Chapter 10: Job Analysis

Overview: This chapter describes job analysis, why it's an essential part of Human Resource Management, the types of job analysis, and the process for conducting a job analysis and developing job descriptions.

Corresponding courses:

33 Job Analysis and Job Descriptions

INTRODUCTION

Organizations are created to accomplish some goal or objective. They are made up of groups or teams and not individuals because achieving the goals requires the efforts (work) of a number of people (workers). The point where the work and the employee's role come together in the organization is called a job. We need to know a lot of information about these roles/jobs, such as:

- What does or should the person do?

- What knowledge, skill, abilities, and behaviors does it take to do this job?

- What is the result of the person performing the job?

- How does this job fit in with other jobs in the organization?

- What is the contribution of this job toward the organization’s goals?

Information about jobs is obtained through a process called job analysis.

Job analysis is the series of activities undertaken to systematically obtain, categorize, and document all relevant information about a specific job.

The goal of this process is to secure whatever job data are needed for the specified Human Resource Function, such as job evaluation.

USES OF JOB ANALYSIS

This knowledge about jobs is used for many purposes, certainly in the field of Human Resource Management (HRM). In particular, where the job is the basis for pay, knowledge of the job is essential either to make comparisons with other jobs in market pricing or as the first step in evaluating jobs internally. Thus, failure to secure complete and accurate job information will result in inaccurate salary determination. Later steps in job evaluation become virtually impossible without adequate job information.

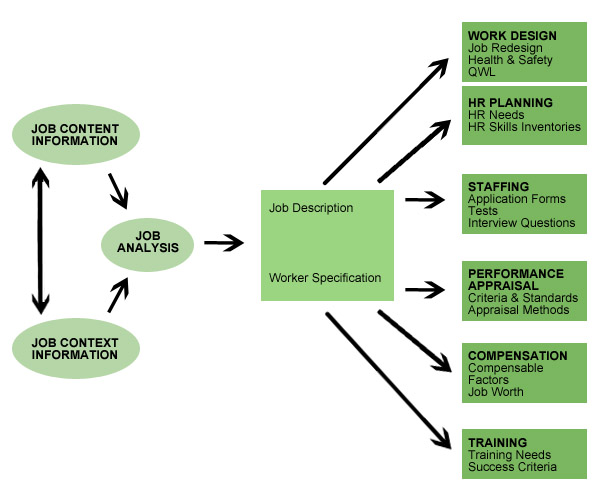

Job knowledge has many uses in HRM. Organizations use information obtained by job analysis for recruitment, selection, and placement; organization planning and job design; training; grievance settlement; as well as job evaluation and other compensation programs. This centrality of job analysis is illustrated in Figure 10-1.

People outside the organization also use information about jobs. Career placement requires the same type of person-job matching that organizations do. Getting a disabled worker back to work requires knowledge of jobs in order to determine what jobs the worker can do or can be trained to do. Lastly, job knowledge is needed in a number of regulatory situations as will be discussed later in this chapter.

(QWL in the graphic refers to Quality Work Life.)

Source: Adapted from J. Ghorpade (1988). Job analysis: A handbook for the HR director.

Englewood cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, p. 6

These different uses of job information may require specialized job descriptions. Job evaluation requires information that permits distinguishing jobs from one another, usually on the basis of work activities and/or job required worker characteristics. Recruitment and selection require information on the human attributes a successful jobholder must bring to the job. Training requires information on the knowledge and skills that the successful jobholder must demonstrate. Job design may require identifying employee perceptions of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. Although there is overlap among these different requirements, arguments for separate job analysis for separate purposes are understandable.1

HISTORY OF JOB ANALYSIS

Job analysis as a management technique was developed around 1900.2 It became one of the tools managers used to understand and direct organizations. Frederick W. Taylor, through his interest in improving the efficiency of work, made studying the job one of his principles of scientific management.3 From his ideas emerged time and motion study of jobs. Early organization theorists were interested in how jobs fit into organizations: they focused on the purpose of the job.4 But this early interest in job analysis disappeared as the human relations movement focused on other issues. It was not until the 1960s that psychologists and other behavioral scientists rediscovered jobs as a focus of study in organizations.

The organization with the greatest long-term interest in job analysis has been the United States Department of Labor (DOL). The United States Employment Service (USES) of the DOL's Training and Employment Administration has developed job analysis procedures and instruments over many years. These procedures probably represent the strongest single influence on job analysis practice in the United States. The DOL's Guide for Analyzing Jobs and Handbook for Analyzing Jobs show the development of job analysis procedures over almost 50 years.5 They developed and published The Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT)6, and they have a policy of helping private employers install job analysis programs. The DOL has led development of the conventional approach to job analysis.

