weights just assigned to this total, yields the maximum value for each factor. For example, a factor carrying 30 percent of the weight has a maximum value of 300 points. Thus, the highest degree of this factor carries 300 points. Assigning points to the other degrees may be done by either arithmetic or geometric progression. In the former, increases are in equal numbers of points from the lowest to the highest degree. In the latter, increases are in equal percentage of points. Arithmetic progression is found in most point plans, especially those designed for one job family rather than the entire organization. But just as different factors usually have different numbers of degrees, some factors may employ geometric progression.

Because it is usually assumed that all jobs include some of a factor, the lowest degree is usually assigned some points. A simple way of assigning points to degrees is as follows:- Set the highest degree of a factor by multiplying the weight of the factor by the total possible points.

- Set the minimum degree of the factor using the arithmetic or percentage increase figure.

- Subtract these two figures.

- Divide the result by the number of steps (numbers of degrees minus one).

- Add this figure successively to the lowest degree.

In the statistical approach to weighting factors, benchmark jobs are evaluated, and the points assigned are correlated with an agreed-upon set of pay rates. Regressing this structure of pay rates on the factor degrees assigned each job yields weights that will produce scores closely matching the agreed-upon pay rates. Factor weights were developed statistically in the Steel Plan, which was mentioned in our discussion of factor comparison. The same approach is used to develop weights for factors derived from quantitative job analysis. The statistical approach is often called the policy-capturing approach.

Whether developed by committee decision or by the statistical method, the rating scales are often tested by evaluating a group of benchmark jobs. If the results are not satisfactory, several adjustments are possible. Benchmark jobs may be added or deleted. Degrees assigned to jobs may be adjusted. The criterion – the pay structure – may be changed; or the weights assigned to factors may be changed. In any of these ways, the job evaluation plan is customized to the jobs and the organization. - Write a Job Evaluation Manual. A job evaluation manual conveniently consolidates the factor and degree definitions and the point values (the yardsticks to be used by raters in evaluating jobs). It should also include a review procedure for cases where employees or managers question evaluations of certain jobs. Usually the compensation specialist conducts such reevaluations, but sometimes the assistance of the compensation committee is called for.

- Rate the jobs. When the manual is complete, job rating can begin. Raters use the scales to evaluate jobs. Key jobs have usually been rated previously in the development of the plan. The others are rated at this point. In smaller organizations, job rating may be done by a compensation specialist. In larger firms, committee ratings developed from independent ratings of individual members are usual. As jobs are rated, the rating on each factor is recorded on a substantiating data sheet. This becomes a permanent record of the points assigned to each factor and the reasons for assigning a particular degree of the factor to the job. Substantiating data come from the job description.

FACTOR: KNOWLEDGE

A. Formal Education: Considers the extent or degree to which specialized, technical or general education, as distinguished from working experience, is normally required as a minimum to proficiently perform the duties of the job. Credit for general education or technical and specialized training beyond high school must be carefully substantiated, that it is required and not merely preferred, and that it can be shown to be job related (what the education equips the job holder to do, not what the specific degree or course is).

B. Work Experience: Consider the minimum amount of experience normally required on the job and in related or lower jobs, for an average qualified applicant to become proficient.