The U.S. Department of Labor's last complete update of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles was in 1977 with 12,741 positions described (a minor update was released in 1991). No further government releases are planned as O*NET and its Standard Occupation Classification (SOC) codes have replaced the "DOT" in its entirety. ERI has updated the abandoned U.S. DOT. New job descriptions have evolved from ERI's analysis of thousands of salary surveys. Job analysis work fields, skills, MSPMS (Materials/Products/Subject Matter/Services), and worker specific occupational characteristics, including new stress measures, are added, updated, and/or enhanced for more than 26,000 position descriptions.

Up to this point, job analysis had focused upon the work being done. In the 1970's this changed as psychologists became interested in job analysis. Their contribution was in three areas. The first is in quantifying job analysis. They began to develop questionnaires to collect data on jobs. Second, they contributed to the trend toward a worker orientation to job analysis. Third, they focused in some cases on units smaller than the job, such as the task or elements within jobs.7

Equal Pay Act

More recently the interest in job analysis has been based on the passage of civil rights legislation. Job analysis is required in the field of staffing since any predictor used to select a person must be job-relevant. Determining job relevance requires having knowledge of what is happening in the job, usually through job analysis. Likewise, in compensation, the requirements of the Equal Pay Act requires jobs that are substantially similar to be paid the same. The determination that two jobs are substantially similar is done through job analysis.

Americans with Disabilities Act

Perhaps the major legal reason for conducting job analysis in organizations is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This act requires employers to consider for hire or continued employment any person who can perform the "essential elements" of the job. The act assumes that if the person can perform the essential tasks or elements of the job, then the employer can provide "reasonable accommodation" to the employee so that he or she can perform the job. Since the passage of the act, many organizations have begun to place in all job descriptions a statement of the job’s essential tasks or elements. This aids in hiring and placement decisions.

APPROACHES TO ANALYZING JOBS

There is no one way to study jobs. Many models of job analysis now exist, each focusing on some particular use for job analysis. The process may seek to obtain information about:

- The work

- The worker

- The context within which the job exists

Further, the approach may be either inductive or deductive. In an inductive approach, information about a job is collected first, then organized into a framework to create a description of a job. In a deductive approach, a model of the information is developed, and the collection of data focuses upon this model.

The job analysis formula first outlined by the DOL in 1946 is a simplified but complete model of obtaining information on work activities. The formula consists of (1) what the worker does, (2) how he or she does it, (3) why he or she does it, and (4) the skill involved in doing it. In fact, providing the what, how, and why of each task constitutes the total job resulting in a functional description of work activities for compensation purposes.

By 1972, however, this formula had been expanded by the DOL to encompass five models as described in Figure 10-2. Note that work activities in the 1946 formula become worker behaviors identified through the use of functional job analysis.8 Models 2 and 3 are elaborations of the how question in the original format. The fourth model is an elaboration of the why (purpose) question in the original formula. Finally, worker traits or characteristics represent an additional type of job information.

- Worker Functions. The relationship of the worker to data, people, and things.

- Work Fields. The techniques used to complete the tasks of the job. Over 100 such fields have been identified. This descriptor also includes the machines, tools, equipment, and work aids that are used in the job.

- Materials, Products, Subject Matter, and/or Services. The outcomes of the job or the purpose of performing the job.

- Worker Traits. The aptitudes, educational and vocational training, and personal traits required of the worker.

- Physical Demands. Job requirements such as strength, observation, and talking. This descriptor also includes the physical environment of the work.

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Handbook for Analyzing Jobs (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1972).

Thus the 1972 approach implies that the job information changed from work activities (tasks) to worker behaviors. It also suggests that the how and why of work activities (but not the work activities themselves) are more important. Finally, worker characteristics are added to the job information required. Worker behaviors (functions), work fields, tools, and products and services represent work performed.

In comparison McCormick, in his Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ), develops a model that classifies job descriptors as follows:

- work activities

- job-oriented activities

- worker-oriented activities

- machines, tools, equipment

- work performed

- job context

- personnel requirements9

This classification suggests that job analysis can yield six kinds of useful job information. These descriptors presumably flow from McCormick's model of the operational functions basic to all jobs, sensing (information receiving), information storage, information processing, and decision and action (physical control or communication). These functions vary in emphasis from job to job.

Richer suggests that the following job information is needed by organizations: (1) job content factors; (2) job context factors; (3) worker characteristics; (4) work characteristics; and (5) interpersonal relations (internal and external).10 This model focuses more on the contextual aspects of the job than the other two.

These and other methods of job analysis will be reviewed later in this chapter.

Dimensions of job analysis

There are a multitude of job analysis methods. These methods differ on a number of dimensions. We will examine:

- The level of analysis

- The information to be collected

- Methods of collecting information

- Sources of information

Level of Analysis

By titling the concept we are discussing, job analysis, we imply that the unit of analysis is the job. Actually, the level or unit of analysis represents a decision that is worthy of discussion.

The lowest level is employee attributes, the knowledge, skills, and abilities required by the job.11 Some of the models discussed in the previous section suggested this level of descriptor.

One level up is the element. An element is often considered the smallest division of work activity apart from separate motions, although it may be used to describe singular motions. As such, it is the unit of analysis for time and motion study and is used primarily by industrial engineers.

The next level is the task, a discrete unit of work performed by an individual. A task is a more independent unit of analysis. It consists of a sequence of activities that completes a work assignment.

When sufficient tasks accumulate to justify the employment of a worker, a position exists. There are as many positions as employees in an organization.

A job is a group of positions that are identical in their major or significant tasks. The positions are sufficiently alike, in other words, to justify being covered by a single analysis and description. One or many persons may be employed on the same job.

Jobs found in more than one organization are termed occupations.

Finally, occupations grouped by function are usually referred to as job families.

Obviously, the level or unit of analysis chosen may influence the decision of whether the work is similar or dissimilar. By law (the Equal Pay Act of 1963), if jobs are similar, both sexes must be paid equally; if jobs are different, pay differences may exist.

As suggested in the previous section, the unit of analysis used differs among organizations. Although the procedure is called job analysis, organizations using it may collect data at several levels of analysis. Research has shown that jobs can be similar or dissimilar at different levels of analysis.12 The more detailed the analysis, the more likely that differences will be found.

Information to be Collected

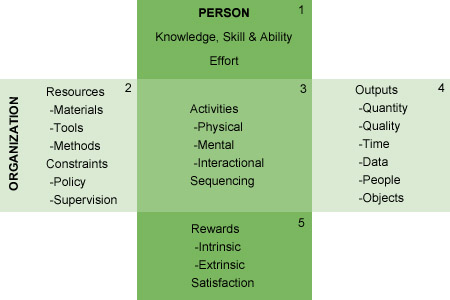

Since the job is the connection between the organization and the employee, it may be useful to develop a model based upon this common connection. We can say that both the organization and the employee contribute to the job and expect to receive something from it. In order for these results to come about, something has to happen inside the job. This dual systems-exchange model is illustrated in Figure 10-3.

The vertical dimension of the model is the person-job relationship. The person brings his or her knowledge, skills and abilities as well as effort to the job (cell 1). These are used in activities, which are divided into physical, mental, and interactional types (cell 3). The results, for the person, are the rewards and satisfaction received from working on the job (cell 5). These rewards can be both intrinsic and extrinsic. The latter are the basic subject of this book.

The horizontal dimension of the model is the organization-job relationship. The organization brings to the job resources needed to perform the job and ways to do the job that coordinate with organizational needs; the latter are perceived as constraints (cell 2). These resources and constraints determine the way the job activities (cell 3) are carried out. The organizational results are some product created or service performed by the employee; these outcomes are in the form of a change in data, people, and/or objects (cell 4). These results can be defined in terms of quantity, quality, and time.

This model suggests that information (descriptors of jobs) can be collected on the purpose of the job (cell 4), the activities of the job (cell 3), the worker requirements of the job (cell 1), the organizational context of the job (cell 2), and the rewards of the job to the worker (cell 5).

Responsibilities and Duties. We should not leave this section on information to be collected without a word about two commonly used terms, responsibilities and duties. While job descriptions are often organized around these concepts, we feel that they are not useful terms in identifying job content. Both terms move the analyst away from thinking about what is done and how. When done well, descriptions of duties and responsibilities describe why work is done adequately (cell 4). But few of these descriptions do even this well. This leaves the job incumbent with some vague statement about why he or she is doing something, but little knowledge of what it is or how to do it (cell3). Determining performance levels becomes difficult. And the job evaluator has a collection of words that provide little help in determining the relative worth of jobs in the organization. Adjectives then become the main determinant of job level. It is this kind of job description that has led many human resources directors to decry the futility of job analysis and job descriptions.

Methods and Sources of Job Information

Probably the most common picture that comes to mind when one thinks about collecting job information is that of an analyst interviewing a job incumbent. This is indeed a common way in which job information is collected, but it is far from the only way. The best interviews are those in which the analyst has prepared by examining organization data as well as any past descriptions of the job. A related technique would be to observe the job incumbent performing the job. This technique is most successful for jobs that are physical in nature. The interview or observation may be totally inductive, one in which the analyst has no preconceived idea about the job to a very structured situation in which the analyst has a clear pro forma as to the information sought.

While these one-on-one techniques may be the most common, it is not the only way for an analyst to obtain information directly from others. Of increasing popularity are group-based techniques. Such groups may consist of any of the following:

- Knowledgeable incumbents

- Supervisors

- Technical experts, such as Industrial engineers or organization analysts

- Others that deal with the incumbents of the job.

Any combination of these groups may be used, for instance in a manner similar to a 360 degree performance appraisal.

The advantage of using groups is to collect a large amount of information rapidly as well as providing help in integrating the information. However, using groups can be costly, and getting the group together may be difficult.13

A more typically structured technique is that of a questionnaire. This may be used by the job analyst in an interview but is more typically completed by the incumbent without such aid. Preparation of a questionnaire takes time and skill of individuals knowledgeable of both the jobs and questionnaire preparation. Questionnaires may be a computer-based program, either designed specifically for the organization or a more general one used to collect information from a large number of people working in many different organizations.

Lastly, the organization has a variety of information that is useful for gathering information about specific jobs, particularly the job context. These may be:

- Policies and procedures manuals

- Other records, such as performance appraisals, old job descriptions, correspondence regarding the job, information about work output

- Literature regarding the job, both from within the organization and outside the organization

- Where equipment plays a large part of the job, the design specifications.14

A Note on Job Analysts

Employees, supervisors, and job analysts perform the tasks of collecting and analyzing job information. Job incumbents have the most complete and accurate information, but getting this information and making the results consistent requires attention to data-collection methods. Also, employee acceptance of the results is a priority, and employee involvement in data collection and analysis tends to promote this.

Supervisors may or may not know the jobs of their subordinates well enough to be useful sources of job information. If they do know the jobs well enough, a great deal of time and money can be saved.

Job analysts have been trained to collect job information. They know what to look for and what questions to ask. They also know how to standardize the information and the language employed. People with various educational backgrounds have been trained as job analysts. Most organizations train their own job analysts by having them work with experienced analysts.

Some organizations give new staff job analyst assignments. This approach permits new incumbents to learn about the organization's work and creates a pool of trained analysts.

When supervisors and job incumbents are used in job analysis, some training is required. As repeatedly emphasized, involvement by employees and supervisors increases the usefulness and acceptance of the data including personnel processes which use these data.

JOB ANALYSIS METHODS

There are many job analysis methods. In this section we will review some of the more popular approaches to job analysis or ones that represent a particular approach. These job analysis methods differ in descriptors, levels of analysis, and methods of collecting, analyzing, and presenting data. We will evaluate these approaches in terms of purpose, descriptor applicability, cost, reliability, and validity.

Conventional Procedures

Conventional job analysis programs typically involve collecting job information by observing and/or interviewing job incumbents. Then job descriptions are prepared in essay form. Much of the conventional approach comes from the long experience of the United States Employment Service in analyzing jobs. As mentioned previously, the original job analysis formula of the DOL provided for obtaining work activities. The DOL's 1972 revision of this schedule requires the job title, job summary, and description of tasks (these were referred to as work performed in the 1946 formula), as well as other data.

Conventional job analysis treats work activities as the primary job descriptor. As a consequence, the use of the conventional approach by private organizations focuses largely on work activities rather than on the five types of descriptors used in the DOL job analysis schedule (Figure 10-2).

Because job evaluation purports to distinguish jobs on the importance of work activities to the employing organization, this descriptor seems primary. As we noted, using the DOL's original job analysis formula (what the worker does, how the worker does it, and why the worker does it) may provide reasonable assurance that all the work activities are covered. One of the functions of this model is to require the analyst to seek out the purpose of the work.

In some modified use of the conventional approach, worker job attributes are also collected. Ratings of education, training, and experience required may be obtained, as well as information on contacts required, report writing, decisions, and supervision. In part, these categories represent worker attributes, and in part they represent a search for specific work activities.

Some conventional job analysis programs ask job incumbents to complete a preliminary questionnaire describing their jobs. The purpose is to provide the analyst with a first draft of the job information needed. It is also a first step in obtaining incumbent and supervisor approval of the final job description. Of course, not all employees enjoy filling out questionnaires. Also, employees vary in verbal skills and may overstate or understate their work activities. Usually, the job analyst follows up the questionnaire by interviewing the employee and observing his or her job.

Reliability and Validity. Conventional job analysis is subjective. It depends upon the objectivity and analytical ability of the analyst as well as the information provided by job incumbents and other informants. Measuring reliability (consistency) and validity is difficult because the data are non-quantitative. Having two or more individuals analyze the job independently would provide some measure of reliability but would also add to the cost. Perhaps the strongest contributor to both reliability and validity is the common practice of securing acceptance from both job incumbents and supervisors before job descriptions are considered final. These procedures develop a content validity for job descriptions.

Costs. Conventional job analysis takes the time of the analyst, job incumbents, and whoever is assigned to ensure consistent analysis and form. In the authors' experience, people with moderate analytical skills can be taught to analyze jobs on the basis of the job analysis formula (what, how, why) in a few hours.

An early survey found some dissatisfaction with conventional job analysis, especially with its costs and with the difficulty of keeping the information current.15 McCormick's review of job analysis, while concluding that the continued use of conventional methods testifies that they serve some purposes well, suggests more attention to a comprehensive model and more quantification.16

As suggested earlier in the chapter, work activities represent the primary descriptor in job analysis for job evaluation purposes. However, these data take considerable effort to obtain and have questionable reliability. It would be desirable to develop a standardized quantitative approach that retains the advantages of conventional job analysis, while permitting a less costly and time-consuming approach.

Position Analysis Questionnaire

Probably the best known quantitative approach to job analysis is the Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ) developed by McCormick and associates at Purdue University. The PAQ is a structured job analysis questionnaire containing 194 items called job elements.17 These elements are worker-oriented; using the terminology of the DOL's 1972 job analysis formula; they would be classified as worker behaviors. The items are organized into six divisions:

- information input,

- mental processes,

- work output (physical activities and tools),

- relationships with others,

- job context (the physical and social environment), and

- other job characteristics (such as pace and structure).

Each job element is rated on six scales: extent of use, importance, time, possibility of occurrence, applicability, and a special code for certain Jobs.

The PAQ is usually completed by job analysts or supervisors. In some instances, managerial, professional, or other white-collar job incumbents fill out the instrument. The reason for such limitations is that the reading requirements of the method are at least at the college-graduate level.

Data from the PAQ can be analyzed in several ways. For a specific job, individual ratings can be averaged to yield the relative importance of and emphasis on various job elements, and the results can be summarized as a job description. The elements can also be clustered into a profile rating on a large number of job dimensions to permit comparison of this job with others. Estimates of employee aptitude requirements can be made. Job evaluation points can be estimated from the items related to pay. Finally, an occupational prestige score can be computed. Analysts can have PAQ data computer-analyzed by sending the completed questionnaire to PAQ Services.

The PAQ has been used for job evaluation, selection, performance appraisal, assessment-center development, determination of job similarity, development of job families, vocational counseling, determination of training needs, and job design. For more complete information about the use of the PAQ, go to: www.erieri.com/paq.

Reliability and Validity. The PAQ has been shown to have a respectable level of reliability. An analysis of 92 jobs by two independent groups yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.79.18

If our earlier analysis of job descriptors is correct, in spite of the successful use of the PAQ for job evaluation purposes, its use of worker behaviors instead of work activities as descriptors may limit its acceptability to employees. Also, when used in job evaluation, its lack of employee involvement, as well as its use of only 9 of the 194 job elements may limit its acceptability.

Functional Job Analysis

Functional Job Analysis (FJA) is usually thought of in terms of the familiar "data, people, things" hierarchies used in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. Developed by Sidney A. Fine and associates, this comprehensive approach has five components:

- identification of purposes, goals, and objectives,

- identification and description of tasks,

- analysis of tasks on seven scales, including three worker-function scales (one each for data, people, and things) See figure 10-4,

- development of performance standards, and

- development of training content.19

| DATA | PEOPLE | THINGS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Synthesizing | 0 Mentoring | 0 Setting Up | ||

| 1 Coordinating | 1 Negotiating | 1 Precision Working | ||

| 2 Analyzing | 2 Instructing | 2 Operating-Controlling | ||

| 3 Compiling | 3 Supervising | 3 Driving-Operating | ||

| 4 Computing | 4 Persuading | 4 Manipulating | ||

| 5 Copying | 5 Speaking-Signaling | 5 Tending | ||

| 6 Comparing | 6 Serving | 6 Feeding-off Bearing | ||

| 7 Taking Instructions | 7 Handling -Helping |

FJA data are developed by trained job analysts from background materials, interviews with workers and supervisors, and observation. The method provides data for job design, selection, training, and evaluation and could be used at least partially for most other personnel applications. It has been applied to jobs at every level.

The major descriptor in FJA is work activity. A number of task banks have been developed by Fine and his colleagues as a means of standardizing information on this descriptor. FJA is rigorous, but it does require a heavy investment of time and effort.20

Comprehensive Data Analysis Program [CODAP]

The Comprehensive Data Analysis Program [CODAP] is a major example of the task inventory approach to job analysis. The emphasis of this approach is on work activities. Task inventories develop a list of tasks pertinent to a group of jobs being studied. Then the tasks involved in the job under study are rated on a number of scales by incumbents or supervisors. Finally the ratings are manipulated statistically, usually by computer, and a quantitative job analysis is developed. Actually, any method of job analysis, even narrative job descriptions, could be termed a task inventory if an analysis of the data can provide quantitative information from appropriate scales. CODAP is undoubtedly the best-known task inventory. It was developed over many years by Raymond E. Christal and his associates for the United States Air Force.21 The heart of the program is a list of tasks involved in a particular job. After the task list has been prepared by incumbents, supervisors, or experts, incumbents are asked to indicate whether they perform each of the tasks. They are then asked to indicate on a scale the relative amount of time spent in performing each particular task. Other ratings are also obtained, such as training time required and criticality of performance.

The ratings are then summed across all tasks, and an estimated percentage of time on each task is derived. The total percentages account for the total job. The relative times are then used to develop a group job description.

Computer programs are used to analyze, organize, and report on data from the task inventory. The programs are designed to provide information for a variety of applications. For example, the CODAP can describe the types of jobs in an occupational area, describe the types of jobs performed by a specified group of workers, compare the work performed at various locations or the work performed by various levels of personnel, and produce job descriptions. The program can process data on 1,700 tasks for each of 20,000 workers.

The CODAP is most useful for large organizations and is relatively costly. The descriptor employed is work activities, and the output of the analysis is the work performed. Worker requirements must be inferred, as in conventional job analysis. Data developed by this method have been used in selection to identify training needs and design training programs, to validate training completion as a training criterion, to restructure jobs, and to classify jobs. The CODAP is used in all branches of the United States military, federal government, and some local governments.

Like most computer-driven systems, the technique is as good as the input. Computer analysis cannot correct for inaccurate or incomplete information. Using trained personnel to develop inventories of specific tasks is therefore a requirement of the method. Given a complete and accurate task inventory, statistical analysis of the distribution of the ratings provides some indications of reliability and validity.

Occupational Information Network [O*Net]

The O*NET system is supposedly designed to supersede the sixty-year-old Dictionary of Occupational Titles. The system uses a common language and terminology to describe occupational requirements, with current information that can be accessed online or through a variety of public and private sector career and labor market information systems.22 The O*NET system, which was significantly upgraded and improved in November 2003, includes the O*NET database, and the O*NET OnLine.

O*NET Database. The O*NET database is a comprehensive source of descriptors, with ratings of importance, level, frequency, or extent, for more than 950 occupations that are key to our economy. The new O*NET 5.1 database represents a major milestone, adding new data collected directly from job incumbents for over 50 occupations. O*NET descriptors include:

- skills,

- abilities,

- knowledge,

- tasks,

- work activities,

- work context,

- experience levels required,

- job interests, and

- work values/needs.

Each O*NET occupational title and code is based on the most current version (2000) of the Standard Occupational Classification System. This ensures that O*NET information links directly to other labor market information, such as wage and employment statistics. A Spanish translation of the O*NET database, developed by a special team from Aguirre International, is now available. The O*NET data files are available as free downloads. Click on the Developer's Corner at online.onetcenter.org.

O*NET OnLine. O*NET OnLine is a web-based viewer that provides easy public access to O*NET information. With the O*NET 5.1 database, users have access to new and updated data unavailable before. Using O*NET OnLine, students, job seekers and workforce, business, and human resource professionals can: find occupations to explore, search for occupations that use designated skills, view occupation summaries and details, use crosswalks from other classification systems to find corresponding O*NET occupations, view related occupations, create and print customized reports outlining their O*NET search results, and link to other online information resources. O*NET OnLine offers universal accessibility through a single online site that is 508 compliant for disabled users. O*NET OnLine has screen reader compatibility built in and users can adjust font size on all screens. O*NET OnLine links directly to pay and employment outlook information through America's Career InfoNet. OnLine Help provides user-friendly information and can be accessed from any screen. Get O*NET OnLine.

Clearly the O*NET is not a replacement for the DOT. It surveys 950 occupations as opposed to over 9,000 jobs covered in the DOT. Most importantly, and as made clear in the preceding paragraphs, the focus of the O*NET is not the job, but the occupation. For occupational analysts, it is a wonderful tool, but for the job analyst, it is not as useful unless he or she is surveying a wide range of jobs in a particular occupation.

JOB DESCRIPTIONS

Regardless of who collects job information and how they do it, the end-product of job analysis is a standardized job description. A job description describes the job as it is being performed. In a sense, a job description is a snapshot of the job at the time it was analyzed. Ideally, they are written so that any reader, whether familiar or not with the job, can "see" what the worker does, how, and why. What the worker does describes the physical, mental, and interactional activities of the job. How deals with the methods, procedures, tools, and information sources used to carry out the tasks. Why refers to the objective of the work activities; this should be included in the job summary and in each task description.

An excellent guide for the writing style of job descriptions is offered by The Revised Handbook for Analyzing Jobs.23 These include a terse, direct style; present tense; an active verb beginning each task description and the summary statement; an objective for each task, and no unnecessary or fuzzy words. The handbook also suggests how the basic task statement should be structured: (1) present-tense active verb, (2) immediate object of the verb, (3) infinitive phrase showing the objective. An example would be: (1) collects, (2) credit information, (3) to determine credit rating.

Unfortunately, many words have more than one meaning. Perhaps the easiest way to promote accurate job description writing is to select only active verbs that permit the reader to see someone actually doing something.

Sections of Job Descriptions

Conventional job descriptions typically include three broad categories of information:

- identification,

- work performed, and

- performance requirements.

The identification section distinguishes the job under study from other jobs. Obviously, industry and company size are needed to describe the organization, and a job title is actually used to identify the job. The number of incumbents is useful, as well as a job number if such a system is used.

The work-performed section usually begins with a job summary that describes the purpose and content of the job. The summary is followed by an orderly series of paragraphs that describe each of the tasks. Job analysts tend to write the summary statement after completing the work-performed section. They find that the flag statements for the various tasks provide much of the material for the summary statement.

The balance of the work-performed section presents from three to eight tasks in chronological order or in order of the time taken by the task. Each task is introduced by a flag statement that shows generally what is being done followed by a detailed account of what, how, and why it is done. Each task is followed by the percentage of total job time it requires.

The performance-requirements section sets out the worker attributes required by the job. This section is called the job specification. Job descriptions used for job evaluation may or may not include this section. An argument can be made that worker attributes must be inferred from work activities. This would require the job analyst to not only collect and analyze job information but also make judgments about job difficulty.

Managerial job descriptions

Managerial job descriptions differ from non-managerial job descriptions in what are called scope data. For example, financial and organizational data are used to locate managerial jobs in the hierarchy. The identification section of managerial job descriptions is usually more elaborate and may include the reporting level and the functions of jobs supervised directly and indirectly. The number of people directly and indirectly supervised may be included, as well as department budgets and payrolls. The work-performed section of managerial job descriptions, like that of non-managerial job descriptions, includes the major tasks, but gives special attention to organization objectives. Writers of managerial job descriptions need to remember that "is responsible for….." does not tell the reader what the manager does.

Careful writing is a requirement of good job descriptions. The words used should have only one possible connotation and must accurately describe what is being done. Terms should not only be specific but should also employ language that is as simple as possible.

Obviously, when job descriptions are written by different analysts, coordination and consistency are essential. These are usually provided by having some central agency edit the job descriptions.

For two examples of job descriptions, see Figures 10-5 and 10-6.

JOB TITLE: Sales Clerk

JOB SUMMARY: Serves customers, receives and straightens stock, and inspects dressing rooms.

TASKS

- Serves customers to make sales and to provide advice: Observes customers entering store, approaches them and asks to help, locates desired articles of clothing, and guides customers to dressing rooms. Decides when to approach customers and which articles of clothing to suggest. Sometimes gets suggestions from other sales clerks or supervisor. Rings up purchases on cash register and takes cash or check or processes credit card. Decides whether check or credit-card acceptance is within store policy. (80%)

- Receives and arranges stock to attractively exhibit merchandise: Unpacks boxes, counts items, and compares with purchase orders. Reports discrepancies to supervisor. Arranges and inspects new and old merchandise on racks and counters. Removes damaged goods and changes inventory figures. Decides where to place items in the store, within guidelines of supervisor. Twice a year helps with taking inventory by counting and recording merchandise. (15%)

- Inspects dressing rooms to keep them neat and discourage shoplifting: Walks through dressing area periodically, collecting clothing left or not desired. Remains alert to attempts to shoplift clothing from dressing area. Decides when security needs to be called in. Re-hangs merchandise on sales floor. (5%)

JOB TITLE: Branch Bank Manager

JOB SUMMARY: Promotes bank in community and supervises branch operations and lending activities.

TASKS

- Promotes bank services in the community to increase total assets of the bank: Engages in and keeps track of community activities, both commercial and social. Identifies potential customers in community. Analyzes potential customer needs and prospects, plans sales presentation, and meets with potential customers to persuade them to use bank services. (40%)

- Supervises branch operation to minimize cost of operation while providing maximum service: Plans work activity of the branch. Communicates instructions to subordinate supervisors. Observes branch activity. Discusses problems with employees and decides or helps employees decide course of action. Coordinates branch activities with main office. Performs personnel activities of hiring, evaluating, rewarding, training, and disciplining employees and financial activities of budgeting and reviewing financial reports. (35%)

- Evaluates and processes loan requests to increase revenues of the bank: Reviews and analyzes loan requests for risk. Seeks further information as appropriate. Approves (or denies) requests that fall within branch lending limits. Prepares reports to accompany other loan requests to bank loan committee. Keeps up with changes in bank lending policy, financial conditions, and community needs. (25%)

JOB ANALYSIS: DEAD OR ALIVE?

This chapter started by stating that job analysis is the first step in most Human Resource activities, and in particular, pay setting. Many would claim that job analysis is out-of-date because its use in old bureaucratic organizations does not make it appropriate for smaller, more nimble organizations. The reasons for this concern for job analysis are many:

- Jobs are changing in a way that makes them more fluid and flexible. Workers are required to do "what needs to be done" and not "what is in the job description."

- Job descriptions are becoming more generic and more like occupational descriptions.

- Job descriptions are broad so as to accommodate the growth of the individual on the job without requiring a whole series of promotions.

- Automation impacts job descriptions with the worker function changing to have more mental or non-observational activities.

- Technology is impacting job analysis by creating new ways to collect data and allowing for a higher level of analysis than in the past.

- There is a greater concern with the person aspects of job analysis, such as personality traits required for success or competencies and interpersonal relations24, than with the traditional work related topics.

- Teams are becoming more important to getting work done. This requires team members to do a range of activities within the team that are broader than what is typically contained in a job description.

Interestingly, much of the discussion of the demise of job analysis is really about the demise of the job analyst.25 The job analyst job is being incorporated into the role of the people who need to use information about jobs in order to accomplish their work. One of the signs of this is the use of new terms to cover the task of analyzing jobs, such a work analysis, work modeling and competency modeling.

SUMMARY

The first step in developing a salary structure based upon jobs is to collect information on jobs. This is the function of job analysis. The end product of this collection and analysis is a job description. This document becomes important not only for developing a salary structure but for almost all Human Resource functions.

Determine what information to include in job analysis or how to go about collecting such information. This chapter suggests that the information collected needs to focus on what the job is, how it is done, and why it is done. This approach suggests a focus on the activities of the worker as opposed to the worker's traits or the responsibilities the organization sees in the job.

Methods for collecting job information vary greatly from very informal to highly structured questionnaires. However, the most common method of collecting data is the interview. This leaves the data collection process flexible but subject to great variation. The use of computers increases standardization of the data collection process.

Footnotes

1 Brannick, M.T. and Levine, E.L., Job Analysis: Methods, Research and Applications for Human Resource Management in the New Millennium, Thousand Oaks, CA., Sage Publishers, 2002.

2 J. E. Zerga, "Job Analysis: A Resume and Bibliography," Journal of Applied Psychology, (1943), 249-67.

3 F. W. Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1911).

4 L. H. Gulick and L. Urwick, eds., Papers on the Science of Administration (New York: Institute of Public Administration, 1937).

5 U.S. Department of Labor, Handbook for Analyzing Jobs (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1991).

6 U.S. Employment Service, Dictionary of Occupational Titles (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1991).

7 Sackett, D.R., & Laczo, R.M. "Job and Work Analysis" in Borman, W.C., Kimoski, R.J. & Ilgen, D.R. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology Vol.12, New York, John Wiley, 2004.

8 Fine, S.A. and Cronshaw, S.F., Functional Job Analysis: A Foundation for Human Resource Management, Mahwah, N.J. Lawrence Erlbaum, Publishers, 1999.

9 McCormick, E. Job Analysis, New York, American Management Association, 1979.

10 H. Risher, "Job Analysis: A Management Perspective," Employee Relations Law Journal, Spring 1979, pp. 535-51.

11 K. Perlman, "Job Families: A Review and Discussion of Their Implications for Personnel Selection," Psychological Bulletin (1980), 1-28.

12 E. J. Cornelius 111, T. J. Carron, and M. N. Collins, "Job Analysis Models and Job Classification," Personnel Psychology (1979), 693-708.

13 Hartley, D.E., "Job Analysis at the Speed of Reality," Training and Development, September 2004, pp. 20-22.

15 J. J. Jones, Jr., and T. A. DeCottis, "Job Analysis: National Survey Findings," Personnel Journal (1969), 805-9.

16 E. J. McCormick, Job Analysis, (New York: American Management Association, 1979).

17 McCormick, Jeanneret, & Mecham , Op Cit.

18 McCormick, E.J., & Jeanneret, P.R., "Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ)", in Gale, S., Ed. The Job Analysis Handbook for Business, Industry and Government, Vol.2., New York, John Wiley, 1988.

19 Fine, S.A. & Getkate, M., Benchmark Tasks for Job Analysis, Lawrence Erlbaum, Publishers, Mahwah, N.J. 1995.

21 R. E. Christal and J. J. Weissmuller, New Comprehensive Occupational Data Analysis Programs (CODAP) for Analyzing Task Factor Information, Interim Professional Paper no. TR76-3, Air Force Human Resources Laboratory (Lackland Air Force Base, Lackland, Texas, 1976).

22 Peterson, N.G., Jeanneret, P.R., Mumford, M.D. & Borman, W.C. Occupational Information System for the 21st Century, 1999.

23 US Department of Labor, The Revised Handbook for Analyzing Jobs, Indianapolis, Ind., Jist Publishing Co. 1991.

24 Lucia, A.D. & Lepsinger, R. The Art and Science of Competency Models: Pinpointing Success Factors in Organizations, San Francisco, Jossey Bass/Pfeiffer, 1999.

25 "The Future of Salary Administration," Compensation and Benefits Review, July/August, 2001, p.10.

Internet Based Benefits & Compensation Administration

Thomas J. Atchison

David W. Belcher

David J. Thomsen

ERI Economic Research Institute

Copyright © 2000 -

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

HF5549.5.C67B45 1987 658.3'2 86-25494 ISBN 0-13-154790-9

Previously published under the title of Wage and Salary Administration.

The framework for this text was originally copyrighted in 1987, 1974, 1962, and 1955 by Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights were acquired by ERI in 2000 via reverted rights from the Belcher Scholarship Foundation and Thomas Atchison.

All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced for sale, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from ERI Economic Research Institute. Students may download and print chapters, graphs, and case studies from this text via an Internet browser for their personal use.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 0-13-154790-9 01

The ERI Distance Learning Center is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: www.learningmarket.org.